News

Checks and Balances

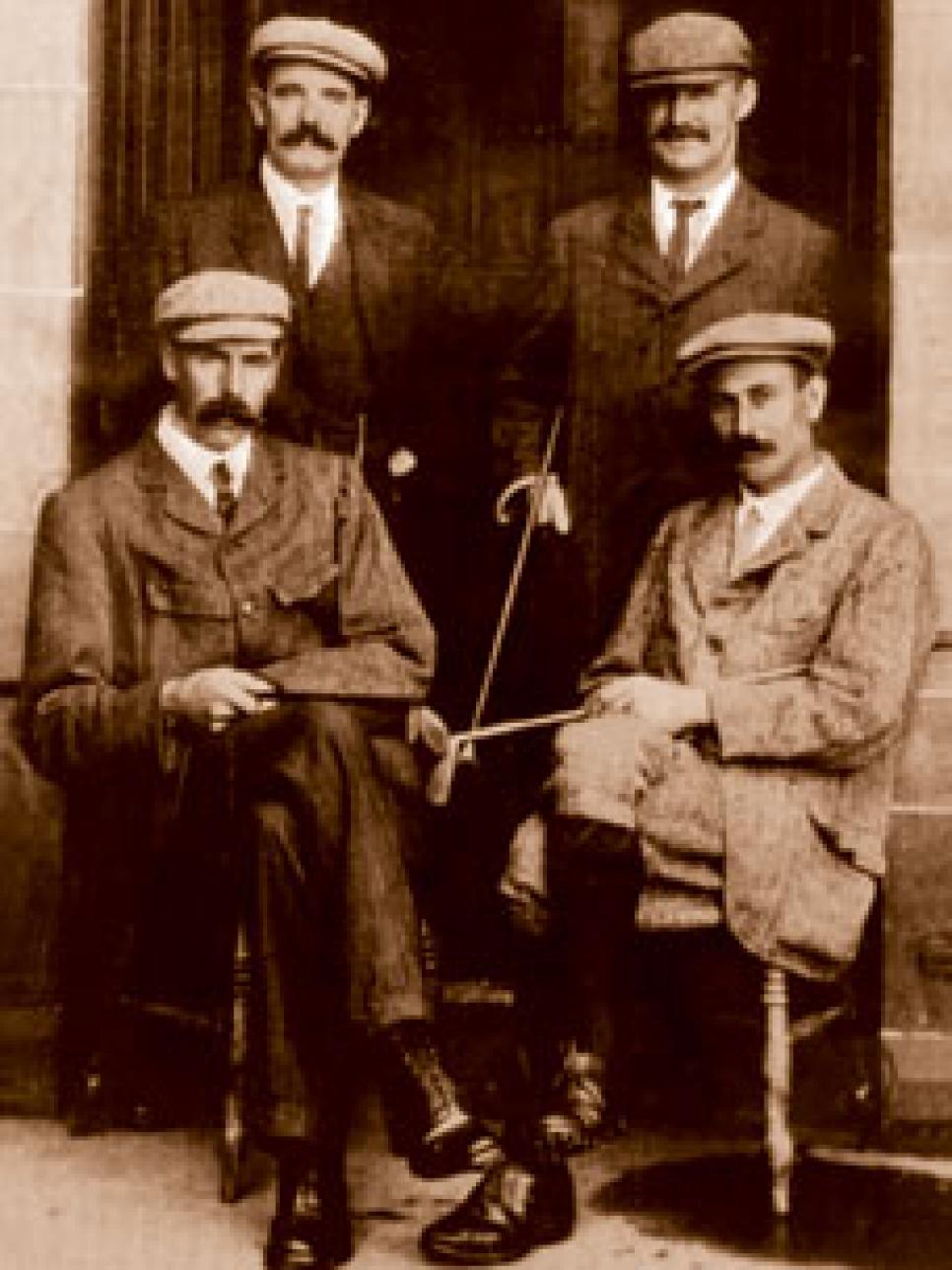

Herd (top left) utilized the new Haskell ball to win the 1902 British Open over Vardon (lower right). J.H. Taylor (top right) and James Braid complete this 1905 photo.

Hale Irwin was at a charity outing recently that included a number of current PGA Tour members, golfers who weren't even born in 1974 when he won the first of his three U.S. Open titles. At 64, Irwin already knew that trying to describe to this generation of golfers what it was like to play with the balls and clubs of his prime can come off like a "When I was a kid, I had to walk in the snow for a mile to get to school" kind of sermon.

But he got a gentle reminder nonetheless when giving his take on Jack Nicklaus' excellence using the gear of yesteryear.

"I told 'em you guys all hit it long -- you don't have to throttle back -- but you would learn if the ball you used curved," Irwin says. "It was a friendly discussion, but they looked at me like I was a triceratops. They have no clue what I'm talking about."

The grooves rollback for 2010 might provide a glimpse to today's elite players of the world in which Irwin and his contemporaries plied their trade decades ago and force them to tweak their strategy. Placed in the evolutionary timeline of equipment advances and rules modifications that have affected golf over roughly the past century, however, the new groove rule seems more of a blip than a sea change despite being one of the rare instances when something has been "taken away" from a golfer's equipment arsenal by a governing body.

"A wedge from the rough is still a wedge from the rough," contends Irwin, who has 65 combined victories on the PGA and Champions tours. "You can still hit it high and drop it straight down."

While flyers could prove more problematic, especially for younger players so accustomed to the bite that the outlawed grooves have routinely provided, one thing is certain: From the time, more than a century ago, when Coburn Haskell balled up some rubber bands and saw how lively the improvised sphere bounced, to the NASA-like research-and-development labs that mark modern equipment innovation, inventive minds have looked for a better way.

In turn, the best golfers (who occasionally were also the ones designing the better tools) have adopted technology in an attempt to play better, and even adapted their games to suit improvements in balls and implements. These proclivities go back a long time, along with the accompanying debates about whether "progress" is good for the game.

Consider Walter J. Travis, the late-blooming star of around the turn of the 20th century, who won three U.S. Amateurs and, in 1904, became the first American to win the British Amateur. Travis was an effective early user of the wound ball and his success with the unusual center-shafted Schenectady putter prompted a ban of the model by the R&A that lasted 41 years. Moreover, he sought increased distance in a manner some might think is only part of the modern quest to hit the ball farther.

As Bob Labbance points out in The Old Man, his 2000 biography of Travis, the golfer employed, as early as 1905, a driver with a 50-inch hickory shaft, seven inches longer than the period's standard. Travis' novel approach to longer tee shots was the talk of the sport more than 80 years before players such as the senior tour's Rocky Thompson put a driver with a 56-inch graphite shaft in his bag.

"He claimed that by simply standing further from the ball, shortening his backswing and exaggerating his follow-through," Labbance writes of Travis, "he could swing the long-shafted clubs and gain 10 yards on each drive," but he acknowledged that the extra power cost him some accuracy. Still, Travis was an influential figure, and stars Willie Anderson and Alex Smith were among the converts to elongated drivers in 1905.

Travis, of course, wasn't the only golfer who took advantage of the wound rubber-core ball that supplanted the solid gutta perchas. Harry Vardon clung to the worth of the old-style ball, winning the 1900 U.S. Open with the "Vardon Flyer" he was promoting for Spalding. Two years later at the British Open at Hoylake, though, Vardon was beaten by Sandy Herd, one of the minority of contestants who played a Haskell. Herd had criticized the new technology prior to the Open, according to John Stuart Martin's The Curious History of the Golf Ball, but "scrounged" one wound ball from eight-time British Amateur champion John Ball and used it the entire 72 holes.

Golf ball innovation went unchecked until 1921, when a maximum weight of 1.62 ounces and minimum diameter of 1.62 inches was established. The rubber-core models, called "Bounding Billies" because of their zip, alarmed many who feared -- in a prelude to more recent concerns about how far the ball traveled -- the challenge was being removed from the game because the new designs soared as many as 60 yards farther than the guttie.

As of Jan. 1, 1931, the USGA veered away from the R&A and mandated that a ball had to be a minimum of 1.68 inches and could weigh no more than 1.55 ounces -- slowing it down and making it more susceptible to the wind. Traditionalists such as architect Donald Ross loved the rollback. "The new standard golf ball has eliminated from the top-notch ranks the mechanical golfer of the past and the skilled shotmaker will now reap his deserved reward," Ross noted in the Boston Herald. "The game was becoming too stereotyped with the old ball. [It] did not place enough of a premium on a well-hit shot. The sluggers were getting such distances off the tee that they had nothing but easy pitches for the second shots."

Photo: USGA; AP PHOTO/JOHN LINDSAY

Ballmakers tried to make the best of the situation, and turn it into a marketing opportunity. "Off the tee, it cracks like a rifle," Gene Sarazen boasted for Wilson in a pitch for the company's downsized Hol-Hi ball. But the new size was roundly ridiculed. Life magazine urged golfers to write the USGA to demand a change: "Balloon ball, this plaything of the wind, this ping pong pellet that flies like a kite and putts like a tumble bug." Jesse Guilford, one of the long drivers of the day, said simply that the ball was "larger, lighter and lousier."

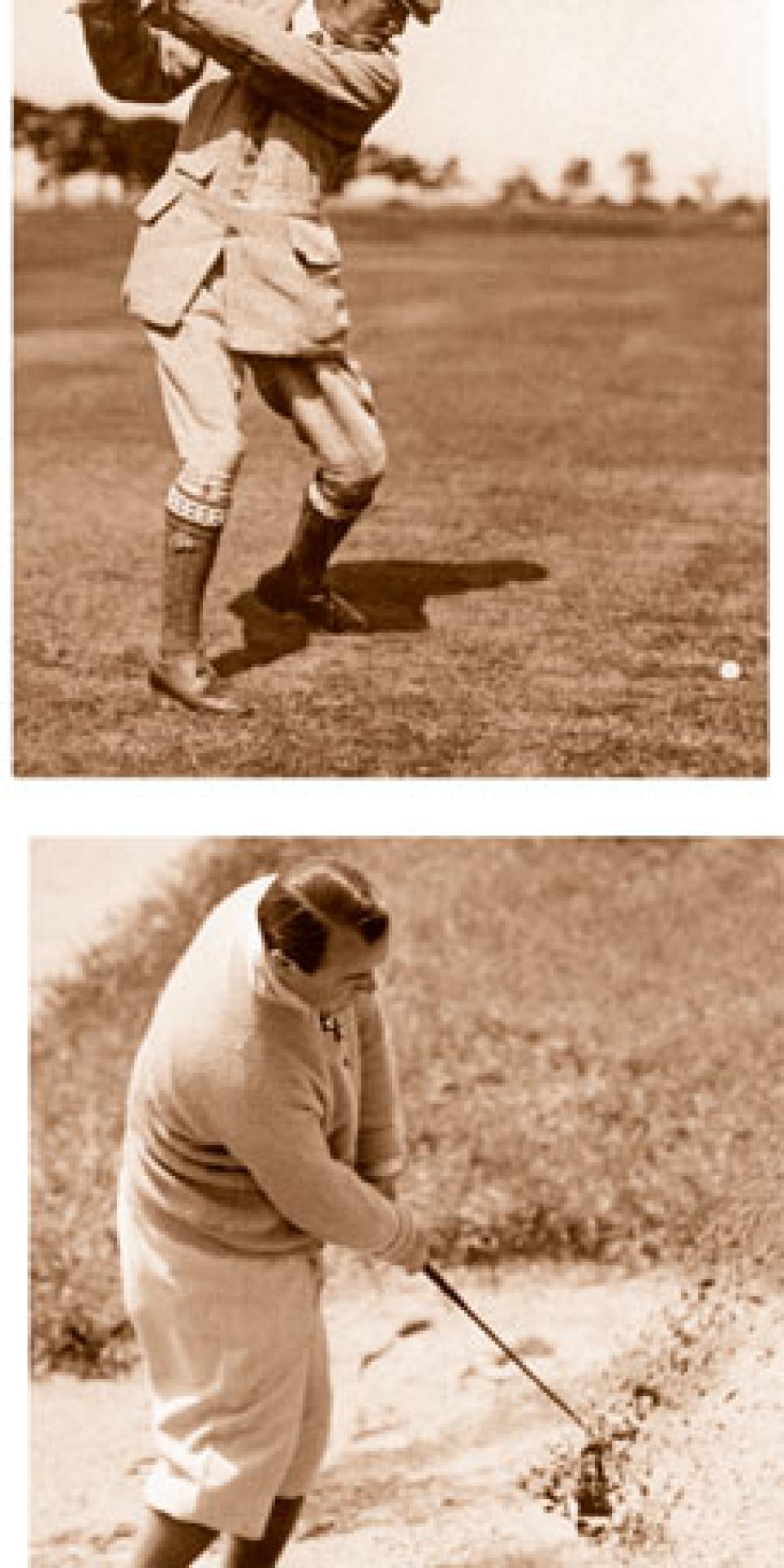

Glenna Collett Vare, the best American woman golfer, supported the ball at first but later said "that in the wind the 'balloon ball' did cut some queer capers." Partly because of the squawking, the balloon ball was dead after just a year, replaced in America with a 1.68-inch, 1.62-ounce standard, with the rest of the world having a 1.62-inch, 1.62-ounce stipulation until 1990 (the R&A required use of the "American ball" in the British Open starting in 1974). Meanwhile, it was a busy time on other equipment fronts. Steel shafts became legal in the U.S. in 1924 and under R&A rules in 1929, although much of the early steel was painted tan to mimic the traditional hickory.

Billy Burke, in 1931, was the first U.S. Open champion to use steel rather than hickory shafts, but oddly this milestone didn't get much attention at the time, The American Golfer failing to mention it in the magazine's extensive coverage of that year's Open. Others took care to notice the development, however.

Foremost was a young pro from Texas named Byron Nelson, who rebuilt his swing -- and created a prototype for the modern action -- because of steel shafts. "I get credit for that because I started using the feet and legs to get more freedom down below," Nelson reflected to writer Nick Seitz many years later. "Before, with hickory shafts, you had to roll the club open on the backswing, then roll it closed on the downswing and hit against a stiff leg. It was hard to be consistent. So I started using my lower body more to keep the clubface square."

Until 1938, when a 14-club maximum rule was instituted, there were a lot of clubfaces in pros' bags. While champions of a generation earlier, such as 1908 U.S. Open victor Freddie McLeod, carried as few as seven clubs, caddies in the 1920s and 1930s sometimes were loaded down with bags bulging with more than 25 clubs. Lawson Little and Harry Cooper carried as many as 26 clubs, while others such as Paul Runyan used 18 or 19.

One reason for the large assortment was the advent of the wedge (Little carried seven). Jock Hutchison won the 1921 British Open using lofted clubs with deep slots on their faces. The R&A quickly banned the faces, and the USGA soon followed. Sand shots remained dicey business, even for the best. Players had to chip the ball out of bunkers -- a style favored by Walter Hagen -- or improvise an explosion with the niblick.

Photo: USGA; AP PHOTO/JOHN LINDSAY

McLeod, who stood just 5-foot-4 and weighed only 118 pounds, was a master of the "cut" sand shot. He would strike the sand just far enough behind the ball so that there was the tiniest cushion of sand between the face and the ball that helped impart spin. The shot chewed up balls, but was effective. As The American Golfer noted in 1931: "That ball comes out of there like a bullet from a gun, spins like a top around in a sweeping motion and usually leaves him with a short putt for the hole."

But it was a risky shot, and even McLeod bladed his share. One blunder forced Bobby Jones to duck to avoid getting hit during a practice round at a British Open. Players kept looking for a simpler way out of sand. Horton Smith, who would win the first Masters in 1934, discovered one early in 1930 on a visit to Houston CC. A man named E.K. McClain was using what Smith later termed a "freak niblick," a 23-ounce weapon with a hickory shaft, concave face, rounded flange sole and heavy weight at the top of the blade fashioned by a blacksmith.

Smith was good friends with Bobby Jones, who liked the club so much Smith asked McClain to get one crafted for Jones. In the final round of his winning effort at the 1930 British Open at Hoylake, it proved pivotal for Jones, who used it to hit a great shot from an awkward lie in a bunker on the 16th hole. Smith contracted with the Hagen company to mass-produce the club, and the club sold like crazy (more than 300 wedges) in the Merion GC golf shop the week Jones completed the historic Grand Slam.

But the game's ruling bodies didn't like the looks of the freak niblick, and outlawed it because of the concave design as of Jan. 1, 1931. The evoution of the wedge continued in early 1932 when Sarazen began to tinker on a design without a concave face but that still utilized the heavy flange crucial to the McClain/Smith creation. Soldering metal onto Wilson sharp-edge pitching wedges, Sarazen improvised clubs that would more easily bounce through the sand rather than digging in. This allowed an explosion of sand to safely lift the ball out of trouble.

Sarazen won the 1932 U.S. Open in record style then captured the British Open as well, where he had his caddie put the sand wedge in the bag upside down so his invention would be kept under wraps even though his profiency from sand was key to his win. "I prefer to take no chances, and I have spent more hours than I am willing to confess in practicing this shot, so that now a bunker has no terrors for me," Sarazen later explained. "There are times when the ball can be chipped out cleanly, but this is a very delicate and difficult shot and calls for the most expert execution."

Not every pro got as good from bunkers as Sarazen, but the explosion shot revolutionized recoveries. About 50 years later, another compactly built pro with a good short game, Tom Kite, started another trend on tour: the use of a third wedge with a loft of about 60 degrees. While nearly every elite golfer carries at least three wedges now, no one did it routinely until Kite began doing so in the second half of the 1980 PGA Tour season upon the urging of short-game guru Dave Pelz.

"I kept records of where I hit shots for about a six-month period starting in 1980," Kite recalled to Golf Digest in 1993. "After that six-month period, I decided Dave's recommendations were accurate, and that I could have a better short game by putting a third wedge in there all the time. That's when I really became a good player. [Lee] Trevino had done it occasionally, and I am sure some other players had done it occasionally, but nobody had done it 100 percent of the time prior to me. … I wish everybody had not copied me, though."

Not everyone did -- not immediately anyway. Curtis Strange won consecutive U.S. Opens in 1988-89 without a third wedge. Loren Roberts also didn't use one until the last couple of years on the Champions Tour after a traumatic experiment in the mid-1980s. "I got one and took it out to show my teacher, Jim Swaggerty," Roberts remembers. "I bladed the first couple then fatted a few. He said, 'Let me see that thing.' I handed it to him, and he broke it over his knee and said, 'Son, your name is on your bag. You ought to be able to hit every shot with one sand wedge.' That's why I never had one until a couple of years ago."

Irwin, too, didn't use an L-wedge until 2005 when he finally switched out his trusty 2-iron (with which he had trouble achieving enough carry with lower-spinning, solid-core balls). The 1970s seem like a long time ago. "We carried the [measuring] ring," Irwin says. "Of a dozen balls, the ones that slipped through like a marble, those were the ones we used on the long holes. The ones that just fit through, you used them on shorter holes. And the ones that were like eggs, you put them in your practice bag. As for changing the loft and lie of your clubs, if it wasn't at the factory, you did it on the nearest tree root. You beat on it until it looked right, then you'd go play. Everybody played by feel."

Not that science wasn't making inroads. Until the "one-ball" condition of competition was established in 1979, some tour pros switched from balata models to harder Surlyn-covered two-piece balls on long par 3s or holes into the wind.

Photo: USGA; AP PHOTO/JOHN LINDSAY

"Everybody had started to figure out more about equipment," says Jerry Pate. "In the 1975 Walker Cup at St. Andrews, [a manufacturer] made up small-dimpled balls for the American team. Those balls were so hot you can't imagine. We were outdriving the Brits 40 or 50 yards with these no-velocity restriction balls. That's when I first realized the ball companies can do whatever they want if they put their mind to it."

Other technology also creeped into the game. Pate, who won the 1976 U.S. Open when he was 22, was loyal to a persimmon-headed driver with an aluminum insert. "[Master clubmaker] Toney Penna saw me at the 1975 Masters and said, 'Son, if you'll keep driving with that metal face, you're going to hit it straighter and farther than anybody on tour of a similar stature,' " Pate says. "My club had just enough bulge, and I'd filed the grooves totally off. The aluminum insert would spit the ball out there, lower and flatter. My senior year in college, guys named my driver, 'Knuckle.' I remember playing with Arnie and Jack early in my career and outdriving them. They'd get mad. I'd say, 'It was the aluminum insert, guys.' "

Tour players today, of course, utilize metal-headed drivers with clubheads about three times as large, shafts about half as heavy and a couple of inches longer. Kids have L-wedges in their first junior sets and grow up hitting solid-core, multilayer balls that are uniformly round and lively with swings they dissect on high-tech video.

"First time I ever saw my swing, I was playing in a little tournament on a muny course in Colorado Springs," Irwin says. "The evening TV sports came on and showed me hitting my second shot to the last hole to win the tournament. I was shocked at what my swing looked like, versus what I thought it was."

If nothing else, maybe the new grooves will bring back a touch of the old mystery.