I Died And Came Back A Golfer

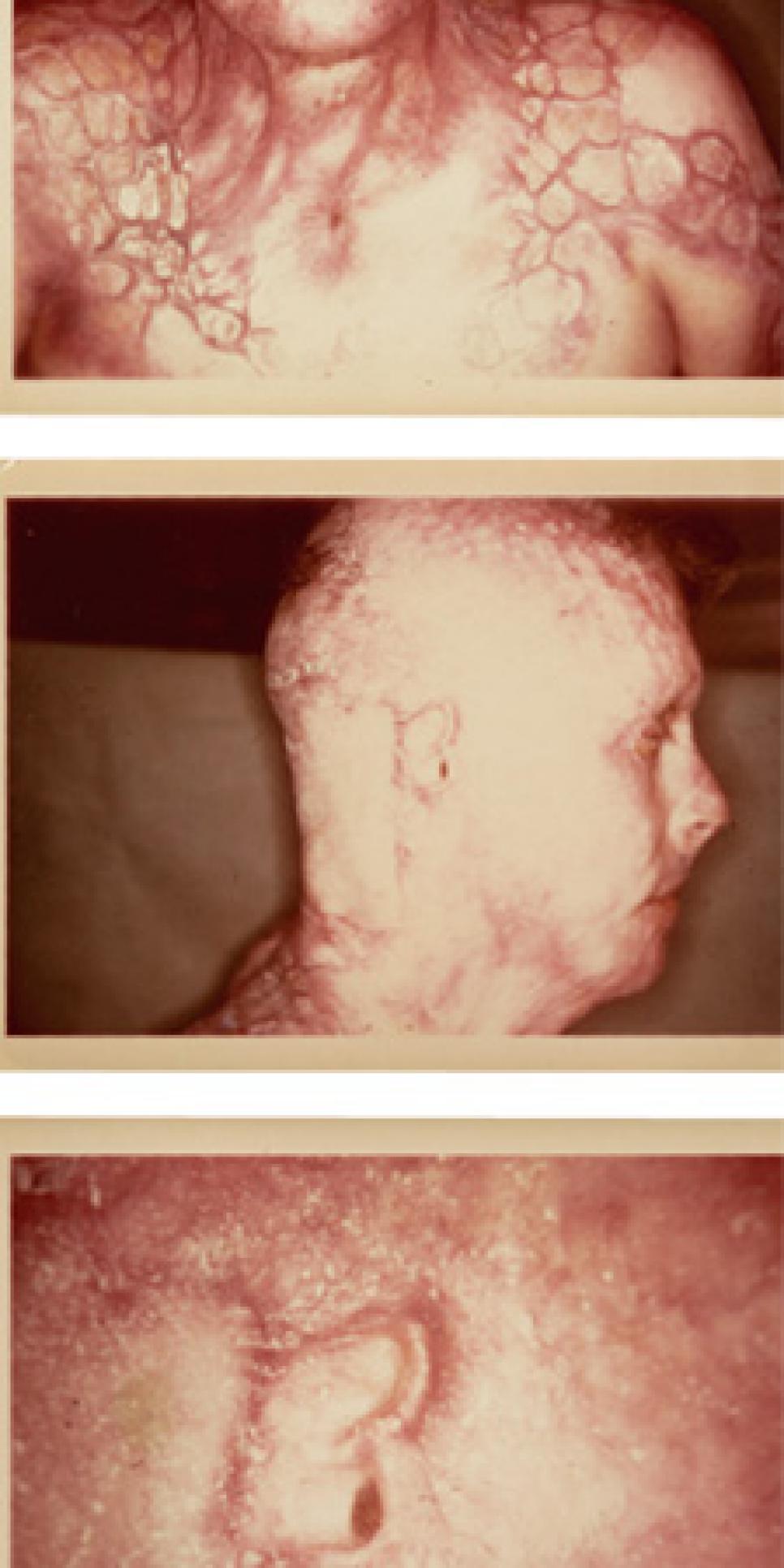

Sam LoCicero suffered severe burns and was nursed to health by his wife, Marian.

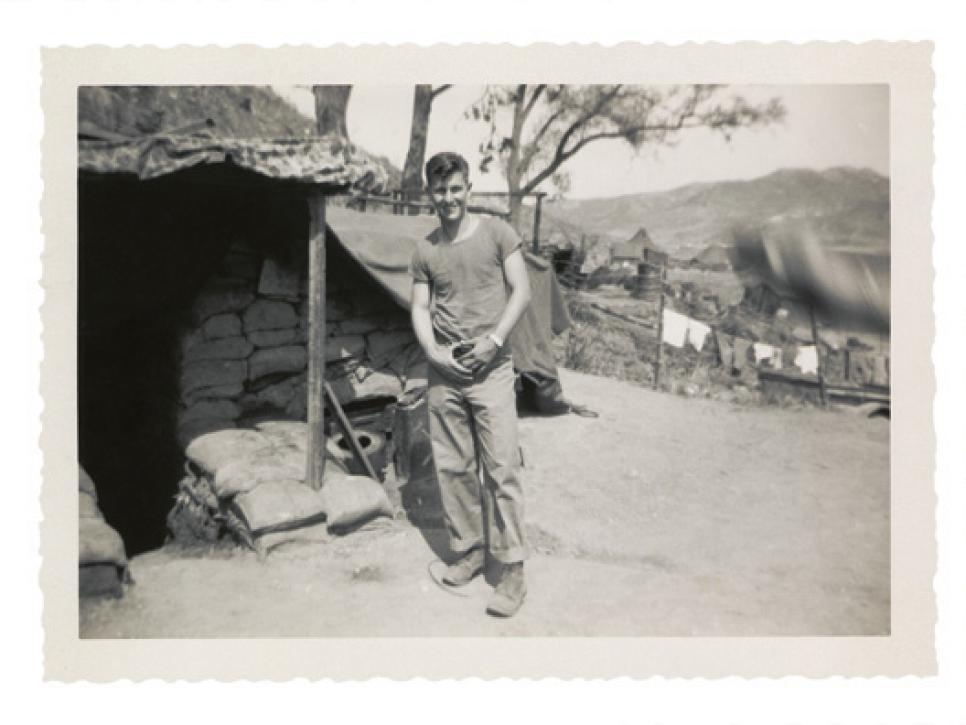

When I got home after 11 months fighting in Korea, some friends took me rabbit hunting. The dogs flushed a little bunny right to my feet, but I didn't shoot. My friends laughed and called me a sissy. As a Marine I had shot at men, but I wouldn't shoot something so small. I found a guy who traded me a rusty set of golf clubs for my shotgun, even up. I had always wanted to play golf, but growing up the son of a bus driver, it had never happened.

For my 27th birthday my beautiful bride, Marian, bought me a new set of clubs from Sears, Roebuck. I chipped around in the yard, but I never took them to the course because only nine days later I suffered the accident that nearly ended my life. It actually did kill me -- at one point I was pronounced dead long enough for a doctor to deliver the news to my family in the waiting room -- but more on that later.

It was 1959. I was working as an electrician for General Electric, which was building a plant near Freeport Sulphur Heliport in Louisiana. An electric panel the size of a house was smoking, and there was just enough space for me to slide underneath on my back to check it out. I didn't want to, but the head engineer insisted someone must, and I didn't want my older co-worker to do it.

I saw right away what was causing the smoke. Whoever had painted the panel had done a sloppy job and let paint dry onto the electric points. The only thing to do was let it burn off. As I went to slip out, my back arched just a little too much and 13,800 volts hit me.

They say I was stuck to that panel for three minutes. A guy ran 150 yards and back to get rope to loop around my feet and pull me out. My face was sizzling on the panel, and my shirt was on fire, and I remember thinking, Oh man, I'm dead. The next thing I recall was waking up in the backseat of a car on the way to the hospital. There was no ambulance, but we had policemen on motorcycles running relays to hold the traffic at intersections. The smell was terrible. In Korea I'd smelled bodies burned from napalm, and it's a smell you never get out of your nose.

In the hospital I was blind. My body was the color of charcoal, and a white film covered my eyes. I asked for my wife, and when they said she was in the room, I said, "Kiss me, Marian." I could hear the nurses urging her not to for risk of infection. But then I felt her lips plant onto mine. She whispered that she'd never leave me. If she hadn't kissed me then, I think I would've died within the hour.

accident, in 1964. (Courtesy of Sam LoCicero)

I spent the next year in the hospital. My leather belt and thick blue jeans had protected my body from the waist down, and so the doctors used the skin from my legs to perform multiple grafts. This was torture, and I don't know the words to express the pain. The worst part of each day was sitting in the whirlpool bath while they scraped the dead tissue. Five months into this I had my first facial plastic surgery. There was a complication with the anesthesia, and this was when I died. I know it's what everybody says, but I saw a light. Everything was peaceful, and I was lifted up to the light. When I got through it, there were three clear, floating beings, like jellyfish, and the biggest one, which was dark, enveloped me. Then it released me, and I rushed back down and woke up on the operating table. I saw my chest was open, and the doctors had my heart in their hands, pumping it.

I've never been a religious man. But if you don't think there's something up there, think again.

With the exception of visits to doctors and surgeons, during the next six years I didn't leave my house. We took down all the mirrors. Every once in a while I'd catch a reflection in the blade of a butter knife, and that was enough. Once we went to a drive-in movie, and I draped a sheet over my head. I remember a group of sailors pointing and yelling into our window. I did have one friend who would come over and play chess. Fortunately, during this time Marian and I were able to have our two boys, Dabney (Duke) and Vincent (named for the doctors who saved my life: Dabney Ewin and Richard Vincent). Because I was always around, neither one of my boys ever suffered a wet diaper long, let me tell you.

From our settlement we had what we needed, but we weren't rich. There were several uncertainties surrounding the medical bills, and our lawyers had been scared to push too hard against GE. We received about $120,000 in 1960s dollars.

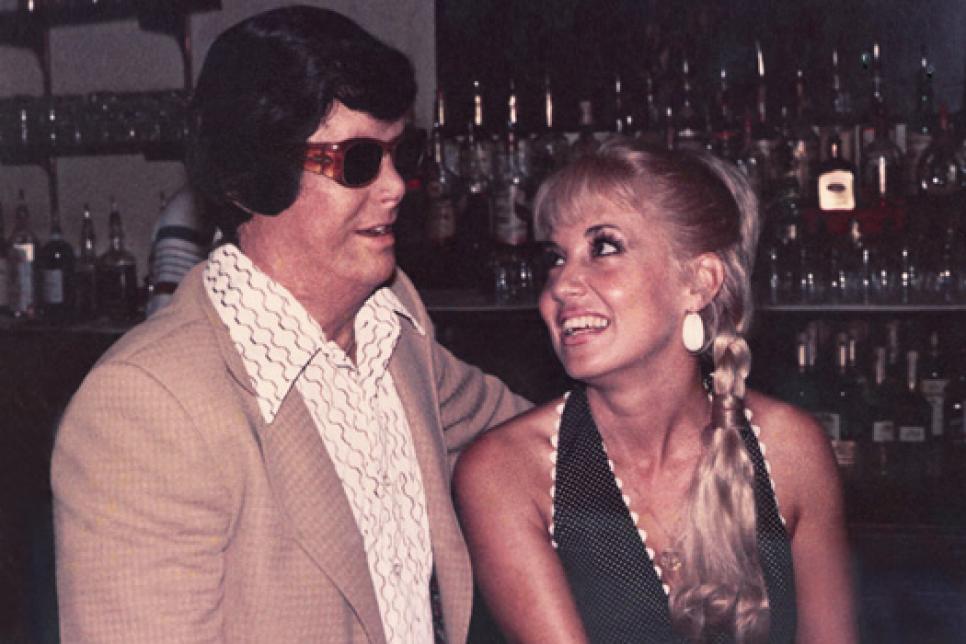

My face came along. My nose was built, and I got ears that affix with glue. (I've been using the same brand of glue for 40 years, and they've never come off at the wrong time!) Marian would do my wig and makeup, and I started working out with dumbbells. I built myself up to 160 pounds from the 86 I had been in the hospital. (Before the accident I was 140.) When Dr. Vincent died, Marian said I looked good enough for her and that I shouldn't suffer through any more plastic surgeries unless I wanted to. I didn't.

With scar tissue on 95 percent of my body I have almost no sweat pores. So there was a lot of concern the first time my brother-in-law and his friend decided to take me to play golf. It was a hot, humid day, and I wore sunglasses, long sleeves and a hunting cap with earflaps to protect me from the sun. But I was excited. I'd been watching Jack Nicklaus start to win majors, and I'd been practicing my swing in the yard with my decade-old yet still brand-new birthday present.

That day at Alvin Callender Field, the course at the joint reserve base, I didn't get the ball airborne more than 50 yards. Even though I was strong, my grafted skin was tight. But man, watching the ball fly 50 yards felt great after being holed up so long. It felt good, really good, just to hit something. I told my new doctors, some of whom were golfers, that I was hooked, but they cautioned me to have realistic expectations.

I kept playing. Sam Grimes and Perry LeBlanc were good about taking me regularly. At home I swung a baseball bat -- shorter than a golf club -- to avoid marking the ceiling. My uncle made me a wheel with a handle that I turned to rip the skin that was fusing my left armpit to my left side. It would bleed and fuse back, and I'd have to rip it again, but over time it freed my arm.

I developed a compact swing and a good short game. I played my best golf in my 50s when I was a 5-handicap. I've shot even par three times in my life, made a hole-in-one, and in 1981 I was runner-up in the first flight of the club championship at Ormond Country Club. I talked a lot of trash, and none of my golf buddies liked losing to me.

The competitiveness of golf, combined with the therapeutic loosening effect the swing had on my skin, falls short only to Marian when it comes to saving my life. Golf gave me a reason to rehabilitate and the confidence to overcome the self-consciousness of being disfigured. On July 20 I'll be 79 years old. I haven't been playing much lately because of nerve damage in my legs, but I still putt and chip at the range. I remain positive that I'll be playing again soon.

Top: Sam in Korea in 1951. Bottom: Sam and Marian at a party in New Orleans in 1981. (Courtesy of Sam Locicero)