News

Thoughts From Bethpage

saturation point: A small army of Bethpage workers cleared water off the low-lying 18th fairway with squeegees Thursday after heavy rain forced first-round play to be suspended.

Lucas Glover won the 109th U.S. Open, but Craig Currier was a close second. Ricky Barnes, David Duval and Phil Mickelson, of course, shared runner-up honors in the championship, but without the Herculean efforts of the Bethpage State Park superintendent, his staff and scores of volunteers whose idea of a good time was getting the Black course playable after relentless rain—with everything from squeegees to supersize syringes that drew standing water out of the cups—the medals would still be in a drawer somewhere.

There must have been some four-leaf clovers in all that rough the USGA has grown over the years. How else to explain that this was only the third U.S. Open so plagued by bad weather that an extra day was needed for regulation play to be completed? "The U.S. Open is a long week when everything goes perfectly," said 2006 champion Geoff Ogilvy during a week that stretched into Monday with more starts and stops than the relationship of a pair of fickle teenagers. "We even got lucky [Sunday]," said Currier, who arrived at the course about 3 a.m. every day. "All around us it was pouring. But the weather [overall] was about as bad as I can imagine."

It was the first extended U.S. Open since 1983 (playoff years not included), when a storm late in the fourth round at Oakmont CC forced the last few groups to complete play Monday morning, and Larry Nelson ran in a 60-foot birdie putt on the 16th hole to edge Tom Watson. The only other weather-lengthened Open was won by Billy Casper at Winged Foot GC in 1959. That year severe weather on the scheduled 36-hole Saturday conclusion (U.S. Open practice until 1965) allowed only the third round to be completed, bumping the fourth round to Sunday afternoon—mid-afternoon, in fact, thanks to a New York law that prohibited sporting events from commencing before 2 p.m.

The meteorological curve balls at Bethpage—which stopped play for the day after less than four hours Thursday morning and again late Saturday, a suspension that lasted until almost noon Sunday—were harder on some than others. Specifically, the half of the field that had early/late starting times the first two rounds endured much tougher conditions and averaged nearly two strokes higher (74.76 versus 72.87) in the first round compared to golfers on the other side of the draw. "It's not much fun when you've shot what you thought was a good 72 and you think 69 is leading, and all of a sudden, you know, it's like throwing darts out there," said Lee Westwood.

Bethpage had been softened by second-day rains during the 2002 Open, but this year's precipitation had an even greater effect on the venerable muny. Relatively short-hitting Mike Weir flirted with tying the all-time major scoring record (63) with an opening 64. Hybrid and long-iron approaches were common throughout the championship, but the soggy greens held any kind of shot. "I hit a 4-iron today on No. 7 that was about head-high and only [released] about 10 feet on the green," Tiger Woods said after the third round. "I don't think I've ever seen that in a U.S. Open. It's just different. It's more like what we face week-in and week-out. Certainly not the U.S. Open."

Architect Rees Jones, who renovated the Black course before the '02 Open, wondered if covering the greens with tarps to keep rain from softening them was the solution. "I would love to see them use tarps," said Jones, whose dad, Robert Trent Jones Sr., had encouraged the USGA to use fairway gallery ropes for the first time in the 1954 Open at Baltusrol so the rough wouldn't get tamped down by spectators. "The greens would be in the same condition for every player in the field. Now that Opens are so big, maybe we could do it. It would be a big undertaking, but it might take less time to put the tarp on and off than it does to squeegee them. I'd like to protect the setup like my father did in 1954."

"We talked about it in 2002," Currier said. "If you knew you were going to have a heavy rainfall at night, it might be something you could try. But we got caught in a couple of downpours [during play] this week—we wouldn't have had time to get tarps on them, and it really wouldn't have mattered."

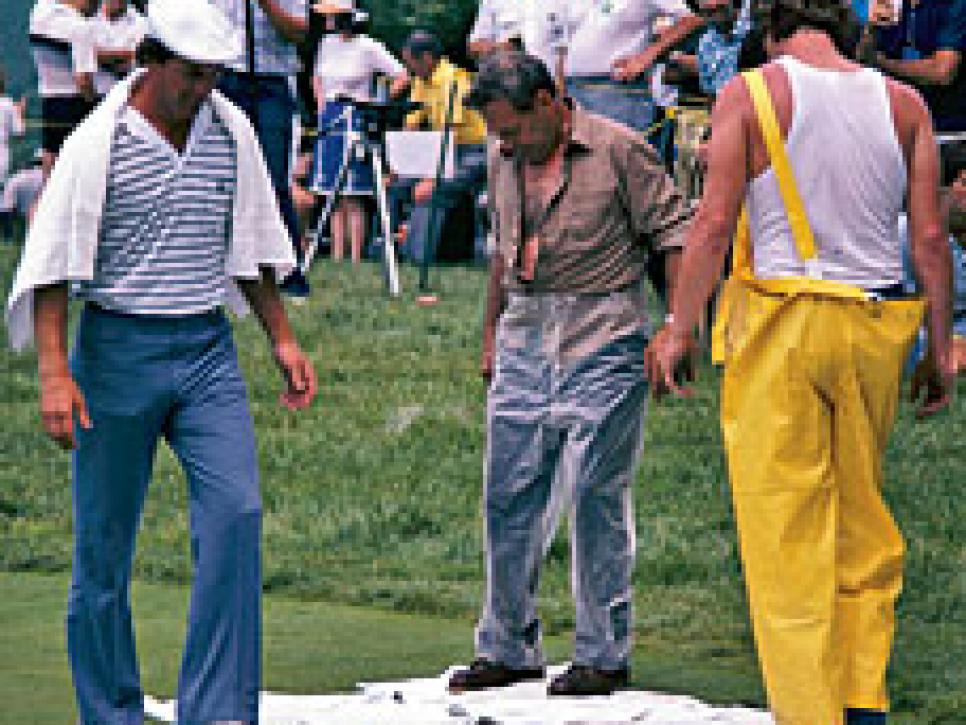

There would be no way to shield the rest of the course from moisture, the most vulnerable spot being the clay-soiled valley containing the 18th fairway, which required the most attention—squeegeeing, rolling and pumping the water out of the area. "The greenkeepers did a truly unbelievable job," said Ross Fisher, who finished fifth. Still, balls sometimes picked up mud in the fairway, and the USGA was adamant about not allowing lift, clean and place—which retired USGA rules and competitions director Tom Meeks at the 1996 U.S. Open derisively referred to as "lift, clean and cheat." As USGA championship committee chairman Jim Hyler reiterated before the championship: "If it's not fair to be playing the ball as it lies, we'll suspend play."

The PGA Tour allows improved lies as a last resort to get tournaments completed. "I think it's great they're playing the ball down," said Mark Russell, a vice president of rules, competitions and administration for the tour. Agronomic conditions are so much better now than they used to be, the unpredictable shots that come from mud on the ball don't occur as often. "I'm looking at that beautiful grass right now," said 80-year-old former Masters winner Bob Goalby over the phone as he watched the third round on television. "Normally we had half grass, half dirt [surfaces], and you picked up a lot more mud than they do now. We played with a lot of mud on the ball. It was kind of a crap shoot. You'd hope the mud would be knocked off as soon as you hit it. Most of the time, it came off. But once in awhile, if it was really gumbo, if it really stuck on there, it would make the ball nosedive or veer to the left or right."

Goalby never tried to apply the conventional wisdom that if mud was on the left side of a ball, it would cause it to fly to the right, and if it was on the right, it would cause it to curve left. Woods, who lamented the four "mud balls" he had during a first-round 74, tried to apply the theory on one of them without success. "The one on 16, the mud was on the left side," Woods said, "and you know obviously it goes right, so I tried to put a draw on it, and it turned into a slice, so that really didn't work out."

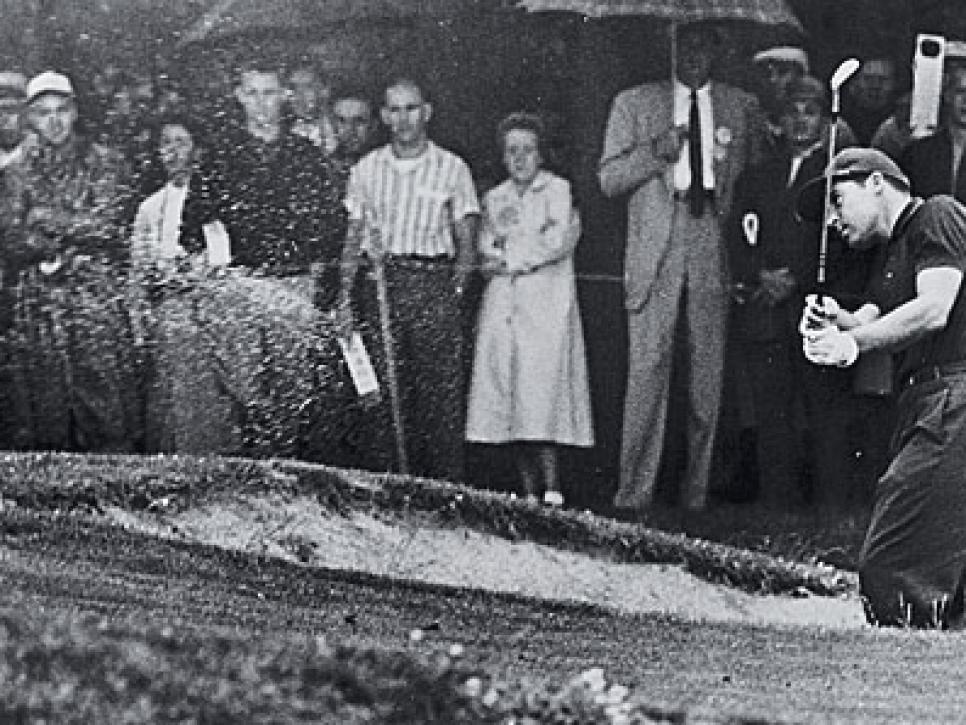

Today's players can be glad they came along when they did. While they had to deal with "the pot luck" from the fairway (as Woods called it), before a revision of Rule 35-1d in 1960, a ball couldn't be cleaned on the green. This caused a whole other set of frustrations, as former tour pro Jackson Bradley experienced in the 1958 U.S. Open and recalled to Austin Golf magazine in 2004. "I had a pretty fair round going, and I was a cinch to make it to the weekend," Bradley said. "On the 13th hole … they'd syringed the greens, and my ball was covered in mud. I four-putted from six feet below the hole. I was furious. I walked over into the rough where John Winters and Joe Dey, who was the executive secretary of the USGA, were standing. I took the muddy ball and ground it into Joe Dey's palm and used very bad language on him. In so many words, I expressed my interest in changing the rule."

After his second consecutive T-6 at a major—the Masters in the sun, the U.S. Open in the slop—Woods is interested in changing his fortunes on the greens. He had an inconsistent putting performance at Augusta National and again in the Open, struggling with the pace of his putts, normally a strength. It negated an excellent long game that approached the way he struck the ball in winning at Bethpage in 2002.

"My good ones aren't going in, and my bad ones aren't even close," Woods said. "[The greens are] a little bit slow and bumpy, but you have to be committed to hitting it that hard, and I left a lot of putts short. And then when I tried to hit it harder, I gunned it past the hole. Overall, I gave myself so many chances and made nothing."

Woods had only one three-putt but missed some 20 putts inside 15 feet over 72 holes, including six in a final-round 69. One of Woods' most costly misses was a four-footer for bogey on the 459-yard 15th hole in the first round, when he played the last four holes four over, equaling the second-worst such stretch of his PGA Tour career. "If you can play it at 16 [strokes] for the week, that's a great score," Woods said of No. 15. Instead he played the most difficult hole of the Open (4.4699 average) in 20 strokes, and the four shots turned out to be the margin he finished behind Glover. Of course, Woods also could point to bogeys on his finishing hole the first two rounds, maddeningly similar to the way he bogeyed the 18th at the Masters in three rounds.

His 74-69 start left him 11 strokes behind Ricky Barnes' record-setting 36-hole pace. It turns out Woods would have needed to tie Larry Nelson's record closing 36 holes (65-67 at Oakmont in 1983) to finish at five-under 275 and win outright. An 11-stroke comeback also would have equaled the largest in U.S. Open history, established by Lou Graham in 1975 at Medinah CC when he tied John Mahaffey, then defeated him in a playoff.

That Woods narrowed what had grown to a 14-shot deficit after 45 holes was of little consolation to him. Although he has earned nearly a third of his 64 PGA Tour stroke-play victories coming from behind after three rounds (including wins this year at the Arnold Palmer Invitational and the Memorial), he hasn't done so in a major, and he trailed by nine after 54 holes at Bethpage—too steep a climb even for someone so familiar with the summit.

There was little good karma in the moist Long Island air for being the defending U.S. Open champion, either. Only six people (Willie Anderson, Johnny McDermott, Bobby Jones, Ralph Guldahl, Ben Hogan and Curtis Strange) have won consecutive championships. Woods has fared better than most defending champs in the last two decades. Since Hale Irwin's T-11 in 1991, Woods and Retief Goosen are the only defenders to finish better than 40th in their title defense.

But when you traffic in domination the way Woods does, a top-10, even at a major, is devalued currency. His mood seemed about as dreary as the skies that had given the U.S. Open fits, his mind more on the 120 putts he had taken than the $233,350 he had won.

.jpg)