News

The Prince Of Dirt

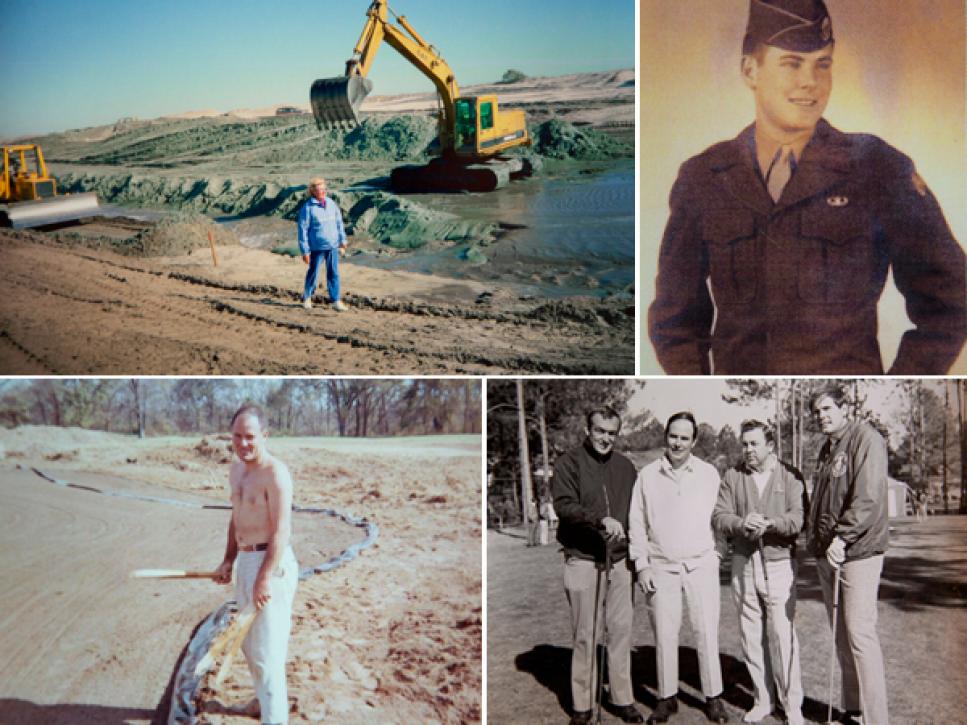

Pete Dye at Gulf Stream's redesigned 18th.

Whoooooooooa, Nellie . . .

In the vortex of adventures that nothing adequately prepares you for -- take skydiving, for instance, or the luge -- riding shotgun in a golf cart with Pete Dye at the helm the day after his 88th birthday has its place. Trust me on this. He finds humps. He finds bumps. He finds swales. He skirts the edge of the Atlantic. He angles toward the drains; oh, how Pete dies for his drains. He waves to the paying customers on the fairways. On this crisp afternoon in late December, they naturally wave back.

Welcome to Gulf Stream GC -- between the ocean and the canal in Delray Beach, Fla. -- a place where everybody knows Pete Dye.

Of course, folks know Pete Dye, the game's most singular crafter of courses, wherever golf is played. But at Gulf Stream it's different. It's not one of the klieg-light affairs -- like TPC Sawgrass' Players Stadium Course -- that have accumulated 32 Players Championships with a 33rd on tap this month; five PGA Championships (Whistling Straits, the Ocean Course at Kiawah, Crooked Stick, Oak Tree); 24 USGA championships (including Harbour Town, Blackwolf Run, The Honors Course, Long Cove); five LPGA Championships (Bulle Rock); a Ryder Cup; a Solheim Cup and more hair ripped from the pates -- including Jerry's -- of more golfers than even Watson -- the computer, not Bubba or Tom -- can readily cipher. For Dye, this is home, a decidedly under-the-radar and relatively kind 18 designed by Donald Ross in the 1920s. "He made one trip and laid it out and had some other guy build it," Dye declaims incredulously. "He didn't spend time building courses."

Dye does.

It's his hallmark. Spending time. Discovering. Rediscovering. Planning on-site. Sculpting freely in the dirt. Pass after pass, that's where he finds the little things -- the contours, the slopes, the zigs and the zags -- that have been driving golfers crazy for half a century. In Dye's complex and creative mind, that is where courses are minted: in the dirt, not on paper. Good thing, too, because he's not much with a pencil. "Hell," he growls, "my dog can draw better than me."

Amazingly, it's taken Dye years to get his fingertips into this exclusive patch of Florida's Gold Coast, and he's made what Ross left at Gulf Stream even gentler. Longer, yes -- the 21st century, to his chagrin, has its demands -- but the greens and approaches are far more receptive, and there is even a beloved ocean view. Overall, the course plays, well, friendlier.

Wait a second: Pete Dye? Friendlier? The Pete Dye famously on record with, "Golf is not a fair game, so why should I build a fair golf course?"

Uh-huh. But let him explain. "I live here," he says, his eyes dancing. "They know where to find me."

Pete and Alice, his wife and partner on and off the course for more than six decades, have been members at Gulf Stream some 30 years. "They took her in," he shrugs, both hands on the wheel. "They had to take me too, I guess." The club is so close to their winter front door -- in summer they're still back home in Indiana -- that Dye's cart is his prime conveyance from his driveway to his secret entrance behind the second tee.

Now to those drains. "You see," as we skirt another, "I knew this course was underwater, but I didn't give a damn, 'cause nobody ever asked me about anything. I've been on the green committee here forever" -- imagine, Pete Dye on your green committee! -- "but you know green committees. You try to tell them something, and they go like this." He mimes a pair of ships passing. So, he simply sat mum -- until they asked. They had a plan too. "But I didn't listen to anything." After all, they couldn't fire him; he wasn't getting paid. "I just do this for the hell of it. The place was a mess."

So, on we go, up one fairway, down the next, his renovation virtually done, the color commentary flying. "There," Dye points to a new bunker, "I don't know why I did that. I just know it makes it OK." And there, where a stand of trees once stood, "I took out a million of 'em. They almost came after me with an ax;" and there, alongside the eighth, "This used to be the worst hole in the world;" and, there, at a distaff foursome circling their putts, "They could buy the New York state bank." Reversing direction again, his mind, like his cart, keeps throttling past the acceptable speed limit until the former hits a roadblock and the latter hits the brakes.

Why, I've just asked him, is he still at it? Why, when most his age are content to put up their feet, is he still caking his with dirt and dust? (Just check out his shoes.) Why is he still flying off for days at a time to oversee renovations in Georgia and South Carolina and Virginia and Indiana, not to mention his own backyard, in the past year? Why is he wrestling with ideas for a new 18 through challenging gunk and forest north of Jacksonville (and, as 2014 progressed, a potential fifth course for patron Herb Kohler -- "Every time I spend a dollar, he has a heart attack" -- near Whistling Straits in Wisconsin)? What's left to prove?

The silence is eerie.

Then: "I don't know," he returns with a shake of the head. "I've got to be crazy."

As in: still crazy after all these years about what he does. "I just like to build," he says. "It's a big puzzle."

As adventures go, then, there's nothing remotely like this in golf, because there's nothing like being held captivated by that most wondrous of all human creations: a true visionary expounding on his vision with a chunk of that vision surrounding him.

That Dye is one of the most extraordinary architects in the game's history, one of only four in the World Golf Hall of Fame, on par with Macdonald, MacKenzie, Ross or any other name pulled from the pantheon, isn't news. Nor is his knack for drilling deep into the dark recesses of the golf mind to whip up the most visually intimidating, nail-biting, knee-knocking tests of the game anywhere. Who else shoulders such colorful appellations -- from Dye-abolical to the Marquis de Sod? Who else has mentored so many burgeoning designers under his expansive wing -- think, for starters, Bill Coore, Bobby Weed, Tom Doak and Jim Urbina -- that there is even a pun for that: the Dye-ciples, who have evolved into an important hands-on force spawned by Pete's preference for slow-cooking courses one at a time. "Pete never talks about designing a golf course," says Doak. "He talks about building them." Adds Urbina: "He's the instruction manual."

But all of that hardly scrapes the façade off one of golf's true characters, a rare man whose character is as artful as the masterpieces he has coaxed -- and bulldozed, with himself at the controls -- from swamps (Sawgrass) and deserts (PGA West) and the edges of cliffs (Teeth of the Dog in the Dominican Republic). "Whatever cloth they cut Pete from," assures Coore, "you can rest assured that was the one and only piece they had. I've never met anyone like him."

Who has?

As Coore says, "Nobody else has ever changed the direction of golf architecture twice."

Here's another adventure for which there is no proper preparation: A casual sit-down with Dye, his dog beside him, in the Florida room overlooking his backyard to talk about golf and courses and his long romance with the game. The synapses snap. The sheer expanse of the conversation keeps you on edge; like in his cart, he takes so many twists and turns that you're breathless just listening. He's funny and he's puckish and there's no saccharine in his servings. He eschews rose-colored glasses; he sees clearly through lenses larger than some of the greens he's built. At 88 -- a Peanuts birthday balloon sits prominently beside the Christmas tree in the adjacent room -- Dye, a true lion in winter, may have lost a step or two in his gait and more than a few miles per hour from the swing that got him to six U.S. Amateurs, a British Amateur, and the 1957 U.S. Open (where he gleefully exhales that he tied Arnold Palmer and bettered Jack Nicklaus), but his aura and attitude? "He's the oldest teenager I know," says Weed. "He's the Energizer Bunny of golf."

At the moment the conversation is hopping around TPC Sawgrass, Dye's second great architectural swerve. The first came at Harbour Town, in the late 1960s, where, teamed with a rookie consultant named Nicklaus, he made a conscious decision to concoct an alternative in the South Carolina lowcountry to Robert Trent Jones. Short and strategic, Harbour Town was the anti-Jones incarnate, a revelation with its priority on finesse and its premium on ingenuity above power, the exact kind of golf the Dyes, superb shotmakers both, enjoyed playing and played so well. The greens were small. The fairways were wide, but deceptive. Railroad ties and cedar planks offered visual contrast … and something to think about; so did the stunning view to the sea and the lighthouse to highlight the heroic finish Dye would become synonymous with. The construction was so hands-on that Dye -- with Alice in her customary role as editor of his manuscript -- was still touching up the morning of its debut as the site of the first Heritage Golf Classic in 1969.

"Trent was the prime guy then," says Dye, and Dye was such a Jones devotee in his early days that he sought out Jones for a job, which he didn't get, and advice, which he did. "I copied everything he did," says Pete. "He became a good friend of mine. I was closer to him than his boys were. But he just built the same course everyplace he'd go. He was smarter than hell."

Like Jones' boys, Dye was also born into the game. His father Paul -- aka Pink -- coaxed a nine-hole course from family land in Urbana, Ohio, shortly before his son Paul -- aka Pete -- was born. As Pete grew into a hot young stick, Pink introduced him to such tour de forces as Scioto and Camargo, but the kid was far more interested in his play than the playing fields. "I recognized that some courses were better than others," he says, "but why they were didn't dawn on me."

Stationed at Fort Bragg, N.C., during World War II, Dye got to play nearby Pinehurst No. 2 a lot when he wasn't tending the sand-green course on the post. He got to meet Donald Ross. More meaningfully, Dye was fascinated by Ross' angles of play on No. 2 in a way he hadn't been about other designs he had seen.

By 1946, Dye was out of the Army, playing in his first U.S. Amateur, and attending Rollins College outside of Orlando, where he met Alice, a future two-time U.S. Senior Women's Amateur champion and qualifier for 12 U.S. Women's Opens. They married in 1950 and moved to her hometown of Indianapolis where he became a star insurance salesman. He's always been a salesman. "He has such charisma. He charms people," says Coore. "He treats everyone -- the people he works with and the people he works for -- the same. He gets them to believe in his vision."

Which hadn't yet formed by 1959. That's when he decided he would prefer peddling himself as a maker of golf courses rather than insurance policies.

"Pete's boss couldn't believe he could do such a thing," recalls Alice. "Nobody ever heard of a golf course architect then." In fact, when Pete first used the term, Alice's father, an attorney, told him he couldn't; he didn't have an architectural degree. (Or any other, for that matter; he left high school, college and law school shy of a sheepskin.) "But I never doubted for a moment that it wasn't gonna be OK."

At first, that's all it was -- OK. Pete didn't have a style yet, just enthusiasm and ambition. He placed small advertisements in Golf World and knocked on doors. Some jobs around town answered, and his friend Jones told the University of Michigan to hire him to stir up an 18 to complement the 18 MacKenzie had crafted years earlier. "The damned thing I did looked so much like Trent had done it," Dye chortles, "that he always told me it was one of my best."

Then came 1963 and the revelations that would change him … and golf. Pete qualified for the British Amateur at St. Andrews, and the Dyes inhaled linksland's charm. Each course they visited presented possibilities they had never imagined. "It blew my mind," he remembers. "Everything for me changed dramatically."

At Turnberry they were stunned by the dunes, the openness and sheer vastness, all so foreign to golf in the Midwest. Prestwick introduced them to railroad ties as visible obstacles and contrasting textures. Carnoustie made plain the need to control the drive and the challenge of uneven terrain. Dornoch presented the openness of the greens and the enchantment of the sea. And, at St. Andrews -- "I thought it was the worst golf course I'd ever seen the first time I played it," remembers Pete, "and then I was lucky enough to win a few matches and keep playing it enough that I came to see how this thing was set up" -- they embraced the beauty of clean playing lines and how the land's movement and features govern strategy.

Already working on Crooked Stick, "When I came back to the States, I had the idea I had to try to make it look like some of those courses over there. Now, you're in clay dirt here. You're not in sand. You're fighting city hall." He fought it anyway. "I tried to change." Did he ever.

The man who would re-route American design had crossed the threshold to his future. By going all the way back to golf's cradle, Pete Dye found his way.

"Given the railroad ties and some of the other features," says Doak, "some people think of his work as pop art. They think of it as New Age. They don't think of it as retro. But his inspiration is in the Old World."

Urbina: "He's taken the classical templates, disguised them, and made them his own. His angles are classical. His strategy is classical. His courses are classical. But you don't see it until you really see it."

You don't see it right away because what would be the fun in that? Design is mystery, and the better the player, the more intriguing the mysteries Dye presents. Like a magician, he redirects attention. How can you zero in on the flag when all you see are sandy waste areas and rows and rows of railroad ties? How can you keep your eyes on business when the sea is calling? How can you keep your mind on the green when it's surrounded on all sides by water?

"Pete used illusion and deception to a much higher level than the game had seen in years," contends Weed. "His design is probably more mentally challenging than any other architect's."

For Dye, it's simple, really. "The thing that gets to a good player is fear," he says, and his work, on the surface, instills it. "I try to make things look hard, but play easy," he says. "I think people misinterpret what I try to do. My courses aren't really that hard. They just look hard."

Consider TPC Sawgrass' Players Stadium Course.

Based largely on his admiration for Harbour Town, former PGA Tour commissioner Deane Beman sought out Dye in 1979 to find a golf course in the Ponte Vedra muck that could annually test the greatest players in the galaxy. To this day Beman maintains that the Stadium Course has never fully gotten its due. Remember the hubbub when it first opened? How the players hated it? How they thought the greens -- that Dye had already tempered twice -- belonged in a Coney Island fun house? How Ben Crenshaw -- Gentle Ben, for goodness' sake -- dubbed it "Star Wars golf created by Darth Vader"? How Jerry Pate, who won the first Players contested there, offered visual critique at the trophy presentation by tossing Dye and Beman into the pond beside the 18th hole before diving in after them?

It's all part of Sawgrass lore -- "I was glad for it," says Dye. "It put us on the map" -- but to Beman, it only clouded Dye's achievement. "This course and Pete's job here is well recognized," he emphasizes, "but underappreciated."

Unless you accepted his intent. "He wasn't trying to be popular," stresses Nicklaus. "He was trying to challenge the game of golf."

And he did. He did it by raising his own game to that higher gear Coore alludes to. Part of it comes through redefining classical lines of play and part through use of nature itself -- via the wind -- though those two strands are one in Dye's arsenal. Given the site, he had a completely blank canvas to build on; he could devise features from lakes to spectator mounds to rolling greens to fairways that wriggled this way and that, any way he saw fit. (A few years later, when Dye was about to carve PGA West out of a Palm Springs pancake, co-owner Joe Walser thought, "This is the perfect site for Pete. If there were a hill or a stream, he might have to compromise.")

Back then, players weren't used to hitting long shots into prevailing breezes and short shots with them; the idea flew in the face of design wisdom. Dye liked that. "It makes them uncomfortable," he says. It put longer clubs in their hands on second shots. It also helped make a short course play longer, as do those angles of play. With the exception of the four par 3s -- "It's the first course I ever did where they all go in different directions" -- every hole has at least one slight turn in it and usually two, forcing players to work the ball on both drive and approach, and, because of where they turn, to think hard before pulling any triggers.

"When you build a golf course and the strategy is so simple," Dye says, "sometimes what you see gets you overthinking things." Take the seemingly straightforward opener. "There's plenty of fairway, and then they have nothing but an 8-iron shot. Left-to-right off the tee. Right-to-left into the green. Why in the hell do they miss that green? I just sit there and wonder."

But he knows. They miss because he's inserted the questions that led them to weigh macros, assess micros and then take something off the drive for safety -- to avoid missing left. Which leaves a much more difficult path to the green. "This is a real second-shot golf course," explains Beman. "If you decide to take something off the tee shot to position yourself to not get into the little turns of the holes, you're confronted with a much more difficult shot than you've avoided off the tee in the first place."

Dye-think in a nutshell.

Add to that the challenges around the greens, where players face delicate chips and pitches instead of a constant hack out of bunkers or tall grass, and something else becomes manifest: The Stadium Course's panoply of decisions cumulatively grinds players down. From Beman's perspective, "It makes for what may be the ultimate strategic golf course that the tour players play."

And we haven't gotten to the final three holes yet. "The moment they book a tee time," says Dye, smiling, "they start thinking about 17," which makes it pretty much perfect.

Still, despite his tinkering through the years, he wouldn't mind another go at it. "It needs to be stronger," he says. "The greens are OK. The bunkering is good. But you've got places where you can add length. Bring some of the par 4s back to 520, but in a way" -- a little turn here, a little turn there -- "that stops a Dustin Johnson from hitting 340 without thinking about it."

Length -- and the need to expand courses to accommodate the changes in the game -- has made Dye dyspeptic for decades. "The USGA just had this big fight over the putter. The problem isn't the putter," Dye says. "The problem is when Nicklaus was in his prime, he hit the ball 265 yards. Now they hit the ball 325 yards, and their 8-irons 180. When you're building a course, you have to account for that, and still make it fit for women and old men to play. And that can keep you up at night. Not many of the young guys have been able to figure this deal out. So a lot of them build too hard. Courses like that are no fun to play."

Nor are they easy to maintain to pristine Augusta standards -- favored resort courses of Dye's such as TPC Sawgrass and Kiawah and Whistling Straits and Teeth of the Dog are not easy to maintain, either -- which raises the price tag of the game. "When I first built a course, there was no maintenance," he says. "Now everyone expects a certain amount right down the line from the TPC to the muny. Everything escalated. It hurts the game. I'm as guilty as anyone. I've done a bad job on that."

For Dye, that is less a regret than a nod to reality. He is about the present. On the verge of his 10th decade, he still carries a 2-iron, still lives and breathes the game, and still has courses to build.

He leads me from the Florida room, through the kitchen, to his world headquarters. "Everybody has a big office," he says. "A bunch of people. Shows they're important. This is mine." It's the dining room. A portrait of Alice's father looks down from the wall reminding Pete, perhaps, that he's a builder, not an architect. The table is piled with projects, like Gulf Stream, in need of completion, and -- no surprise -- there's no drawing board. He produces a topographic map of White Oak Plantation, north of Jacksonville, that he's filled with scratches and notes, and some tracing paper, with more scratches: his version of 18 stakes in the ground. "It's as far as I've gotten," he says, but he's been out to walk the land, and will eventually figure it all out. "Then I'll take this" -- his scratchings -- "and clean it up, then get a guy to make a nice drawing."

The dirt, as ever, will be his.