News

Centers Of Attention

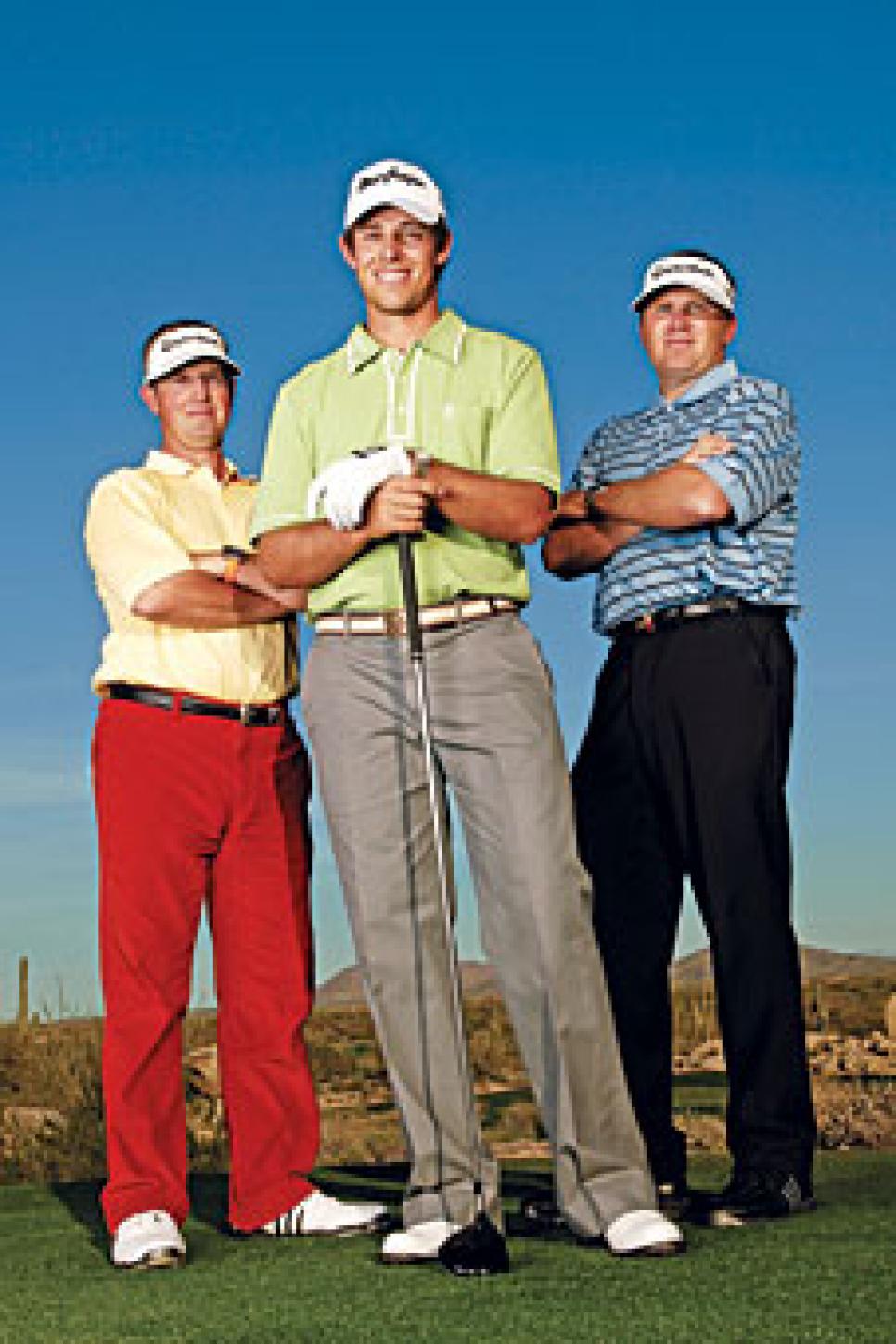

Baddeley has won twice since he started working with Bennett (left) and Plummer.

Swing coaches Andy Plummer and Mike Bennett are known on the PGA Tour as "the scientists" and "the whisperers" for the quiet way they go about their business. Their database includes more than a million—yes, a million—photographs of golfers at various stages of their swings. The centerpiece of their approach is that the most efficient swing is one in which the golfer stays centered over the ball during the backswing, while keeping his weight on the front foot. There is no effort to transfer weight. They have drawn this conclusion from their studies, and it's nearly revolutionary. Most instruction maintains that a golfer must load into the back foot to create torque and power.

Aaron Baddeley has won twice since he began working with Plummer and Bennett in fall 2005. Dean Wilson, Will MacKenzie and Eric Axley each won his first PGA Tour event last year; Plummer and Bennett have worked with more first-time winners in the last eight months than anybody. Mike Weir, the 2003 Masters champion, has been with them since late last fall. Cameras and computers in hand, the duo intends to turn golf instruction upside down or, in their view, right side up. Their files and binders are full of lines and circles and grids, because their work relies heavily on the geometry of the swing.

"You have to look at a lot of pictures of players in the same exact spot," Plummer says. "All of them have different stances, and all of them have different postures. If that's the case, then those aren't really fundamentals." But, he and Bennett claim, staying centered over the ball is a fundamental, perhaps the fundamental.

"I started with these guys two years ago when I couldn't hit the ball," Wilson says during a practice round one afternoon at the Honda Classic in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla., as Plummer walks along. "I was working as hard as I could with a teacher, and I couldn't hit the ball anywhere where I wanted to. I felt like a hack. Luckily, I ran into these guys."

Wilson goes on: "The great classic swingers—the best players, Hogan, Snead, Nicklaus—they all look like they're on top of the ball. They don't load up on their right side or restrict their hip turn. Nicklaus says you should load up to your right side, but all his weight's here." Wilson is pointing to his left foot.

Nicklaus agrees with Wilson, and, by extension, with Plummer and Bennett. "I don't believe in a lateral shift," says Nicklaus. "Of course not. I believe in staying on the ball." Asked what he thinks about teachers who advocate a weight shift, he answers, "They don't know how to play."

As for Baddeley, he credits his recent success to his more centered swing, although the idea perplexed him at first. "I had to get around a couple of things when I started to work with Mike and Andy, like staying centered instead of getting behind the ball and having my hands and arms in on my backswing. My swing's now a little shorter, and my hands are more down. I really, really enjoy working with these guys."

Plummer and Bennett have gained credibility among their fellow teaching pros, even while their approach comes in for some criticism.

"They've obviously had some success," says David Leadbetter, who worked with Baddeley before Plummer and Bennett. "I like what they've done with Aaron, the shortness of his action. There's a look of the old reverse-C in the finish position [of their players], so you hope the guys they work with have seriously mobile backs. The interesting thing to me about them is how much time they spend looking at cameras. You just wonder if by doing that, you actually own what you're doing or are you are just borrowing it, and how long it will last and if it will stand up. It's a method, not the method."

Careers, like golf balls, have trajectories. Plummer, a Kentuckian, and Bennett, from upstate New York, each planned a path to the PGA Tour. But they struggled while playing college golf and found themselves adrift in a sea of instruction.

Plummer, 40, attended Austin Peay State in Clarksville, Tenn., for a year, and then transferred to Eastern Kentucky, where he was on the golf team while majoring in economics with a minor in statistics. But he became his team's worst ball-striker. No matter how many buckets of balls he hit, or how much he studied books and tapes, he got worse.

"I couldn't figure out what was going on," he says. "I was getting not just a little worse, I couldn't hit it at all. None of the guys on my team wanted to be my partner. I went from a guy who averaged 72 or 73 in my 20-round qualifier for the team to a guy who was shooting 90."

Bennett, 39, traversed a similar path. He played junior golf at Skaneateles CC in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York. He attended East Tennessee State for a year and, like Plummer, saw his game deteriorate despite intensive studies. "It was unbelievable," he says. "I had all this information and no idea which parts were helping and which were hurting."

Plummer's and Bennett's trajectories intersected after they had become familiar with Homer Kelley's fascinating cult book The Golfing Machine. Their games improved after intensive study of the book, based on engineering principles. They came to know Mac O'Grady, the eccentric, knowledgeable former PGA Tour winner who studied Kelley's landmark work. Players such as Grant Waite and Steve Elkington have long thought O'Grady's swing is a model of efficiency and power. O'Grady, Bennett says, "taught us how to classify [swing patterns and variations]. That was the biggest light going on. If you want to do a study, the essence of science is classification. That's page one."

O'Grady introduced Plummer and Bennett to Waite, with whom he was working, and Waite introduced them to Wilson. One player begat another, in nearly biblical fashion. Last year, in short order, Wilson won the International, MacKenzie the Reno-Tahoe Open and Axley the Valero Texas Open. Wilson introduced Weir to the coaches, and he began to work with them after 10 years with instructor Mike Wilson. He couldn't prevent what he told Bennett and Plummer was a problem of "drifting" off the ball—the weight shift.

Bennett traveled to Thailand with Weir last month for the Johnnie Walker Classic. Weir took Plummer's copy of The Golfing Machine. He shot 66-78-68-67 to finish fifth, four shots behind winner Anton Haig. Weir kept drawing the ball too much in the second round and couldn't stop although he knew what to do. But as spring wore on, Weir said he had gained a deeper understanding of Plummer's and Bennett's material and that staying centered was feeling more natural. He continues to be impressed with the diligence of his teachers.

Plummer and Bennett have started working recently with Brad Faxon, who acknowledges taking more lessons from more teachers than just about anybody during his 24 years on tour. Faxon was aware of their growing reputation when he approached them earlier this year. "You have to have a guy win to make it as a coach out here," Faxon says. "You have a guy who hits perfect shots all the time, and he finishes 50th, nobody's going to want to see him."

Faxon, according to Plummer and Bennett, is a textbook case of what to do wrong, and he agrees. "I moved my center too far off the ball, I had too flat of a shoulder turn, and my center stayed way behind on the downswing, with my spine angle way back. They changed me in minutes," Faxon says of their first meeting. Of his ball-striking during tournaments, he adds, "From where I've been, it's not easy to do, but I'm seeing results. The stuff that they're teaching, they'll be teaching … in 30 years. It won't go out of vogue."

Of course, many swing theories have come and gone over the years. The list, including some methods that remain popular, includes Jimmy Ballard's "connection" approach; Eddie Merrins' "Swing the Handle, Not the Clubhead"; Jim McLean's "X-Factor" and Leadbetter's teaching of the swing as based around big muscles and two pivot points. "There's a miracle out there every week," says McLean.

That the Plummer-Bennett way may not be for everyone is evidenced by Jason Gore's recent return to his longtime teacher, Mike Miller, after a period with the duo. "I was trying to do something that I'm not physically able to do," says Gore, a barrel-chested man with short arms. Says instructor Jim Suttie: "Certain people are not built to do that. If you have a flexibility issue, you can't do that [swing as Plummer and Bennett advocate].

Plummer and Bennett can demonstrate what they preach. Bennett plans to go to tour qualifying school in the fall, "not so much that it's my dream to play out here, but to prove that I can still hit the ball and chip and putt well enough to play at that level. It's more that quest than wanting the lifestyle of playing week in and week out." Few if any swing coaches have taken the gamble of putting their games on such public display.

Bennett and Plummer are each married, with no children. They have established a research facility near Villanova in Philadelphia, in part to house their increasingly sophisticated cameras and computers. They are also working on a relationship with a course or resort as a main location. Meanwhile, they speak in one voice. "They never contradict each other," Weir says. "They are always on the same page, which gives me confidence." Waite refers to their teaching as "an inconvenient truth. It is different, and that's what I call it, an inconvenient truth."

The pair's long-term goals are both simple and audacious. "I think we're going to force the other instructors to use a little more detail or truer measurements to explain why the ball's flying where it's flying," Bennett says. "You can't just stand there and say, 'Oh, that was a good shot, that was a bad shot.' The players are going to demand better instructions. A lot of guys have been taught right off the tour."

Says Plummer: "Our goal is to change the way people think about how to swing a golf club, change the whole paradigm. To have the credibility to do that, the guys we're working with have to play well. They have to be able to demonstrate that it works. I know it works."