What's the saying? We can't see the forest for the trees? In the case of Oakmont Country Club, which June 16-19 hosts a record ninth U.S. Open, we can't see the forest for the lack of trees. The last time the Open visited Oakmont, in 2007, when Angel Cabrera won by a stroke—Tiger Woods missed a 25-foot birdie putt on the final hole, and Jim Furyk bogeyed the 17th after trying to drive the short par 4—the course had been so clear-cut that we proclaimed Mighty Oakmont had returned to its roots. "Its one-of-a-kind character has been reclaimed, restored and revitalized by astonishing tree removal," we wrote. "It's back to the barren look and brazen playing characteristics it had when it hosted its first U.S. Open, in 1927."

Back then we reported more than 5,000 trees had been removed along Oakmont's fairways, widening the panoramas and highlighting ferocious bunkering and deep drainage ditches that had previously been obscured beneath foliage. John Zimmers Jr., Oakmont's course superintendent, now confirms that crews actually removed about 7,000 trees before the 2007 Open. But here's a surprising footnote: Since 2007, Zimmers and his team have removed another 7,500 trees.

These days, from the veranda on Oakmont's clubhouse, one can see some portion of every hole, a view all the way to the flag of the hilltop third green at the far northeastern corner of the property. What's more, if you didn't know the Pennsylvania Turnpike existed—it separates holes 2 through 8 from the rest of the course—you wouldn't sense it from today's view. Because the turnpike is recessed, it's merely a horizontal shadow, barely noticeable. When dense rows of trees were on either side, they had emphasized its existence.

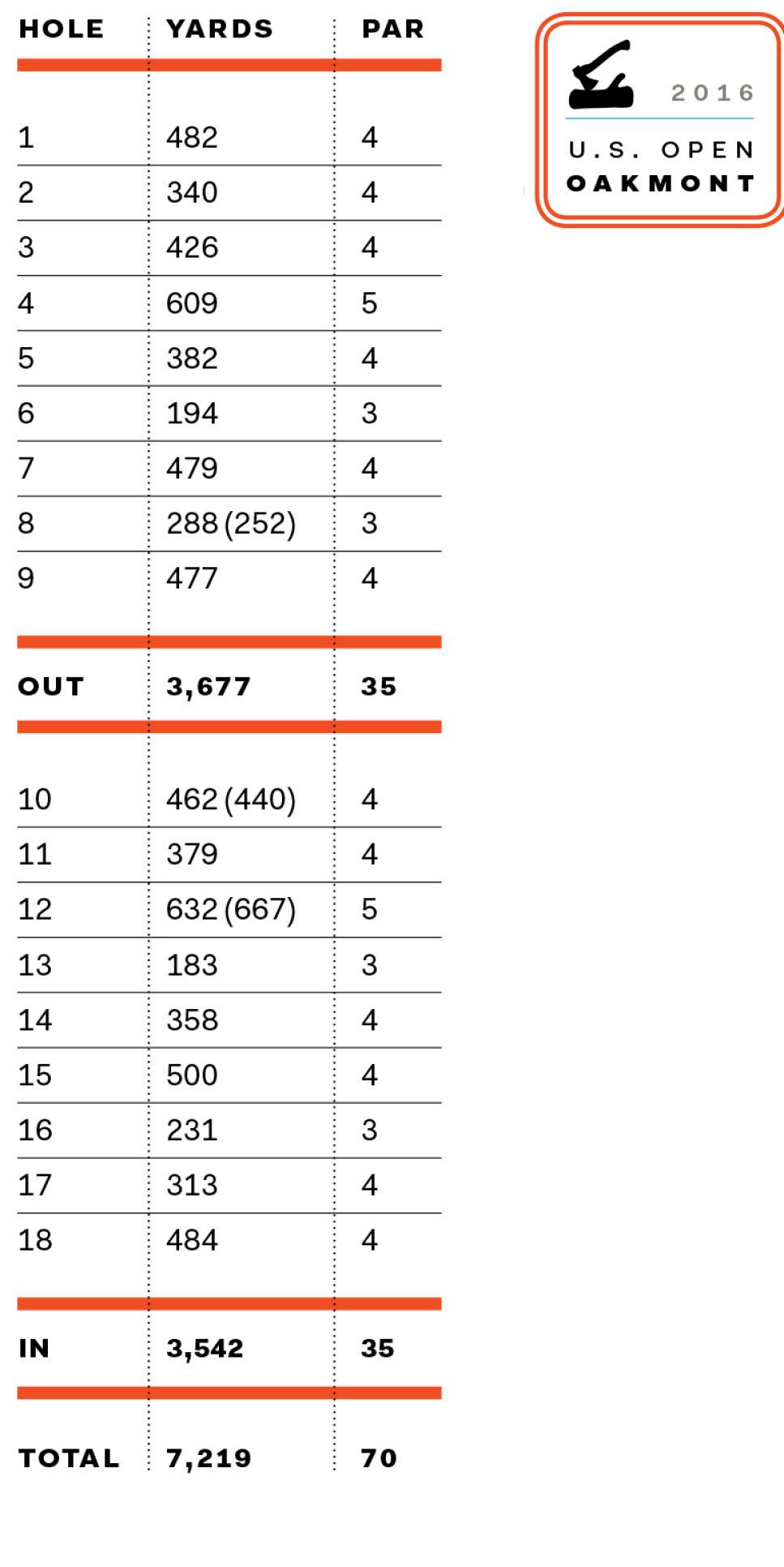

In the process of chain-sawing away 60 years of growth, Oakmont's dramatic topography has been fully revealed. Without a backdrop, the front-to-back slopes of the first, sixth and 10th greens are obvious. (For this year's Open, the back of the sixth green has been expanded, providing new pin placements, and at 12 two bunkers were removed and one was expanded. Those are the only major architectural changes to the course, which will play at par 70 and 7,219 yards, down 11 yards from 2007.) Elsewhere, hills look steeper and distances more deceiving. The downhill, par-5 12th now seems like it should be reachable in two even at 667 yards, though it's not the longest hole in U.S. Open history—the 16th at Olympic Club in San Francisco beats it by three yards.

WHEN OAKMONT LEADS, OTHERS FOLLOW

Why does this tree removal matter? Because Oakmont is the standard for American championship golf. Besides U.S. Opens, it has been the site of five U.S. Amateurs, three PGA Championships and two U.S. Women's Opens. Much of what happens at Oakmont affects the game. After all, it had fast greens decades before they became fashionable. Those swift greens caused the Stimpmeter to be created in the late 1930s, and whether that's a positive or negative, the Stimpmeter measurements of green speeds are here to stay at many, many clubs. For this year's Open, the United States Golf Association wants Oakmont's greens rolling at 14 feet on a Stimpmeter, the same speed they measured in 2007.

A near-universal high regard for Oakmont makes controversy acceptable. In 2007, the USGA played the par-3 eighth from a new back tee, stretching the hole to as much as 300 yards for the final round. (After acing the hole in a practice round at 288 yards, Trevor Immelman was asked if he saw the ball go into the hole and replied, "We couldn't see that far.")

At nearly any other club, a 300-yard par 3 would be considered a joke if not a travesty, but because it happened at Oakmont, a number of golf architects subsequently embraced the idea of an extremely long championship tee on a one-shot hole to require champion players to use a metal wood to reach the green. Oakmont gave architects cover to fight technology with an extreme measure.

The tree-removal program at Oakmont might well be this storied club's finest contribution to the game of golf. It reversed a trend it had helped start in the 1950s, the "beautification" of inland American courses by a sanctioned program of constant and misguided planting of trees funded by green committees and membership drives.

Thumb through Oakmont's tournament program from 1962—the year 22-year-old Jack Nicklaus won his first professional major, indeed his first professional tournament, in a playoff over Arnold Palmer—and what jumps out are aerial photos showing hole after hole dotted with saplings. Plus seven advertisements for tree nurseries. It's no wonder that the USGA subsequently selected Minnesota's Hazeltine National for the 1970 U.S. Open, despite cries that the eight-year-old course looked far too immature to host a national championship. Hazeltine at that time didn't look any younger than Oakmont. Hazeltine, site of the 2016 Ryder Cup Sept. 30-Oct. 2, now has towering hardwoods on many holes.

Oakmont was leafy green for U.S. Opens in 1973, 1983 and 1994, but then the club stopped planting trees and started removing them in bunches. Quietly, at first, and strictly to improve the health of turf normally blanketed in shade. Then-superintendent Mark Kuhns, with the approval of his 18-member green committee, had a crew assemble at 4 a.m. Under truck lights, they'd set down tarps, chop down a tree, cut it up, haul it off, grind the stump to ground level, vacuum up wood chips and leaves, then slap sod over it. By dawn, they'd be finished, and golfers playing the hole were none the wiser. Kuhns removed almost 500 trees that way until one day a caddie pointed out a gaping void to an influential club member.

It quickly became a contentious issue among the membership. There were meetings, threatened petitions and the specter of a lawsuit. Some called Kuhns "The Butcher of Oakmont" to his face. But the green-committee members doubled down, campaigning that Oakmont's trees should be removed because they were contrary to the original concept of founder H.C. Fownes. Among the evidence they presented: a 1938 Grantland Rice article, which referenced Oakmont as a links as famed as St. Andrews; a 1949 aerial of Oakmont showing scant trees; and a 1994 Golf Digest article critical of the prettification of the course ("Has the Old Bully Lost its Punch?" June 1994).

Eventually a majority of the members came around, but although they grudgingly allowed Kuhns to continue some tree removal, they refused to allocate additional funds. He had to squeeze the expenses from his normal operating budget, and as a result other areas of the course suffered a bit.

In late 1999, Kuhns moved to Baltusrol, site of this year's PGA Championship, and Zimmers took his place. He stepped up the tree removal, tying many expenses to club capital projects to cover costs. By 2002, the effects were so dramatic it warranted a follow-up story in Golf Digest ("Mission: Unpopular" October 2002). The story quoted Tom Meeks, then the USGA's senior director of rules and competition: "If any club thinks they would be hurting themselves by cutting down a few trees, go look at Oakmont and see what they've done. They are the leaders in the clubhouse."

AN EXAMPLE OF SUSTAINABILITY

For this year's Open, the USGA plans to highlight Oakmont's tree-removal program as another facet of sustainability. After all, instead of replacing the trees with lush, maintained turf that would demand additional water and chemicals, many areas of former forest are now covered in tall fescues that need little maintenance and turn bronze and wavy in later summer. (Trivia note: Though other bunkers at Oakmont are edged by a bluegrass-ryegrass mix of maintained rough, the huge Church Pews bunker between the third and fourth holes has each pew planted in unmaintained fescue, because the club believes the famed hazard deserved a distinctive look.)

Other grand American courses have removed pointless trees in the past decade and a half, and some were chopping and pruning even before Oakmont's extensive clear-cutting became public. But had Oakmont not succeeded in its effort in such a dramatic, visual manner, and had that effort not been well-received (finally) by its membership and those who study and promote golf-course architecture, it's doubtful that similar programs would have occurred at such prominent clubs as Olympic and Oak Hill. The nearly treeless Oakmont is an extreme example, a total reversal of the sentiment that trees belong on a golf course, because its heritage didn't rely on aerial hazards whatsoever. Other clubs are more content to retain some trees for safety or aesthetic purposes, which is fine. But the lesson of Oakmont is that every club should re-examine its landscape. Most would find many of their trees superfluous and, as at Oakmont, the character of their layouts would improve once those trees are removed.

TELEVISION (EDT)

June 16, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. (FS1), 5-8 p.m. (Fox)

June 17, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. (FS1), 5-8 p.m. (Fox)

June 18, 11 a.m.-7 p.m. (Fox)

June 19, 11 a.m.-7:30 p.m. (Fox)

TALE OF THE TAPE

2007 U.S. OPEN TOP FINISHES

• Angel Cabrera: 69-71-76-69—285 (+5)

• Jim Furyk: 71-75-70-70—286 (+6)

• Tiger Woods71-74-69-72—286 (+6)

• Niclas Fasth: 71-71-75-70—287 (+7)

• David Toms: 72-72-73-72—289 (+9)

• Bubba Watson: 70-71-74-74—289 (+9)

• Nick Dougherty: 68-77-74-71—290 (+10)

• Scott Verplank: 73-71-74-72—290 (+10)

• Jerry Kelly: 74-71-73-72—290 (+10)

• Justin Rose: 71-71-73-76—291 (+11)

• Stephen Ames: 73-69-73-76—291 (+11)

• Paul Casey: 77-66-72-76—291 (+11)

OTHER SELECTED FINISHES

• Brandt Snedeker: 71-73-77-74—295 (+15)

• Ian Poulter: 72-77-72-77—298 (+18)

• Zach Johnson: 76-74-76-74—300 (+20)

• Ernie Els: 73-76-74-78—301 (+21)

• Jason Dufner: 71-75-79-80—305 (+25)

AMONG THOSE MISSING THE CUT

• Phil Mickelson (74-77)

• Sergio Garcia (79-75)

• Henrik Stenson (79-76)

LEADERS BY ROUNDS

• Round 1, Nick Dougherty, -2

• Round 2, Angel Cabrera, E

• Round 3, Aaron Baddeley, +2

• Round 4, Cabrera, +5

ROUNDS IN THE 80S

• Aaron Baddeley led Tiger Woods by two strokes entering the final round but triple-bogeyed the first hole and finished T-13 after an 80, one of 60 rounds in the 80s in 2007. The breakdown in scoring: 80 (17 times), 81 (15), 82 (8), 83 (6), 84 (5), 85 (4), 86 (3), 87 (1), 89 (1).

2007 SCORING STATS

The field scoring average was 75.72. Tour pros tend to beat up par 5s, but the 609-yard fourth (5.06) and the 667-yard 12th (5.41) both played over par. The easiest hole was the 358-yard 14th (4.05), and the hardest was the 484-yard 18th (4.60).

2007 STAT LEADERS

Driving distance, George McNeill, 311.4 yards; fairways hit, Fred Funk, 41; greens in regulation, Tiger Woods, 49; putts, Niclas Fasth, 114; birdies, Geoff Ogilvy, 14; bogeys, McNeill, 26; double bogeys/others, Jason Dufner, 8/0.

OAKMONT'S OTHER U.S. OPENS

1994: After finishing at five-under-par 279, Ernie Els won a 20-hole playoff. Els and Loren Roberts shot 74s to eliminate Colin Montgomerie (78) before Els' birdie on the second hole of sudden death.

1983: Larry Nelson holed a 62-foot putt after play resumed Monday morning and won at four-under 280.

1973: Johnny Miller's final-round 63 put his winning total at five-under 279

1962: Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer finished at one-under 283 before Nicklaus won the playoff, 71-74.

1953: Ben Hogan won $5,000 with a total of five-under 283.

1935: Sam Parks Jr. won at 11-over 299.

1927: Tommy Armour and Harry Cooper tied at 13-over 301 before Armour won the playoff, 76-79.

OAKMONT'S U.S. WOMEN'S OPENS

2010: Paula Creamer shot a final-round 69 to win by four strokes at three-under 281.

1992: Patty Sheehan and Juli Inkster tied at four-under 280 before Sheehan won the playoff, 72-74.

OAKMONT'S U.S. AMATEURS

2003: Australia's Nick Flanagan beat Casey Wittenberg on the 37th hole.

1969: Steve Melnyk won by five strokes in stroke play (286).

1938: Willie Turnesa beat B. Patrick Abbott, 8&7.

1925: Bobby Jones beat Watts Gunn, 8&7.

1919: S. Davidson Herron defeated Jones, 5&4.

OAKMONT'S PGA CHAMPIONSHIPS

1978: After tying Jerry Pate and Tom Watson at eight-under 274, John Mahaffey won with a birdie on the second playoff hole.

1951: Sam Snead beat Walter Burkemo, 7&6.

1922: Gene Sarazen beat Emmet French, 4&3.

FUTURE U.S. OPEN VENUES

2017: Erin (Wis.) Hills

2018: Shinnecock Hills G.C. / Southampton, N.Y.

2019: Pebble Beach G. Links

2020: Winged Foot G.C. / Mamaroneck, N.Y.

2021: Torrey Pines G. Cse. (South) / La Jolla, Calif.

2022: The Country Club / Brookline, Mass.

2023: Los Angeles Country Club (North)

2024: Pinehurst (N.C.) Resort & C.C.

Course Tour: A hole-by-hole-look at Oakmont C.C. >>

Video flyovers: Take an interactive tour of Oakmont C.C. >>