From The Archive

Remembering a Tragedy: Lost in The Fog

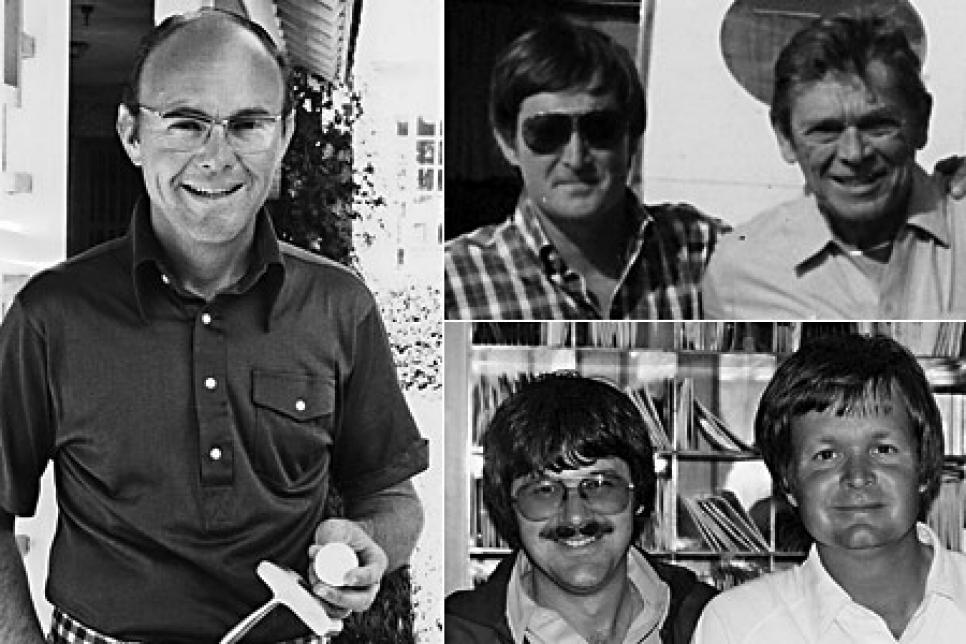

Davis Love, Jr. (far left); Pilot Chip Worthington (top left) picked up an early love of flying from his father Frank Worthington Jr.; John Popa (bottom left) and Jimmy Hodges were close friends and golf professionals at Sea Island G.C.

Dramatic, even tragic, events often are preceded by the mundane. Such was the case on Nov. 13, 1988. As four families conducted their lives in a Georgia town, there were no signs the world as they knew it -- comfortable, predictable, safe as a triple-locked door -- was about to be shattered.

It was a Sunday on St. Simons Island, Ga., where everybody knew everybody, or near about, where folks put up with sleepy because they got charm in the bargain. It wasn't where you lived, it was home. Sure, the holidays were around the corner, but this was a put-your-feet-up or catch-up-on-some-chores time. Until a few hours after sunset, things were as normal as normal gets.

After the morning fog burned off, the temperature warmed into the mid-70s. In the afternoon Davis M. Love Jr. watched some football on television, then went with Penta, his wife of 26 years, as she hit golf balls on the Sea Island GC range. Not far away, Jimmy and Susie Hodges were putting in an irrigation system on the lawn of a new home they and their three children were about to move into.

John Popa, their friend and colleague, had taken care of a household duty the day before. "I sent John to the grocery store, which he did sometimes, but not very often," remembers his wife, Cheryl. "I told him we needed a box of Kleenex, some toilet paper and a few other things. He came home from the Winn-Dixie with five or six boxes of Kleenex. I said, 'What are you buying all this Kleenex for?' "

Frank S. (Chip) Worthington III worked for a holding company in addition to flying for Glynco TAJ Aviation, an air taxi company based out of nearby Brunswick airport. "Lot of times on Sunday, we'd ride around and he'd show me the projects that the holding company was doing," says his wife, Marilyn Worthington. "They had a new subdivision. He had a flight earlier that day. We rode around, had lunch. He came back home and made sausage cheese-ball appetizers and put those in the freezer for later on. We had a very nice Sunday."

But Worthington had another task before he could enjoy his homemade snacks. He would be flying Davis Love Jr., Jimmy Hodges and John Popa from St. Simons Island to Jacksonville International Airport that evening in time for the trio to catch Piedmont Airlines flight 1535, a 9:30 p.m. departure to Tampa. The three pros were heading to Innisbrook Resort in Tarpon Springs, Fla., for an annual meeting of the Golf Digest Schools instruction staff. It was only about a 70-mile drive from St. Simons to Jacksonville International, but the short-hop flight wasn't too expensive and allowed Love and his associates more time at home before leaving on their trip.

Davis Love Jr., 53, was one of the most respected teachers in golf. He knew the swing chapter and verse -- antique Seymour Dunn was a favorite -- but was smart enough to deliver to his students only the relevant fragments that would help them. His common-sense touch, his ability to inform rather than inundate, made sense considering he had been tutored by a master of simplicity, Harvey Penick, his coach at Texas in the 1950s. Love didn't have a little red book, preferring to keep stationers in business by making copious notes on countless legal pads. He also was a player -- as the old-timers said, someone used to having a score after his name. He was good enough to have finished T-6 in the 1969 British Open alongside Jack Nicklaus, gritty enough to have qualified at Winged Foot for the 1960 U.S. Open despite six stitches in his right index finger that required him to bunt the ball around with a bag full of lofted woods and utilize his stellar short game.

Love's best-known pupil, his older son, Davis III, had notched one PGA Tour victory in 1987, his second year on tour. Only 24, the father's namesake seemed destined for greatness thanks to a precocious game marked by head-turning power. "I never saw a father-son relationship that was as good as Davis Jr. and Davis III's," says Bob Toski, a key Golf Digest Schools instructor. Mark Love, two years younger than Davis III, also was close to his dad, who was careful never to slight him as Davis III's profile increased even though others occasionally did. "Dad was pretty adamant with making sure you didn't equate your golf game with who you were," Mark says.

Mark Love caddied for his brother, Davis, for some time out on tour.

Stan Badz/Getty Images

If James Oliver Hodges V, 35, hadn't been known as plain old "Jimmy," something would have been out of whack. Hodges was a Southerner through and through, a native of Milledgeville, Ga., blessed with an easy manner and quick wit. "Jimmy was the funniest man I ever met," says Ray Cutright, an old friend, "and he didn't even have to say anything to be funny." Hodges taught with Love at Sea Island GC, and their relationship went way beyond mentor-protégé. "Jimmy even walked like Davis," recalls Jim Stahl, a frequent visitor to Sea Island. "Davis walked with splayed feet, and Jimmy was the same way. Sometimes Jimmy tied his shoes, and sometimes he didn't. He was a real guy."

Hodges, who loved to teach juniors, also was Davis III's best friend, a devoted fellow hunter and fisherman. "The minute he saw a duck fly overhead, he forgot about golf," says his wife, Susie. "Fishing. Turkeys in the spring. Hogs. All of that." But Hodges also spent plenty of time, with the blessing of Davis Jr., helping Davis III hone his swing and mediating when there was a disagreement about a lesson point between father and son. "He was going to be the next great teacher," Cutright says of Hodges.

John Popa, 37, was Sea Island's head pro, a man known for his genuine nature and organizational skills. Originally from Hubbard, Ohio, a small town in the northeast part of the state, Popa overcame tragedy when he was 10 years old and his father died from injuries sustained when a large truck hit his car. Popa had left Youngstown State and was an assistant pro in California in 1978 when he met Cheryl Wrede.

"I got there in September, but we didn't date until the following May," she recalls. "He wasn't very nice to me, and I thought he was a geek. One day we had a putting contest after work. By then I thought he was nice, and he liked me because I was a Lakers fan." Popa got a job offer to be an assistant at Sea Island, asked Cheryl to marry him and moved east. In the 1980s Sea Island was the hub for the Golf Digest Schools, and Popa frequently collaborated with the director, Andy Nusbaum. "We worked closely on developing a learning center at Sea Island," says Nusbaum, "He was just such an easygoing, good guy to work with, organized, [always] anticipating what would come next."

Worthington was 39. He was born in Charlotte but grew up in northern Virginia. He had gone by "Chip" since he was old enough to make a paper airplane. His father, Frank S. Jr., had a plane and exposed Chip and his younger brother, Ed, to flying. "I never really got the bug, but Chip did," Ed says. "He loved to fly; it was his passion. He was meticulous about it." Worthington went to Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Fla., but his hopes of working for an airline were hampered by a glut of retired military pilots entering the workforce. "With Vietnam veterans who had 5,000 hours [flying time], they weren't even going to look at someone with 1,000 hours," Marilyn says. "He chose a different path."

He was a commercial instrument-rated pilot with about 1,600 hours of flying time on Nov. 13, 1988, when he flew from Brunswick airport to St. Simons airport in a Piper Cherokee Archer PA 28-181, registration N8342L. On radio transmissions, it was "Four Two Lima." It was a four-seat, single engine model with a low-wing configuration. Love and his colleagues had expected a bigger aircraft and were disappointed that a smaller plane had been dispatched. Love had flown with Worthington, and he expressed pleasure to see the pilot on the tarmac. But there wasn't room on the Piper for the pros' golf bags.

"When Davis got into the plane, he did something odd," Penta Love remembered in Davis III's 1997 memoir Every Shot I Take. "Although he had already kissed me goodbye, he came out of the plane, walked to the car and kissed me goodbye again."

The notion of taking the short flight hadn't made sense to Popa. "John, when he left the house that night, said, 'This is the craziest thing. I don't know why we're flying to Jacksonville,' " Cheryl says. "He was always kind of a nervous flier, when we'd go visit his mother in Ohio or go somewhere else. It's kind of creepy to look back now, but he was fearful of dying in a plane crash. When they left here, though, it was crystal-clear on St. Simons. I had friends who flew with [Worthington], and they said they would fly anywhere with him because he was such a careful guy, a careful pilot."

Worthington checked the weather before taking off in Brunswick; depending on exactly when he called flight service, he could have heard that Jacksonville weather was either five miles with haze or occasional visibility two miles with fog. He filed a VFR (visual flight rules) plan, and it was 8:23 p.m. when he left St. Simons Airport with Hodges in the seat next to him; Love and Popa were seated behind them. At 8:31:13, Worthington contacted JAX approach. At 8:31:48, controller Ronald Singletary responded, "We're landing on runway seven, the weather is sky partially obscured, visibility one mile, fog, wind calm, altimeter is three zero one eight."

Almost six minutes later, at 8:37:34, Singletary updated the weather with a broadcast to all aircraft: "Attention all aircraft; tower visibility one half mile."

Between 8:37:44 and 8:37:55 Singletary separately told three different aircraft visibility was one-quarter mile but did not provide this information to Four Two Lima. Less than a minute later, Worthington asked the controller, " … uh can we get an IFR in there sir?" At 8:39:13, local controller Steven Stump told approach controller Singletary: "Yeah, I just want you to know, be ready for the missed approaches, it's getting real bad."

Singletary advised Worthington at 8:39:20, to "continue your present heading, you're cleared to JAX International via radar vectors, maintain two thousand, expect ILS [instrument landing system] approach [for runway] seven." At 8:48:24 Four Two Lima was cleared for the ILS approach to runway seven.

A special weather observation noting the existence of a measured broken ceiling at 100 feet with a visibility limited to 1/16th of a mile by fog was received in the tower over the JAX National Weather Service electrowriter at 8:51:00. The information was not given to the controllers.

At 8:51:56, Stump broadcast to Worthington: "Cherokee eight three four two lima, roger runway seven cleared to land, the uh visib-- … er uh stand by, the RVR [runway visual range] is in update, however, it's been down around two thousand feet or so."

Stump informed Worthington at 8:52:08: "A couple of them have missed the approach and Ameri -- an er American jet landed, advised he broke out just about right at minimums." Worthington acknowledged the transmission when his plane was 1½ miles out at an altitude of about 800 feet. "OK four two lima, thank ya," Worthington said. Those were the last words heard from Four Two Lima.

"I expected Chip back around nine," says Marilyn Worthington. "He wasn't back, so I called his car phone. He didn't answer, but it didn't alarm me, because I know how he likes to talk after a flight in the airport. I didn't think anything about it. I went to bed."

About 10 p.m. EST, Davis III, who had just arrived with his wife, Robin, in Maui, Hawaii for the Kapalua International tournament, called home. The young parents of six-month-old Lexie had left their daughter with Penta in Georgia, eager to enjoy a getaway in paradise. From the minute his mother answered, Love detected alarm. She told him the plane "had fallen off the radar." Loaded with dread but praying for a miracle, the couple caught a six-hour flight to San Francisco.

"I was still up, watching the news or doing some knitting. It was close to 11 o'clock," says Cheryl. "Tommy Kukoly, who was the director of golf, came to the door. I wondered what he was doing there so late at night. He said they couldn't find the plane."

By 3 a.m. Monday, Marilyn Worthington knew authorities were detecting a signal from Four Two Lima's emergency transponder, which was a harbinger of the worst. About 7:30 a.m., the dense fog had thinned enough so that the wreckage could be spotted. Debris was scattered, with most of the crumpled plane in three places among the trees approximately 1,400 feet left of runway seven and about 500 feet past the runway's threshold (start point). The aircraft, an investigation revealed, had been traveling in a northerly direction with its flaps fully retracted and throttle fully open when it struck trees 40 feet above the ground at 8:53:27 p.m.

Davis III and Robin landed in San Francisco and found a pay phone, the disaster confirmed in a conversation with Mark. A priest arrived at the Popa house minutes after Cheryl had heard on a Jacksonville TV station that no one survived the crash.

Nusbaum got grim confirmation after a sleepless night at Innisbrook. Along with others from Golf Digest, he headed straight for Sea Island, guilt riding shotgun with grief. "It was hard on everybody because they were coming to a meeting that we were all there for," Nusbaum says. "I remember for a while feeling, 'Gee, this was a meeting I called. I had been talking to Davis a lot on the phone making sure he was coming. You think, 'My god, did we need to do this?' "

The news overwhelmed the victims' hometown, where sadness draped the community like Spanish moss. "It was the saddest," says Bob Carney, a Golf Digest editor who collaborated with Love and Toski on their 1988 book How To Feel A Real Golf Swing. "There was a lot of goodness on that little plane."

Services on Wednesday were staggered to allow mourners the chance to attend all four. Popa's was at 10:30, followed by the rites for Hodges, Worthington and Love Jr. "That was one of, if not the hardest day of my life," says Nusbaum, a pallbearer at Love's funeral. The tiny church holding Hodges' service couldn't accommodate the crowd, which spilled outside. The scene was a metaphor for the town's outpouring of support, which far exceeded the customary casseroles and cards in the tragedy's immediate wake. "I don't think I ate a meal at home for the first year," says Marilyn Worthington, whose sons Matthew and Frank IV were 6 and 10, among seven children left without a father. "I was taken out to breakfast, to lunch, to dinner. We were able to grieve and not be isolated." Local attorney Randy Jordan, a close friend of the pros, along with Sea Island executive Bill Jones III, helped spearhead a drive to provide college educations for the victims' children.

One of Davis Jr.'s favorite lines of golf wisdom had been from Dunn, who said perseverance was about continuing in a state of grace until it is succeeded by a state of glory. The surviving Loves were a model of grace after the crash, among those paying their respects at the Worthington house. "I remember that vividly," says Ed Worthington.

"[They] never held Chip responsible for the crash. They went out of their way to be kind to Chip's wife and my family, and we appreciated that very much."

"The details or the blame -- to me -- really didn't matter," Davis III says now. "I've always moved forward, to keep me focused and sane and help everybody else get over it." Love was dealt another blow in 2003, when his brother-in-law, Jeffrey Knight, committed suicide after confessing that he had stolen almost $1 million from him. "We've kind of been through it twice, strange tragedies, and if I had sat back and [worried about] what could we have done differently and who am I mad at, I couldn't function."

On Nov. 27, 1989, the National Transportation Safety Board determined the probable causes of the accident as improper IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) procedure; improper use of decision height (the altitude at which a pilot must have the runway or its approach lights in sight to continue the approach); and a missed approach ("go-around" or aborted landing) that was not obtained. Contributing factors included fog and obscured visibility. Love III wrote in his memoir: "The details as to why the crash occurred were never fully resolved. The visibility that night was extremely poor … I feel that Dad's plane should have been warned away from even attempting to land."

Penta Love, Susie Hodges, Cheryl Popa and Marilyn Worthington filed wrongful death civil lawsuits against the United States of America for alleged negligence by two air-traffic controllers the night of the crash. The widows of the golf pros asked for $5.5 million each in damages; in a separate suit Worthington asked for $4.6 million. The plaintiffs in both cases contended that controllers failed to provide timely weather information to the pilot and improperly directed him on final approach, increasing his workload and causing him to lose control of the aircraft.

Plaintiffs and the government agreed during the trials that Worthington suffered spatial disorientation -- a loss of sense of relationship to the horizon -- as he had to decide whether or not to continue with his approach but disagreed as to its cause. Lawyers for Love, Hodges and Popa reached an out-of-court settlement. U. S. District judge John Nangle ruled against Worthington in her suit, writing in his decision that "the proximate cause of the crash … was Worthington's failure to operate his plane with the appropriate degree of care at the most critical point in its flight."

Worthington appealed the decision to the 11th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, which disagreed with Nangle's ruling, concluding that the pilot's disorientation that preceded the crash "was proximately caused by the air traffic controllers' negligence." The court wrote: "Spatial disorientation and the failure to successfully execute a missed approach are precisely the harm that this defendant should have expected after depriving Mr. Worthington of accurate and timely information about weather conditions when he approached a landing strip shrouded in fog." After the appeal, Worthington also reached an out-of-court settlement.

The lawsuits over, life went on as well as it could. "You're numb. I was numb for a long time," says Susie Hodges, who left the island for a while but returned so her sons could attend Glynn Academy in Brunswick. Cheryl Popa never left St. Simons and in 1998 married manufacturing executive Tucker Grigg, who had lost his wife to cancer. Marilyn Worthington eventually left Georgia and is a realtor in her native North Carolina. "There was always somebody there to make sure we were OK," she says of St. Simons, "but moving away kind of clears your head a little bit."

Penta Love, now 81, sought refuge in her grandchildren, at Sea Island social functions and particularly on the golf course, where she remains a 10-handicap still capable of bettering her age. "Being able to shoot your age is amazing for a man, but it happens. You don't hear ladies doing it that much," says Davis III. Adds Mark, "If there is a record, she's probably got it. She's been shooting in the mid-to-high 70s for a long time." Those kind of scores also aren't unfamiliar to the grandson Davis Jr. never got to meet, Davis M. (Dru) Love IV, a ninth-grader who is as passionate about golf as his 20-year-old sister is about Paso Fino horses.

Staying extremely busy (these days he'll watch TV while surfing the Internet and reading a magazine) helped Davis III function after the crash, but he can't count the nightmares that climaxed with tears or screams when the sorrow didn't want to stay in storage. He never stopped getting on airplanes, but he is judicious, often turning down offers to fly in private aircraft he is unfamiliar with. "I think that's what happened to Payne [Stewart, killed in a 1999 air disaster]," Love says. "He just hopped in a plane and got a really, really bad break. All the stars aligned for everything to happen wrong. I try to minimize risk and then enjoy life."

At the offices of Love Golf Design on St. Simons, a first-time visitor can be startled when planes roar closely overhead on approach to the airport, for a moment drowning out conversations and, if the sun is just right, throwing a shadow on the building. On one wall hangs a framed summary on onion-skin paper of a rudimentary nine-hole military-base course Pfc. Davis M. Love Jr. devised when he was stationed in Korea. "The first Love design," says Mark. In one of Davis III's Ryder Cup bags in a hallway sits two of their father's clubs. "This is Dad's from way back," Mark says, waggling a black-headed Royal driver. "And this, he was magic with this," he continues, picking up a Top-Flite sand wedge, its sole worn smooth by thousands of sand shots. In Mark's office is his copy of How To Feel A Real Golf Swing inscribed by his father. For Mark, Your goals will lead to your dreams -- Dad

"Once you get over the tragedy, it's the memories and the stories that you have," Davis III says. "That's how you get over it. That's how you carry on, by reminding yourself of the good things. I was lucky, I had him not just at dinner or after work or on family vacations, I would have him all day, all summer."

Many of those hot summer days were spent on the Sea Island practice turf, working on Davis III's swing, sometimes inside a makeshift perimeter of lighted cheap cigars to keep the bugs away. Love Jr., Hodges and Popa envisioned the Golf Learning Center that exists there today. The facility opened in 1991, dedicated to the three professionals who are remembered with a plaque by the front door.

Gale Peterson grew up at Sea Island and has given lessons there her whole career. In the 1980s, as a young teacher, she took note of everything Davis Jr., the balding man in the ever-present bucket hat, had to say about the craft. "I learned a lot from him," she says, smiling as she notices a white smear on her left shoe. Davis Jr. always had a can of white spray paint to indicate the arc and target line for his students.

"Davis used to ask me every day: 'What did you learn from your teaching?'" Peterson says. For too many years, she has had to pose the question to herself while pausing at the bronze likenesses of absent friends.

(This article was originally published in Golf World in 2008.)