News

One Man's Mission

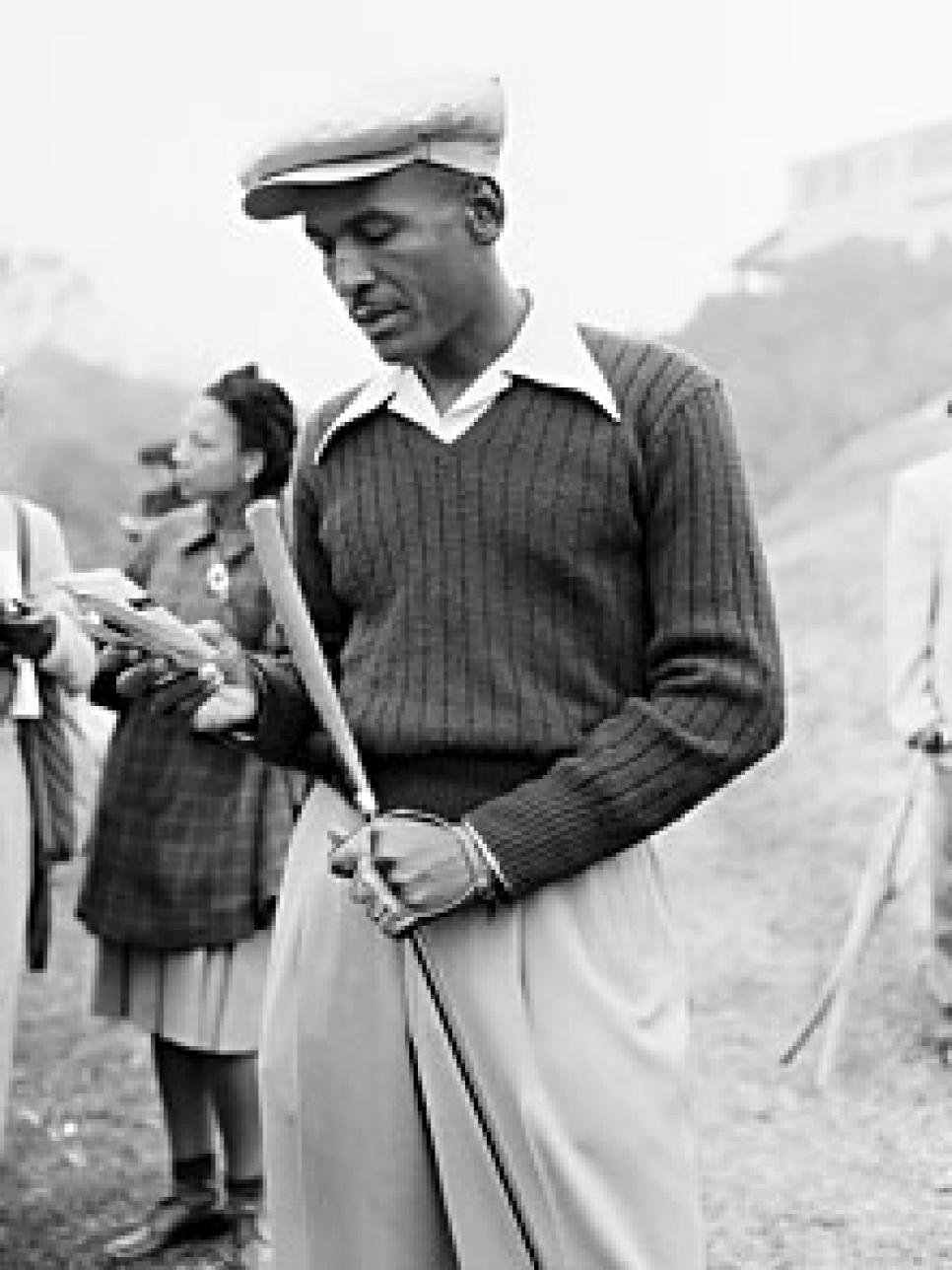

Spiller observes the putting of Louis, his frequent companion

At a glance, Richmond CC, just north of Oakland and directly across the bay from San Francisco, appears no different than most other private clubs in the United States. There is a sturdily built stucco-and-brick two-story clubhouse in the Tudor style; rich green, kempt grounds; a quiet, unhurried air. In the men's locker room, however, there are photographs on the walls indicating that in this place a bit of golf history was made. They are pictures of Sam Snead, Toney Penna, George Schoux and E.J. (Dutch) Harrison when they won the Richmond Open, a tournament played from 1945 through 1948 as part of the pro tour's winter West Coast swing. Then again, if a picture that was never taken also dressed the wall, it would peg the club as the site where a considerably more significant historical event took place than the likes of a Sam Snead winning a golf tournament. It would show two black pros who were denied the chance to compete in the 1948 Richmond Open because of the color of their skin. And as a result, it was there where one of those two men, Bill Spiller, opened the struggle to change that order of things.

Among those in the U.S. black community, Spiller was particularly unwilling to go slow in the struggle for equal opportunity. He wanted what should have been his, now. He wanted to play on the pro tour, the real pro tour, the one the white guys played. He finally did, but by the time his singular effort took root to end black discrimination in American golf, and in particular on the U.S. pro tour, he was well beyond his playing prime. It was a personal loss he felt more and more heavily, even tragically, as he ended his days. What is more, although every African-American who has played the PGA Tour since 1948 owes Spiller a great debt, he has yet to get the large portion of recognition he earned. Spiller embodied the theory that one individual's action can alter the course of history. But there are times, it seems, when that catalyst for change gets lost between the pages.

Sixty years ago, in January 1948, Bill Spiller and Ted Rhodes traveled to Richmond, Calif., to play in the Richmond Open. They had finished in the top 60 in the Los Angeles Open two weeks earlier and, according to tour regulations, were automatically qualified into the field at Richmond. The tour was then under the jurisdiction of the PGA of America (not today's PGA Tour, an entity that did not exist at the time), whose main reason for being was (and is) to train and certify club professionals. It began overseeing the pro tour in the mid-1930s because the growing circuit needed an organizing arm. After finishing a Tuesday practice round at Richmond CC, Spiller, Rhodes and local black amateur Madison Gunter were told by George Schneiter, the PGA's on-site tournament representative (and himself a competitor), that they would not be allowed to play in the tournament. The reason? They were not members of the PGA of America, a requirement for competing in tournaments it co-sponsored. Catch-22! Spiller and Rhodes could not join the association, because a clause in its constitution allowed membership only to Caucasians. Spiller had heard through the rumor mill of this blatantly racist restriction but had never seen it in writing or in any other official form. He went to Richmond to find out if it was indeed the case. By virtue of his resolute curiosity, this well-kept secret was made public for the first time.

Upon the rejection of the trio's entries, Rhodes, a quiet, non-combative man, was prepared simply to pack his bags and head home without comment. Spiller was not so disposed. He located Jonathan Rowell, a progressive, white Bay Area attorney who had represented the NAACP on some discrimination issues. Spiller asked about suing the PGA of America. On an expenses-only basis, Rowell took the case and filed a $315,000 suit: $5,000 per man against Richmond CC for prize money and humiliation; $100,000 each against the PGA of America, which was Spiller's main target. Pat Markovich, pro/manager of the Richmond club and tournament director, had no problem with black players competing, but his hands were tied by a standard contract sponsors signed with the PGA that gave the association an absolute mandate on the makeup of the competitive field. It was a contract George S. May, who staged the Tam O'Shanter All-American and World tournaments in Chicago, did not sign, and in 1942 he became the first U.S. sponsor to integrate a tournament field. The Los Angeles Open sponsors followed suit as did those of the St. Paul (Minn.) Open. Those three events were the only ones on the pro tour in the U.S. in which black pros were given a chance to compete against their white contemporaries. The U.S. Open was not segregated, but black participation was not encouraged (another story, altogether).

The suit Rowell brought claimed that Spiller and Rhodes were being denied their right to earn a living as professional golfers and was based on the PGA being a closed shop, which under the Taft-Hartley Act was against the law. A court hearing was scheduled for the following September, and Spiller and Rhodes did not play at Richmond. However, a few days before the court date, Rowell met with the PGA's attorney, who said if the suit was dropped the association would no longer discriminate against blacks. Rowell took that word in good faith, which was not returned in kind. The suit was dropped, but the plaintiffs were snookered. The PGA suggested the sponsors begin calling their tournaments "Open Invitationals," invitational being the operative word. The deceit had virtually total participation. No blacks got invitations.

It was not the end of the story, of course, although the golf establishment and the press effectively buried it for four years. In that time Spiller could not pursue the issue if only because he didn't have the means. He lived in Los Angeles while Rowell, who lived in the Bay Area and had gotten into elective politics, was no longer able to pursue the matter. Furthermore, Spiller and his wife, Goldie, began raising a family that eventually numbered three children. Except for Maggie Hathaway, an energetic black activist in Los Angeles with a newspaper column through which she spoke out, no other blacks appeared inclined to attack segregation in mainstream American professional golf. Spiller once stood a lone picket at a local tournament in Long Beach, Calif., that denied black entries, but the protest gained little notice.

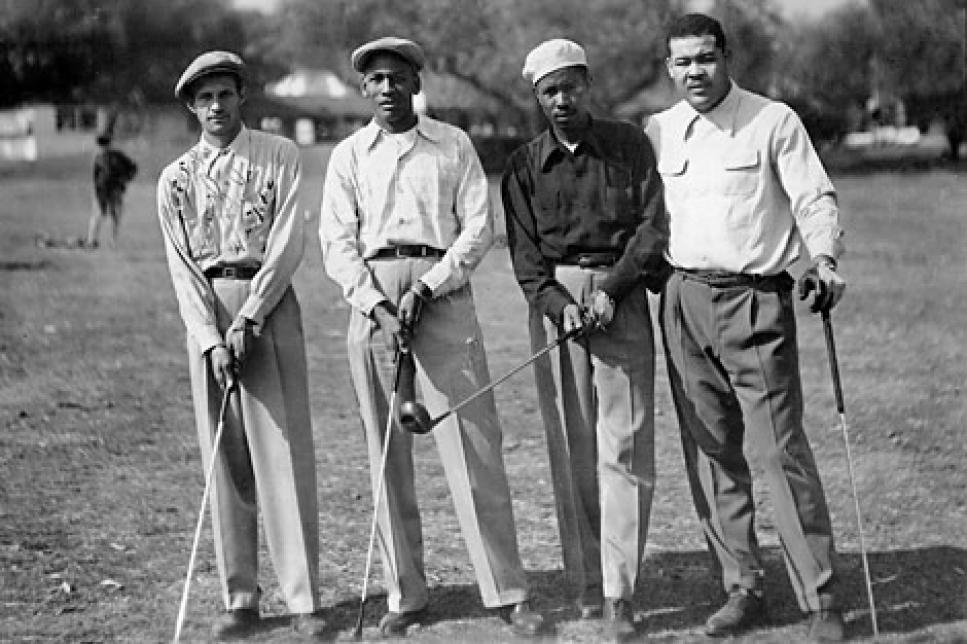

Then, in 1952, another real opportunity arose. This time Spiller had a celebrated ally who brought to it maximum public awareness. The sponsors of the San Diego Open, looking to get attention for their inaugural tournament, and perhaps unaware of the Caucasians-only clause, invited former heavyweight champion Joe Louis to play in the event. They were following George S. May's lead. May gave Louis a sponsor's exemption as far back as 1945, not only because he was black but was a draw at the gate. Louis was a zealous amateur golfer with a high single-digit handicap. Rhodes, one of the best black golfers in the game's history, was Louis' personal pro, and Spiller played a lot of golf with Louis. The San Diego people also invited Spiller and Eural Clark, a talented southern California black amateur, to try to qualify. Louis accepted the invitation, as did Spiller and Clark. Spiller qualified, Clark did not. Then, the Richmond scenario was replayed, with a twist. Not only was Spiller barred, but so was Louis. No reason was given publicly, but everyone knew it was because he was black.

Spiller had apprised Louis that this might be coming and advised him to accept the invitation, because he was certain that when one of the most famous athletes in the world was prohibited from playing, the discrimination issue would be revived and receive significant publicity. It did just that. As the first black heavyweight champion since the flamboyant Jack Johnson, Louis had been trained to be quiet, unassuming and to not react to racist taunts. But having recently had his last fight -- taking a severe beating from Rocky Marciano -- he no longer felt bound by that propriety.

When told he was barred, Louis said of Horton Smith, president of the PGA and the man who informed him of his exclusion, "We've got another Hitler to get by … Horton Smith believes in the white race [the way] Hitler believed in the super race." Louis also took it upon himself to phone Walter Winchell, a popular nationally syndicated newspaper columnist who also had a weekly radio program with a large audience, to tell him what was going on in San Diego. Winchell aired the story on the radio, commenting that if Louis could serve his country in the U.S. Army, he could surely carry a golf club in San Diego. Or words to that effect. A substantial clamor arose, with newspapers around the country reporting on it. To tamp it, Smith called a meeting with Louis; his secretary, Leonard Reed; Eural Clark; tour pros Leland Gibson and Jack Burke Jr.; and San Diego Open officials. Spiller was not invited to attend, surely to avoid his tongue, and was unaware it was going on until Jimmy Demaret spotted him on the grounds and said he should be in the room. According to Spiller's account in the book Gettin' to the Dance Floor, an Oral History of American Golf, when he entered the room, Smith acknowledged him and said, "You're Bill Spiller aren't you? Is there something you want to say?" It was like un-tapping a dam. "I know and you know that we're going to play in the tournaments," said Spiller. "We all know it's coming. So if you like golf the way you say you do, and I do, I think we should make an agreement so we can play without all this adverse publicity. And take that Caucasians-only clause out of your constitution so we can have opportunities to get jobs as pros at clubs."

To the latter request, Smith said golf was a social game and, "We have to be careful who we put on a [club] job." A fuming Spiller replied, "Mr. Smith, I heard a rumor that you said if you were as big as Joe Louis, you would knock me down. Well, if I hated someone that much, I wouldn't let size bother me." The emotional temperature in the room shot through the ceiling. When Spiller asked Smith why he wasn't listed in the pairings for the first round, being that he qualified, he got the answer he knew was coming and responded, "That's not good enough for me. I'll see you in court." As he made his way out of the room, Gibson and Burke stopped Spiller and asked him to give them a chance to work it out. "Sure," said Spiller, "but you ran over me the last time and aren't going to this time." He promised not to bring the suit right away, and he never did, because things did get worked out, more or less.

As a symbolic gesture, and to gain some public relations points, Louis was allowed to play in San Diego because he was an amateur. Spiller was not and was upset that Louis did play after saying he wouldn't if Spiller was not allowed. To show his disgust with the entire situation, Spiller stood in the middle of the first tee the morning of the opening round to protest. Only after Louis talked him into moving did the tournament begin. That same week the PGA announced that black golfers could play as "Approved Entries" wherever they were invited. This time some tournament sponsors did offer invitations. The week after the San Diego showdown, Spiller, Rhodes, Louis and a young Charlie Sifford, plus two other black amateurs, were invited to qualify for the Phoenix Open.

At that, it wasn't the most salubrious welcome. All the black golfers were paired together, if only because most white pros refused to play with a black. (Johnny Bulla and Leonard Dodson didn't mind, and for his trouble Dodson was dubbed by his white cohorts as Booker T. Dodson, after the famed black educator; go figure, Booker T. Washington's father was white, and he thought black agitation for social equality was foolish.) All the blacks were sent off first at Phoenix for round one, and after holing out on the first green, Sifford found his ball atop a small mound of human feces that had been deposited in the cup. Furthermore, the blacks were told not to use the clubhouse facilities. Spiller challenged that and went in to take a shower. When someone warned Louis that his friend could be in real, physical danger, he talked Spiller into clearing out.

Still, it was a start. Rhodes and Sifford played in Tucson the week after Phoenix. Spiller failed to qualify, but over the entire year played five tour events in the West and five in the East. They were strongly advised to not try playing in the Deep South, and even Spiller understood that was a wise move. However, the Caucasians-only clause stayed on the books and access to the tour was still limited until 1961, when Spiller again got active.

As a college graduate, Bill Spiller was a rare bird in the black world of his time, especially among athletes. This background was in good part what made him an articulate challenger of the system. He earned a degree in education from Wiley College, a traditional black school in Texas (currently featured in the film "The Great Debaters"). He was going to be a teacher, but the best offer was a $60-a-month position at a black high school. It was not enough. "I can make more money shooting pool," he once told this writer. He moved to Los Angeles and took a job as a redcap at Union Station. An excellent athlete who ran track and played basketball at Wiley, Spiller took up the challenge of a fellow redcap in Los Angeles to try golf. At 29 it was a late start, but within three years he was a factor in events on the black tour, an erratic circuit with small purses (and on which whites were not barred). Spiller's most shining moment as a player was in 1948, in the first round of the Los Angeles Open. He had worked the night shift at Union Station, and the next morning took a bus to the storied Riviera CC and shot a 68 to tie for second with Ben Hogan. A Cinderella story, at least for a day. He didn't fare nearly as well the rest of the way and finished T-29 (Rhodes was T-22), but it did (or was supposed to) get him in the field at Richmond.

Spiller was motivated in his struggle by the 68 at Riviera, his successes on the black tour and by Jackie Robinson's entry into major league baseball in 1947. But his impulse had a longer and deeper history. As a boy living in Tulsa, a white storekeeper slapped him for not accepting his refusal to take back some damaged merchandise. Spiller vowed that would never happen again, and should it the perpetrator would get more back than a slap upside the head. Although there is no record of his striking anyone in anger, Spiller did not embrace Ghandian non-violent protest. He often carried a gun, and according to his son, Bill Jr., a lawyer in Los Angeles, he "pulled it a time or two."

Spiller's wife would be the family's steady breadwinner, working for the Los Angeles Water and Power Department. For a few years Spiller operated a doughnut shop he was put into by a man named Chapman, for whom he caddied at the Hillcrest CC. Chapman owned a chain of "Mrs. Chapman's Doughnut Shops." Bill called his "Mrs. Spiller's." After one too many robberies, he gave it up. He went back to caddieing at Hillcrest, but $5 a bag was hardly enough. He gave lessons on the course to Hillcrest members whose bags he toted and was so successful they petitioned for him to be hired as an assistant pro. The head pro said if that happened he would quit. The pro won the day. Over a period of years, Kenneth Hahn, a member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors for 40 years and a white conspicuously supportive of civil rights, tried often to get Spiller a job as a professional at one of the five municipal courses. But he could never get enough votes from the rest of the board to make it happen. The resistance was in large part because of Spiller's reputation as a trouble-maker.

Spiller continued to sneak lessons at Hillcrest, taught for four years at a driving range and played golf for money, sometimes for more than he had in pocket. He once clipped Joe Louis for $7,000 (Bill Spiller Jr. says it was $20,000), with which he bought the house the Spiller family came up in. (Louis liked to play for big stakes and was a well-known sure-thing "pigeon," but he may have tanked a little in this case; Louis was a generous supporter of black golfers and the black tour.) Frank Snow, a disciple of Spiller, assessed Spiller's game as having moderate length off the tee, very accurate through the bag, a steady, conservative golfer with an excellent touch around the greens. And, of course, he was also inspired to pursue his dream of making it as a big-league golfer by the L.A. Open and Tam O'Shanter tournaments, where he had opportunities to mingle in a major-league arena. Dorothy May Campbell, George May's daughter, remembered having lunch with Spiller in the Tam O'Shanter clubhouse one afternoon and Spiller being taken by surprise when asked for his autograph by some young fans.

(It is interesting to note that in 1942, when May invited nine black pros and five amateurs to qualify for his event, seven qualified and three of the pros made the cut. That was quite a good showing given that most public courses in the country, North and South, did not allow any or at best limited access to blacks. Given that result, it is probably less than coincidental that the following year was when the PGA of America inserted the Caucasians-only clause into its constitution.) Then, something very important happened. In 1960 Spiller was caddieing at Hillcrest CC for an old friend, Harry Braverman, who asked why Spiller was not teaching or playing the tournament circuit. Spiller explained the tour's limited access to blacks. Braverman recommended Spiller tell it to California attorney general Stanley Mosk, who he thought would lend a supportive ear. He did. Mosk, who would eventually sit on the California Supreme Court, told the PGA of America that if it did not amend its Caucasians-only clause it could not stage tournaments on California's public courses. At that time there were some nine events held yearly in California, including tour events and association sectional tournaments -- almost all on public courses. The PGA's initial response was that it would then play on private courses. Mosk said he would put a stop to that, as well, including the 1962 PGA Championship, which was scheduled for Hillcrest CC. What's more, Mosk contacted state attorneys general around the country, telling them of the situation, and got positive responses in almost every instance. As a result, in November 1961, the PGA of America quietly expunged the Caucasians-only clause. The action got a brief mention far back in the organization's annual report. The way was now clear to get out there, but for Spiller (and Rhodes, Howard Wheeler, Zeke Hartsfeld and other blacks who once had the potential to make it) it was too late. Now 48, Spiller simply couldn't keep up. His best finish ever was a 14th in the Labatt Open, in Canada, for which he earned a small check. "I was four under par at Fort Wayne," Spiller recalled years later, "but finished four strokes out of the money. You just can't go out and play against the best in the world with so little experience."

The only black player to take advantage of Spiller's efforts in the earliest years of the "liberation" was Charlie Sifford, who had little to do with generating the release from bondage but did suffer the indignities of racial epithets and threats to his health when he bravely played through the South in the 1960s. He was followed by Pete Brown, the first black to win a PGA-sanctioned tournament -- the 1964 Waco Turner Open -- Rafe Botts, Charlie Owens, Lee Elder, Calvin Peete and, eventually, Tiger Woods.

The last 20-odd years of Spiller's life were not nearly as adventurous, and certainly not satisfying. He was never able to fulfill the five-year apprenticeship requirement needed to become a member of the PGA of America, because no one would give him the necessary assistant professional's job. Too old to schlep golf bags as a caddie, he made a few bucks here and there giving lessons, but mainly lived off the income of his wife. It was a demeaning existence for a man of his time, no matter the color of his skin.

In the early 1980s Spiller evinced signs of dementia and delusion. He would rise from bed in the middle of the night and rant about those who had denied him his chance to be what he wanted to be, sometimes waving his gun at those ghosts. After he suffered a stroke and was operated on for an aneurysm that left a scar across the top of his scalp, he began a steep and rapid decline. When he fell getting out of the bathtub and couldn't get himself up, his wife, by then herself aging, had no choice but to have him committed to a 24-hour board-and-care facility. He died there a year later, in 1988, at 75. His body was cremated.

Spiller was a serious pusher of the envelope. But aside from his challenge to the status quo in professional tournament golf, there is another indicator of just how forward-thinking he was. At the California African-American Museum, near the campus of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, there is a small exhibit honoring Spiller. It includes some of his golf artifacts, a large picture of him in a follow-through and a blowup of an article he wrote in 1948 after the debacle at Richmond CC. The article appeared in the Los Angeles Sentinel, a newspaper with a black readership. It reads as follows: Golf is new to Negroes and colored professional golfers are finding it difficult to make a living. As a Negro professional golfer I say that I would rather see my little boy on a golf course caddieing and trying to make a golfer of himself than any other place.

Golf is an individual game -- it develops the individual. Brute strength is not the most important thing. It develops concentration and teaches courtesy and good sportsmanship (in spite of the PGA).

In our fight to curb juvenile delinquency we should investigate golf a little more and use it as one of the ways to develop good citizenship among the young. We hope that citizens of the country -- not just this community -- will get behind us in this fight to remove the "lily-white" tag that the PGA has put on golf.

Those words are, practically speaking, the creed for today's First Tee program, which, in a nice touch of irony, is directed by Joe Louis' son, Joe Louis Barrow Jr. As Spiller often said to those who thought otherwise, he wasn't only looking out for himself. He had a larger vision and had it more than a half century ahead of the crowd.