News

Man About Town

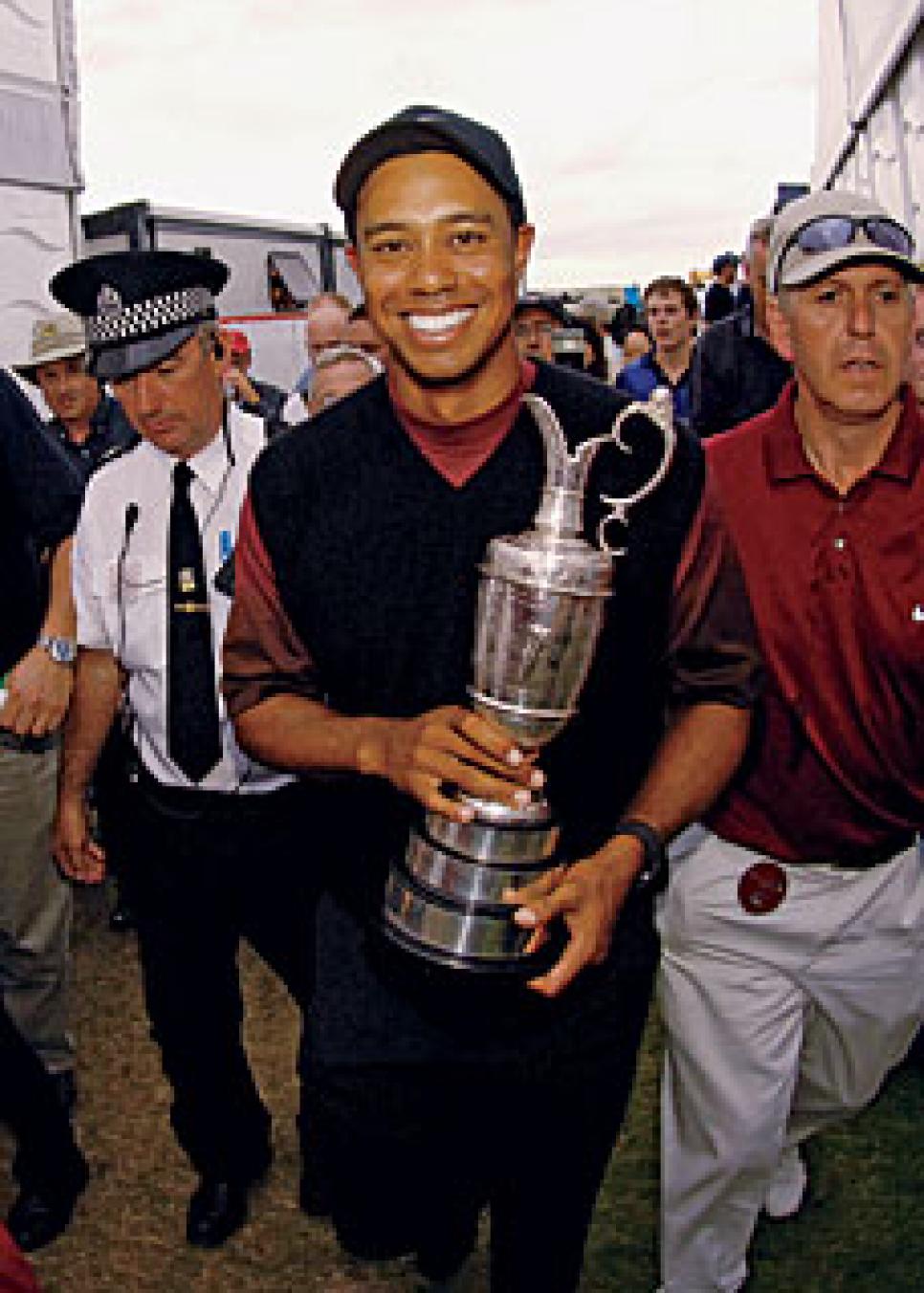

Woods' bogey at No. 6 Saturday was only a minor detour in his five-shot

By week's end, it all came down to a kid on a golf course. Just like the new television commercial, a clever transposition of time and space in which Tiger Woods wins the British Open as a 4-year-old. Owing to snippets of homemade video shot a quarter-century ago, the marvels of computer science and Woods' habit of turning a little boy's fantasy into a grown man's reality, one might humbly acknowledge the value of truth in advertising.

Just Do It? If only life were that simple. For all the moments when the burden of being the world's top golfer is greater than the result, the 134th grasping of the claret jugular reminded us that the guy who deals with the most pressure is the guy who deals with it best. Woods assumed leadership of this tournament midway through the first round and never gave it back. He spent the weekend fending off two of Europe's most decorated Ryder Cup heroes—one an owner of multiple major championships, the other a beneficiary of the heartiest home-crowd advantage you can't measure on a scorecard.

He pumped two tee shots into the gorse Saturday and missed back-to-back birdie kick-ins Sunday, yet there he was that evening, alone again. Same overcast sky, same huge lead, same timeless setting. The little boy wonder is tearing history asunder, his ability to perform on command once again equal to public demand.

And now for this public-service message: Golf's Big Five is barely alive, at least in the competitive sense. Woods' 10th professional major title (and 13th counting his three U.S. Amateurs, tying him with another guy who knew a thing or two about pressure, Bobby Jones) officially silences any lingering talk of dominance by committee, the ultra-catchy storyline that, it may turn out, was worth its weight in hype. Woods is once again supreme. "I'll tell you what—when I first started playing the tour, I honestly didn't think I'd have this many majors before the age of 30," he said, offering an updated career assessment. "There's no way."

If you're going to nail down a double career Grand Slam in 29 years, seven months and 17 days, you can do worse than to drop the hammer at St. Andrews, where Woods threatened to run and hide from the field, encountered moderate resistance in a variety of shapes and sizes, then galloped to a five-stroke triumph that was closer than the record books will indicate.

If you're going to turn 2005 into a giant I-told-you-so, you can do worse than to win the Masters, rally to finish second at the U.S. Open, then go wire-to-wire at the British Open. Asked by the BBC—then again at his post-victory news conference—for his response to those who questioned his ability to dominate as he did in 2000, Woods suggested his reply wouldn't be appropriate for any medium. "I couldn't answer that on the air," he quipped, knowing the cost of four-letter words used on television, "and I can't answer that now."

Like the ad agency that morphed the baby and bully Tigers into a snazzy marketing pitch, you'll have to use your imagination. "I think he's shown they [the critics] were incorrect in their assessment," said swing coach Hank Haney, whose 16-month working relationship with Woods is laying waste to the notion that hindsight is 20/20. "Guess I'm not so dumb after all." Every major triumph is worth savoring, even when you've reached double digits, but No. 10 may rank only behind the 1997 Masters, 2000 U.S. Open, 2000 British Open and 2001 Masters on the mega-milestone list.

Vindication?Apparently.Historic? Obviously. Ironic? What else is new? If you're going to scale the top half of Mount Nicklaus, you can do no better than to begin the climb at Jack's final major appearance, which was as emotionally powerful as a man's third or fourth retirement party could possibly be. "I should stop being a golfer more often because I birdied the last hole," the Olden Bear cracked Friday evening after rounds of 75-72 were two strokes too many from making it to the weekend. "Actually, as I was coming down the last few holes, I [was] thinking, Man, I don't want to go through this again. Maybe it's just as well I miss the cut.' These [galleries] have been wonderful. They've given of themselves, and gave me, a lot more than I deserved."

Not a chance, Jack. If you're really, really, really finished competing, then not seeing is believing. And since altered reality is a central theme here, feel free to quit six or seven more times before teeing it up in the 2006 Masters.

By 9 a.m. last Thursday, a line of hundreds had formed three blocks up the street from the Old Course, waiting outside the Royal Bank of Scotland to purchase British currency featuring Nicklaus' image on the £5 note. Only an 18-time major champion is worthy of impersonating Abraham Lincoln, although Woods ruled this old ballyard with a fist to match that of a leader more familiar to the locals, Winston Churchill. You can't do much better than to lead the field in driving distance—Woods averaged an unfathomable 341.5 yards per measured poke—and take the fewest amount of putts in the tournament (120). That's about as close as the statistics get to being unfair, especially at an event where the other two primary stats (driving accuracy and greens in regulation) are basically meaningless.

At a links casino like St. Andrews, you could tee off with a putter and putt with a driver, and nobody would look at you funny. This was as hard and bouncy as any test of premium golf in recent years, and with just enough wind throughout the week to further complicate things, the importance of ball control—especially from 50 yards and in—could not be overstated. "The greenskeeper told us the fairways are rolling just as fast as the greens," Woods said. "The only difference is the greens are softer, and not by much."

Such discriminating conditions produced a leader board with absolutely no room for a Cinderella story. Only big names factored at this British Open, bringing the Ben Curtis-Todd Hamilton underdog streak to a resounding end, and there were plenty of marquee players who nibbled at Woods throughout the week. The largest bite came from Colin Montgomerie, the robust Scot who joined Tiger in the final pairing of the third round and would finish alone in second place—by far his best performance in his national championship.

Though still majorless and graying at the temples, old Monty is actually a new Monty. He began Saturday four strokes behind but cut Woods' lead to one when he stuffed his approach at the par-4 10th. Tiger did his part by knocking his ball into unplayable lies at the sixth and ninth, but Montgomerie remained tenacious all the way to the clubhouse, holing a gnarly 15-footer for birdie at the 18th to grab a share of third with Retief Goosen, three behind Woods, one behind José Maria Olazábal.

Small victories should count for something. "I know as well as everyone else in the field that Tiger probably had his hiccup today," Monty said in an overdose of honesty. "But who knows? Who knows what can happen? There's a seven-mile walk out there tomorrow and a lot of things that can happen. If I can score a 66 out there, I'll have a chance."

Sound reasoning, except for one problem: There was no 66 out there Sunday, not on a 600-year-old venue with four drivable par 4s and a couple of very accommodating par 5s. Not from Goosen, who roared back into contention Saturday with a round of six under but pulled a quick Sunday fade similar to his demise at the U.S. Open. Not from Olazábal, the old warrior who made it into this British Open only because Seve Ballesteros, his longtime partner in crime, withdrew with an injured back and aching pride.

Like Monty, Ollie made a couple of final-round runs but was ultimately felled by his inability to drive the ball straight, a problem that has dogged him throughout his career. "I had bad swings on the sixth and 12th, and that's where my chances went," the two-time Masters champ lamented. Indeed, Olazábal's miss at the short par-4 12th proved a huge turning point. Having driven it 30 yards left of the green, Ollie found his ball behind a large ring of gorse but faced a blind pitch on an awkward angle to a front pin. His recovery effort came up short, leading to a chip that ran 10 feet past the flag.

While he was making a bogey, Woods blasted his tee shot into the light rough, then skipped a gorgeous, one-hop runner over the mound guarding the heart of the putting surface. It trickled to within six feet of the hole, resulting in a birdie that got him to14 under. Not a minute later, Montgomerie came up short on his approach at the 13th and ultimately missed a five-footer for par. Suddenly, Tiger's tenuous, two-stroke lead was up to four.

As if there was ever a doubt. While Vijay Singh and Sergio Garcia struggled all week on the greens—Garcia missed a pair of four-footers on the front nine Sunday and needed a whopping 36 putts in the final round—Woods made everything he had to make, especially in the three- to eight-foot range. While Ernie Els and Phil Mickelson were stumbling out of the gate with 74s, Woods was setting the pace with a 66, taking advantage of the early/late draw that gave him better weather than those who teed off Thursday afternoon and Friday morning.

Els seemed particularly distracted by the intangibles last week. He arrived at St. Andrews and, like Singh, noted the state of the rough, which was dry and playable in most areas but dotted with patches of thick, difficult grass. "On 17 it's the highest I've ever seen it, left and right," Els commented of the Road Hole, a brute on any day. As for Singh, he began his latest print-media embargo after stories quoted him comparing the Old Course setup to the debacle at Carnoustie in 1999. "It has become quite severe in places," noted RA chief executive Peter Dawson. "But to compare it to Carnoustie, I find astonishing."

Speaking of which, Woods' most outlandish feat at the 2000 British—he is remembered more for not playing from a single bunker than his eight-stroke victory—was not to be duplicated this time around. On his maiden voyage around the loop, he drilled a 320-yard 3-wood into fairway sand at the par-4 seventh. Oddsmakers had established his 25th hole of the week as the over/under for such an occasion, meaning they had the right hole, just the wrong day. "Probably the only place [from] where I could get it close to that front pin," Tiger handily pointed out. He spun a full wedge across the hole, darn near jarring the shot for eagle, then successfully negotiated the remaining six feet. It ignited a run of five birdies over his next six holes.

As Nicklaus was making his final, glorious exit, Woods was staking claim to the second-largest lead of his career at halftime of a major—only at the 2000 U.S. Open, where he led by six, did he take a bigger cushion into Saturday. This wouldn't turn into a rout of even comparable proportions, but it does represent a crucial point in theevolutionofthe Woods/Haneyexperiment. "It's nice to see him strike the ball the way I know he can," the swing coach said. "He hasn't shown this level to anyone else, but I've seen it [in practice sessions]. Every day, he wants to get better. That's why we get along so well."

In the Masters playoff win over Chris DiMarco, Woods played streaky golf, particularly from tee to green. Basically, he won the tournament with seven consecutive birdies in the third round—and by producing what he called his two best swings of the week in sudden death. It was almost like the guy won despite himself, which takes us to Pinehurst, where Tiger hit it wonderfully, rolled it horribly and didn't get it done. In this camp, that amounts to a positive. "If you finish 80th in the field in putting, you shouldn't be in contention to win the U.S. Open," Woods said. "I was right there with a few holes to go. That's pretty exciting to [have a chance to] win tournaments with quality ball-striking. If you putt well, you obviously win by a lot."

That's what you'd call a five-stroke victory at the 2005 British Open, Woods' most balanced display of brilliance since the miracle season of 2000. Just one player, Graeme McDowell, made fewer bogeys than Tiger's seven, and nobody made more birdies than Tiger's 21. He didn't have a 6 on his scorecard. And other than his aggressive play off the 10th tee—he went with his driver and caught the last pot bunker protecting the front-right pin—there was nothing during the final round one might even remotely classify as a mistake.

Something old is something new. In the winning camp, no one's blue. "I warmed up so well," Woods said of his final-round preparation. "One of the best warm-up sessions I've ever had in my life. I wanted to carry it to the golf course, and I did. My only bad shot was on 13, and I pulled it 10 feet. That was it. It was one of those rounds I'll be thinking about for a long time."

So might we all. At one point in the grueling post-victory process—media, more media, champagne, hysteria, media, photos—Tiger actually left behind the claret jug, the very reason he came. You might say he retrieved it in style, as if there won't be more where that came from.

.jpg)