News

Harding's Hero

Sandy Tatum and Harding Park seemed an odd couple when they became inextricably linked six years ago.

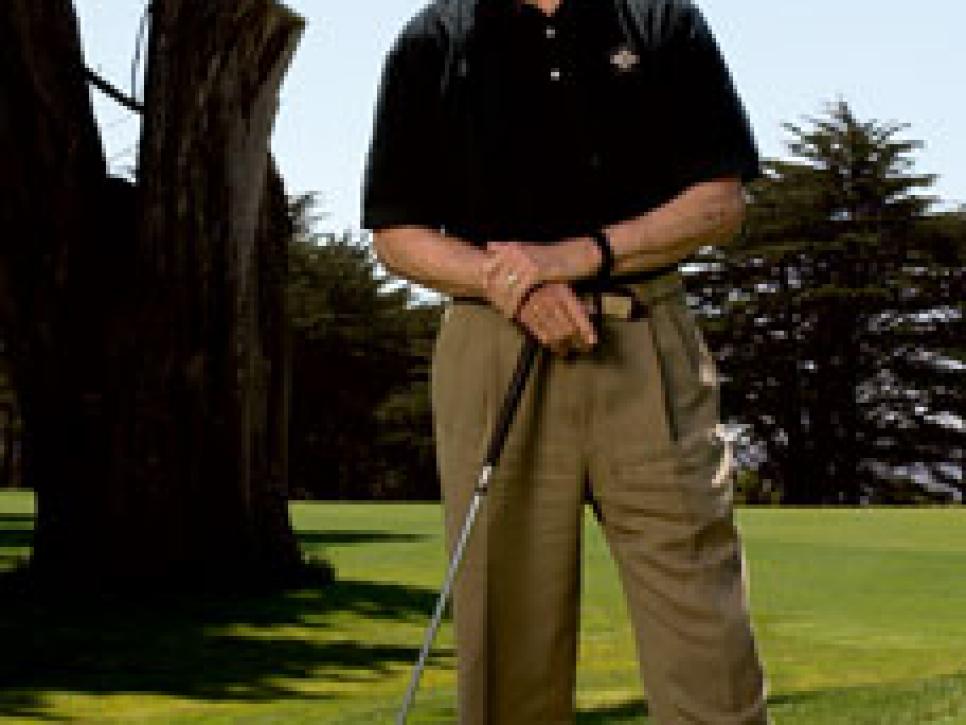

On one hand was the now 82-year-old former USGA president, a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Stanford and Rhodes scholar at Oxford, a distinguished and still-active barrister from an old-line San Francisco law firm, a member at Cypress Point and San Francisco GC, a resident of the city's exclusive Presidio Heights. With close friend Alistair Cooke he shares a gift for both gravitus and epigrammatic eloquence, as evidenced by his memorable defense of the course set-up at the 1974 U.S. Open at Winged Foot: "Our objective is not to humiliate the best players in the world. It's to identify them." To top it off, Tatum is still a trim 6-feet-2 and possesses the kind of rugged visage Harrison Ford can only hope for in 22 years.

On the other hand was the now 78-year-old golf course, the very definition of a tattered muny, its dank stucco clubhouse echoey with the clatter of pullcarts, its patchy fairways pushing up daisies, its greens rock-hard despite the ever-dampening fog, tended by too few city workers supervised by beaten-down administrators. The place may have spawned Ken Venturi, George Archer and Johnny Miller, and it may have staged the fabled 1956 San Francisco City Golf Championship final between Venturi and Harvie Ward that drew 10,000 spectators, but by the late 1960s Harding was deemed no longer suitable as a tour stop. The pipeline of good young players had run dry, and the course was spiraling slowly into utter disrepair.

Still, Tatum and Harding had bonded before Tracy met Hepburn. Tatum, who grew up affluent in Los Angeles, had first played Harding Park in the 1939 San Francisco City Golf Championship when he was a member of both the golf and debate teams at Stanford, for whom he would win the 1942 NCAA individual golf championship. He would go on to play in the tournament some 40 more times and, though he never won, he came to feel much the same way about Harding as he did his favorite golf shrine, the Old Course at St. Andrews.

"The quality of the place just fixed in my being," intoned Tatum recently while standing on the back tee of the newly stretched and strengthened 470-yard par-4 18th at Harding, bundled in cashmere and poplin, and his eyes watery but bright. "As the years passed and the condition got worse, I still saw it -- what I thought it should be. Then in early 1997, I simply decided, 'I'm going to try to do something about this.' "

And so, after a circuitous and sometimes interminable ride, Tatum's vision has become Harding Park's $16-million renovation. When it reopens around Labor Day after being closed for 17 months, it will surely draw raves for its retained character, suddenly superb conditioning and majestic but traditional challenge. At its new full length of about 7,250 yards and par 70 (it will play as a 6,800-yard par 72 from the men's tees), including 18 new greens and nearly as many tees, Harding specifically was designed to stage a major PGA Tour event every three years, most likely the WGC-American Express Championship beginning in 2006. By that time, odds are Harding will have surpassed Torrey Pines South and Bethpage Black as the finest publicly administrated golf course in the land.

Harding, designed by Willie Watson in 1925, is built on the same sand-dune region on the western fringe of San Francisco that Alister Mackenzie in the 1920s called "the finest golfing territory I have seen in America." Adjoined by the Olympic Club and the A.W. Tillinghast masterpiece at the San Francisco GC, it is actually on a better piece of property than either one -- a gently rolling bluff surrounded on three sides by Lake Merced. "Most of the top players of my era thought Harding was the best layout in the city," says Venturi, whose father, Fred, served as the head pro at the course for many years, and who won his last PGA Tour event at Harding in the 1966 Lucky International.

"It was easy to see it could be something great," says Chris Gray, the PGA Tour's lead course architect. "We added some strategy and some length [about 400 yards] to accommodate the modern game, but basically we just had to bring it back to life. To me, it's a little utopia of golf." Tatum, who for the last several months has been giving tours of the course, says, "I get at least two 'wows' a hole."

Completing the project will be a First Tee facility, a fully renovated nine-hole "inner" course geared to less advanced players, and a more spacious driving range. A new clubhouse overlooking Lake Merced is due by next year. For even nongolfing San Franciscans, Harding Park's ascendancy is gratifying in the way of doing right by an old friend. "We have some jewels in our city, and Harding Park was always one of them," says city supervisor Tony Hall, a nongolfer who was the chief political muscle behind the renovation. "It's just that for the last 30 years, we forgot about her."

The man who reminded San Francisco of what it had was Tatum. By fully accessing his connections, his acumen and -- most of all -- his passion, he became the right man at the right time in the right place, with the right idea.

"People responded to Sandy," says deputy city attorney Michael Cohen. "At public hearings, which can be so contentious, people would listen to Sandy's presentation and stand up and cheer. Because of the dignity with which he conducted himself, and because he has no vested interest in the project, they intuitively trusted him. It was an example of public service on the highest level. He is an uncommon man from an era you hope desperately is not gone forever." Adds Phil Havlicek, president of the Harding Park Golf Club: "People have been talking about saving Harding Park for the last 20 years. But it just seemed too tough to stick it out. Sandy was committed like no one has ever been. He was our angel walking down the fairway."

For all the celestial overtones, the art of the deal that transformed Harding Park was founded in hardball politics. In what Cohen calls San Francisco's "massively participatory democracy," Tatum's challenge was to make golf relevant in a diverse city during a time of economic shortfalls and budget cuts. "The problems of the homeless, crime, public transportation -- those things get government people's attention," he says. "But not golf."

Tatum started fastening nuts and bolts behind the scenes. He began by piquing PGA Tour commissioner Tim Finchem's interest in Harding, playing on the tour's pent-up desire to make San Francisco a regular stop on a feasible venue. He then got Mayor Willie Brown's qualified support for the renovation, especially by selling the social significance of The First Tee. Arnold Palmer's golf-course management group then came into the picture, negotiating a package that would have given them control of Harding in a 35-year lease arrangement.

What emerged was a Rubik's cube of special interests. The city unions -- and, by extension, the politicians -- wanted to ensure that civil servants would continue to maintain the course, while the tour and the Palmer group preferred private workers who would cost less and be better trained. Meanwhile, the city's public golfers -- and especially senior players -- wanted green fees to stay in the same range (about $20) they already were paying.

The project languished in negotiation for more than a year until 2000, when the Palmer group decided not to take the lease. Another year of inactivity followed, with the project to save Harding seemingly dead. "It was discouraging, but in many ways it was the best thing that could have happened," recalls Cohen. "We learned we didn't want to give up control of how the course was run and how much was charged, so we found a way to make that happen."

The breakthrough came in 2001 when the city recreation and parks department secured a $16-million grant from the state recreation and open space fund, and then found a way to apply it to Harding. Because using the money for a public golf course was not in the "hierarchy of need," Cohen devised a plan in which the money would be used as a loan that Harding, through its profits, would pay back. "The net cost to the city will be zero," he says.

Since San Francisco's 11 supervisors each represent different areas of the city, at first each wanted the money to be used in their district. That's when Hall, a wedding singer by profession whose district contains Harding, made a convincing case that the project -- especially bringing a major golf tournament to San Francisco's suddenly high-profile public course -- would bring income and image enhancement to the project and the entire city.

Debate was hot, with most opposition coming from a group called The Friends of Muny Golf. Finally, in March 2002, the project -- with conditions including The First Tee, city workers, a tour event every three years, administration by KemperGolf Management and a first-ever city golf fund to keep money coming back into the course rather than the city's general fund -- passed 11-0. "It's probably impossible in San Francisco to pull off a project that satisfies everyone," says Cohen, "but this was pretty darn close."

Still, the equation is delicate. For San Francisco to make its $4.3-million yearly overhead for Harding's employees and equipment, the course will have to generate about 80,000 rounds in a multitiered green-fee structure. About 65 percent of the play is expected to come from San Francisco residents, at an average of about $28 per round. Nonresidents will play about 20 percent of rounds at approximately $75 a pop. The remaining 15 percent of players are expected to come through the city's hotel-purchased starting times at more than $100 a round. The key to the course's allure is the continued presence of the tour which, every year a tournament is held at Harding, would be contractually obliged to kick in $1 million in proceeds to the city golf fund.

For the tour, the vital issue is that the golf course be maintained at a level suitable to holding a world-class event. Harding's history of neglect has led to a lot of skepticism with the city workers now charged with doing the job. Indeed, the tour can get out of the contract if maintenance is deemed inadequate.

Officials insist the problem was resources. "The old Harding was understaffed, under-equipped and underfunded," says Sean Sweeney, the city's director of golf. "We've never had the chance to succeed before."

Now they will, and the tour is on board. Sweeney's staff has been increased from 14 to 26, and $1.2 million has been spent on new maintenance equipment. KemperGolf, which manages courses in municipalities such as Chicago, Kansas City and New Orleans, will provide additional worker training. Moreover, there will be oversight from the USGA agronomist and the tour. If the city workers fail, there is a contingency for private workers to take over.

"It could go bad, but I just don't see that happening," says Steve Skinner, president of KemperGolf. "There is too much momentum going the other way. Besides, the whole world is watching."

To Tatum, therein lies opportunity. "I really hope what has happened in San Francisco has universal application," he says. "I hope the combination of Bethpage and Torrey Pines, and now Harding, re-ignites and stimulates interest in public golf, as played by public golfers on truly public golf courses. I've always hoped it would, and I really think it does."

Now Tatum is rolling, a self-described True Believer in the True Game preaching the gospel of his life.

"What's achieved is an asset for the community," he says. "Playing golf has all kinds of wonderful benefits for people, particularly on a quality golf course. And that's such a vital factor in what we've been able to accomplish here. We are giving these people something they can treasure and will matter immeasurably in their lives. Golf is anything but trivial. As the problems in the world become more terrible, this game is more important -- on a sociological basis -- than it has ever been. It's a life enhancer and a life extender. There's no question about that. It has everything that you can add from a game to somebody's life."

Tatum could be Exhibit A, and as he walks Harding pointing out its "minimalist delights," his satisfaction is clear. For all his self-effacement for his role in the project ("There is something to be said for having an ability to identify values and articulate why they matter," he says), Tatum also admits he considers what has transpired at Harding the crowning achievement of his life. "It's the best thing I've ever done," he says.

Not that he's finished. With future monies from the city's golf fund, Tatum wants to spearhead an effort to similarly "fix" San Francisco's two other notable public courses, Lincoln Park, a 5,416-yard jewel that weaves past the palatial Legion of Honor Museum to spectacular views of the Golden Gate Bridge, and Sharp Park, a Mackenzie design on the city's southernmost coast. "I want San Francisco, which was a golf paradise and then paradise lost, to be paradise regained," he says. The ultimate dream -- though he dares not say the words himself -- would be a U.S. Open at Harding Park.

Of course, Tatum has to last long enough to see it, and to that end he has increased his exercise regimen. "I'm not going to give in to being an old man," he says. "It will happen, but I'm not there yet. I think I'm in upper middle age, and that helps me."

Adding that he "refuses to accept shooting my age as an accomplishment," Tatum might be testing his 6.5 index a little more frequently, now that Harding is back on his personal rota.

"Sure, I'm going to play Harding," he says. "What I really look forward to is the first City Championship after all the work. It will again be a premier amateur event. God, I loved playing in The City. And maybe I'll play again."

He may never win the championship. But for Tatum, rescuing its venue -- and the soul of public golf in his hometown -- may be a legacy better than any trophy.