"We're Probably a Little Sick"

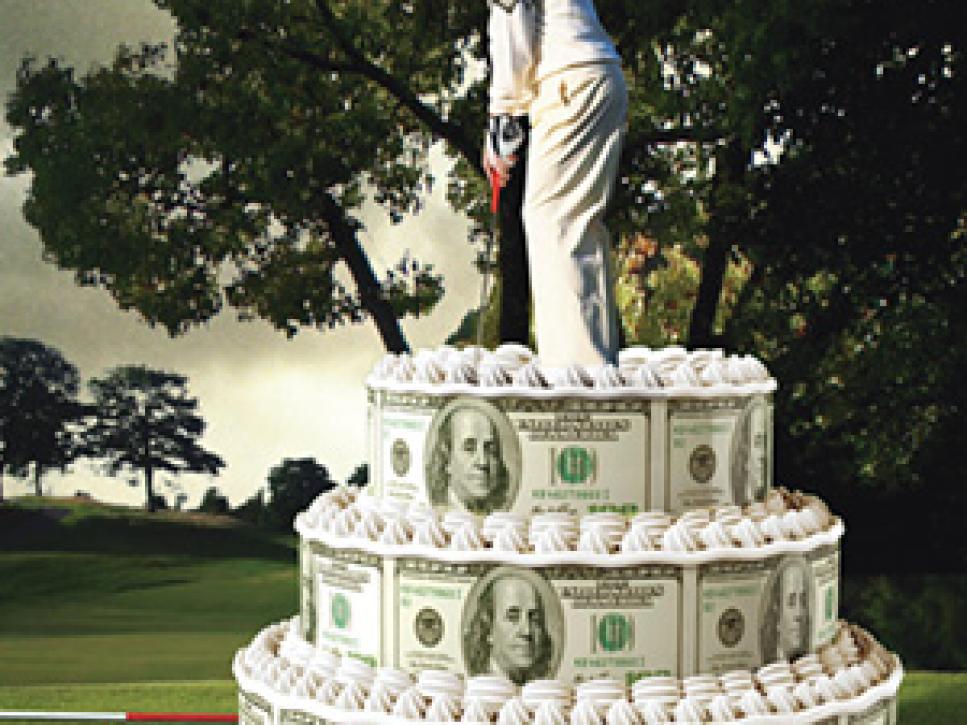

If you're going to play golf with Eddie and his group, you'll need lots of money and some serious cajones. Though many of us like to have a little something riding on a match—maybe a round of drinks in the clubhouse or a $10 nassau to keep things interesting—for Eddie's crew, gambling is something else altogether. Playing at a top country club in Southern California, guys who make up this loose-knit network of 20 or so serious amateur golfers routinely risk as much as $10,000 per man over 18 holes. When a professional athlete or high-roller from Vegas slips into town, wagers can slide into the $40,000-per-round range. As one of the gang puts it over a clubhouse breakfast: "We're probably a little sick.

But we're a different breed of people. We like to have cake in the game."

Roughly 80 percent of male golfers 18 and up gamble when they play, according to a 2013 Golf Digest survey. It's both pervasive and, in most cases, relatively benign, says Lia Nower, professor and director of the Center for Gambling Studies at Rutgers University. "For 99 percent of the people, it's a way to spice up their game. I speculate that because it's an individual sport and you gamble on your own performance, it will make you play better. It can be motivating."

Generally the stakes are small. In a research paper published in 2001 by the scholarly journal International Gambling Studies, only 5 percent of golf gamblers reported risking $200 or more per round. (A separate study by Starwood Hotels & Resorts found that 87 percent of CEOs gamble at golf, and they wager an average of $589 per outing.) Even the United States Golf Association "does not object to informal gambling or wagering among individual golfers or teams of golfers when the players in general know each other," according to the USGA's Rules of Amateur Status.

The USGA goes on to say that when gambling, the stakes must not be "generally considered excessive." Eddie and his regular crew fail that test. Partly for that reason, but mainly because they have day jobs and they don't want to attract hustlers or the IRS, Eddie and friends have insisted on using pseudonyms.

Besides, they already draw enough negative attention at their club. "People here look at us like we're derelicts," says James, a buddy of Eddie's. "We're the unwashed and, sometimes, the unwanted. But I wouldn't have it any other way. Country clubs are supposed to be reserved and cultured. That's bull----. My idea of a club is four guys going out onto the golf course for four hours and battling over $100 bills."

The club where they play most often, which Golf Digest agreed not to name, declined to comment on Eddie and his friends.

A $10,000 SWING IN ONE SHOT

Riding out to the first tee, Eddie explains that he does not play golf to relax. He thrives on the pressure that comes with high-stakes betting and every stroke counting. The founder of a successful company and in his early 50s, Eddie says he likes to test his skill, his mettle, his ability to keep from unraveling under big-money pressure. "I've had countless situations with 10-footers on the 18th where sinking it means the difference between winning $5,000 and losing $5,000," he says. "That's a $10,000 swing in just one shot! People on the practice green fantasize about putting for a U.S. Open win. We have situations like that all the time. The pressure is on, and something serious is at stake."

Eddie and his golf cronies are all wealthy guys: doctors, CPAs, attorneys and entrepreneurs. They travel extensively, visiting courses such as Shadow Creek, Pebble Beach, Pinehurst, Oakmont and a club in the California desert. At that club, "there's always action,"Eddie practically purrs. (The club in the desert had no comment. The other clubs and courses did not respond to our request for a comment.) The players gamble among themselves, take trips specifically to wager with others, and, five or six times per year, participate in gamblers' golf tournaments. Entry fees are around $7,500, with the money distributed to various winners. "If you play really well, you might be able to win $20,000 from the pool of cash," Eddie says. "But more than that's at stake in the wagering that gets done on the course."

Today's proceedings in Southern California are a bit tame—at least for this crowd. The group is 16 players, and a complex skein of nassaus, automatic presses, team bets, low-score wagers and birdie bonuses promises to provide the necessary pressure. There is also a penalty for shooting above your handicap: $25 per stroke, paid to each participant, so it's $375 if there are 15 other players. This provides one more way to gamble and serves as a preventive measure against sandbagging in future rounds.

that when you do lose, you feel it.'

To juice things up a bit, Eddie suggests that his foursome engage in bridge bets. These are wagers in which two players commit to making a certain combined score for a particular hole. The payoff is based on how many strokes above or below that number they wind up with. On the first two holes, it does not work out so well for Eddie and his partner, Phil, a dour, profanity-spewing executive with a cigar clamped between his teeth. Their opponents want to do it for $800 on the third, but Phil wants to bet only $200. Without hesitating Eddie says, "I'll take the $600."

The hole is a par 4, and Eddie's opponents wager on making a combined score of 8 (they are both close to scratch golfers). The first guy's drive takes a lucky bounce off a bunker, and after a good approach, he has a putt for birdie. Eddie flubs his shot but doesn't really care. All his attention is on his opponents making bogey or worse. One guy makes birdie, the other makes a par, and Eddie has dropped a quick $600 on seven swings of a golf club. It's only the third hole, and he's already down $800 in side bets, but none of this sours his mood. Maybe he takes some consolation in the knowledge that it won't end as badly as it did for one newcomer to the game. Playing on a typical Saturday morning, this guy got carried away with a variety of bets, didn't handle the pressure very well, and needed to retrieve $36,000 in cash from the trunk of his car to pay off his opponents.

By the end of today's round, the wins and losses will come to around $2,000 per player, the results tallied over beers with a level of seriousness and cross-checking that suits the stakes. Relatively speaking, it's small potatoes. But, considering that these guys play four or five days per week, the money can add up.

"We gamble for enough that you can lose $10,000 in a week—and the club is closed on Mondays," says Phil, passing a four-figure check across the table. "Nobody wants to do that. But, on the other hand, you want enough money at stake so that when you do lose, you feel it. It gets your attention and keeps your blood flowing."

AMPING UP THE ADRENALINE

For Eddie, it's a reason to tee it up in the first place. During his early 20s he played in a competitive after-work basketball league. When his knees blew out, he needed to find another sport, and golf looked like a good one. But he found his 18-hole outings lacking in adrenaline production—until he had something riding on his play. The action gave him the incentive to become a 5-handicap golfer. It's also endowed him with cachet as a clutch specialist, the kind of guy who might botch the front nine and dig deep to make it all up on the back. "Let's say you get two guys who have the same ability, and there's money on the round," Phil says. "Eddie is the guy I'll want to bet on." Adds a fellow who has partnered with him and played against him: "Eddie makes 15-foot putts until people's eyes bleed. He'll make 15 pars in a round, and that puts the pressure on anyone who's trying to beat him."

This manifested itself not long ago on the 18th hole at Shadow Creek, where Eddie was down $3,000 on the round. With $2,000 worth of bets riding on the hole, tying it would have cost him $3,000 overall, losing would have cost him $5,000, and winning would have cost him $1,000 on the round. "I called for an aloha—it's our slang for adding an extra bet on winning the hole—in this, case $500," Eddie says. "My partner didn't want it because things had been going so badly for us.

Gambler that I am, I took both sides," meaning that Eddie bet an extra $500 on him winning the hole and $500 on his partner winning it. "I made a birdie with a 20-foot putt, my partner won the hole, and I managed to break even instead of losing $3,000," Eddie says. "That one totally felt like a win. The stress of needing to do it is what gambling golf junkies live for. If I don't have the feeling that I need to win the hole, it's just not any fun for me. Yes, there's plenty of tension, but it's good tension."

That said, he finishes his post-round beer and heads off to play in a pricey gin game that usually follows mornings of golf.

KID POKER TRIES GOLF

Back in the early 2000s, when Eddie was just starting to take golf seriously, Daniel Negreanu established himself as one of the top no-limit Texas Hold 'em players in the world. It earned him a nickname: Kid Poker. Soon after, when online poker began to flourish and the game's top players had money to burn, he decided to join his high-stakes pals on the golf course. Negreanu, now 40, immediately discovered that his nickname was nontransferable. Playing golf against the likes of Doyle Brunson and the late Chip Reese, well-known as astute poker players, "I should have known I was in trouble," he says. "They offered me a certain number of strokes, and I agreed. Later, I found out that they had never seen anything like that. Nobody just agrees. Usually there's a ton of haggling. My first day out, I lost $550,000. Mike Sexton [co-host of World Poker Tour telecasts] was the third guy I played with. He was supposed to be a bogey-shooter and shot 75. Like everybody else, Mike told me that he shot the best round of his life when he played against me."

Brunson remembers the day. "I thought it was fair," he says. "I was playing on one leg and had to use a crutch to get to the ball." Adds Sexton: "Daniel thought I hustled him, but I didn't. It was a freak, and he's still bitter about it." The differences between Eddie's matches and Negreanu's are significant. Among Eddie's crowd, rules are in place to prevent people from trying to gain an unfair advantage, and the game is more about competition than money. The high stakes are simply a way of keeping everybody playing hard and staying focused. In Negreanu's world, some guys play for their livelihoods, no real mercy gets shown to newcomers, and the rules are loose enough that few people look askance at an opponent greasing his clubheads with Vaseline (to minimize hooks and slices). At his golf-gambling nadir, Negreanu estimates that he fell

To fight back, Negreanu did what all the other high-stakes guys were doing:

He hired a full-time caddie. Now he doesn't play a round without Christian Sanchez, a scratch golfer who had PGA Tour ambitions, on his bag. "I've never gotten to play on the tour, but I play for tour-size money," says Sanchez, 33. Early in their career together, he says, Negreanu squared off against poker pro Patrik Antonius for $150,000 a hole. "Daniel told me we were playing for 150K a hole, like it was nothing. But I had to get my footing under me."

On the course, Sanchez is part teacher, part guardian angel. "Before I began working with Christian, if I started badly I'd fall apart on the fifth hole," Negreanu says. "Christian has shown me how to overcome those situations. Plus he literally lines up shots for me and makes sure I don't get into unfair wagers. In fact, after he reads the green, he physically lines me up. Then I make the putt. He does all the work, and I have all the fun. I've had people ask me if he holds my d---- when I go to the bathroom. But I don't care. Thanks to my caddie, I've won back the $2 [million] or $3 million, plus some gravy. I capitalized on how bad everybody thought I was."

He also found that poker superstar Phil Ivey is one of the best guys to beat at golf. "He's a terrible loser and bitches the whole way. I've seen him walk off the course if he doesn't like how it's going. We played a match once with [handicaps], and he walked off because we were dead even on the ninth hole. He said it wasn't fair." (Golf Digest left multiple messages for Ivey and reached out to a representative, but there was no response from Ivey.)

Veteran gambler Blair Rodman, who has been around the world of golf gambling since the 1980s, has some advice that could have helped Negreanu and others. "If you're going to play golf with gamblers, you need to know that you're not playing golf, you're gambling," he says. "People will try to get an edge; that's how it's done. I don't take anybody's handicap at face value. If you walk in with your eyes closed and make a bad game, you're not going to win."

And if you want to continue playing at this level, you will pay off the loss, even if it feels like you were hustled. Before teeing up with Eddie and his group, known club members get casually vetted to make sure they can afford to lose, and their betting starts slow. "We don't want anybody to get hurt," a regular tells me.

If, say, Eddie has brought you in from outside the club, he'll vouch for your honesty and ability to cover losses. The implication is that, when necessary, Eddie will take responsibility for the new player's debts. Among Negreanu's crowd, participants tend to be known gamblers or friends of known gamblers. Fail to pay up promptly and you'll be ostracized from any future action. You might also find people complaining bitterly about you on websites popular with gamblers, such as twoplustwo.com. If things get really knotty, professional gamblers have been known to call in a third party—usually another gambler—to mediate the dispute.

Layne Flack, 45, another poker pro who has developed a penchant for gambling at golf, lays out a recent on-the-course scenario. It began reasonably enough with a bunch of $100 bets and only a few hundred dollars changing hands after the 18th hole. Next time out, the group upped the wager to an $800-per-hole scramble, plus carryovers, and birdies paying double. "By the ninth hole," Flack says, "they had lost some carryovers and were down like $20,000. They wanted to kick it up to $5,000. I said no, because one birdie would get them $20,000. I let them go to $3,000 per man, I made birdie, and they lost $12,000 to be down $32,000. We went to $5,000 per hole, and by the day's end, we were ahead $64,000. On the next day, it came down to the last hole. ... I let them win a little back. Otherwise, they might not have wanted to pay. I wanted them to realize that they didn't get hustled and that maybe they could have played better. They paid."

Despite his obvious skill as a gambler, Flack insists he's never been much of a golfer. (Take this with as many grains of salt as you see fit.) "I've gotten good only in the last three years," he says. "Back when online poker was booming and everybody had a lot of money, I was a 22-handicap. But I've improved to a 10. So now, when the next online poker boom happens and lots of money is floating around again, I'll be ready."

'IT'S NOT A LIVING, IT'S EXCITEMENT'

Over the past five years, a wholesaler we'll call Richie estimates that he has won $300,000 on some of the best courses in New Jersey. For a while, he says, the cash enhanced his lifestyle. These days, he makes enough in his business that his golf proceeds add up to walking-around money. Nevertheless, he seems to fall into a category of recreational golfers who are just a shade away from the pro gamblers, going at it with the kind of aggression that blurs the line of a friendly game.

Take the time Richie went up against his club's champion for big bucks. That one sounds like the perfect ego boost with the potential for a big score. They play a game that allows them to double the stakes on any hole.

"You either play for double, or he pays off at the previous amount," says Richie, who is in his mid-40s. "Big holes went as high as five grand, and there's no shortage of controversy. If the other guy can't find his ball in the leaves, you're definitely going to double on him. I won $50,000 that day from a guy who wasn't even playing with his own money. His brother-in-law staked him. My feeling is that if you can't put up $5,000 or $6,000 of your own money, you shouldn't even be playing golf."

That said, Richie insists that it's best all around if the stakes among friends don't get too high. "I know guys playing $1,000 nassaus, and the games turn ugly," he says. "At this point in my life, I want to find games where I'm competing for something and finding it enjoyable. Nobody wants to play with the [jerks], and nobody wants to play with the fake-handicap guys. We've thrown guys out of our game for lying about their handicaps. Then I get people telling me that I'm making a living out on the course. I tell them that it's not a living, it's excitement. I make enough to pay my housekeeper. How's that for a living?"

For others operating in the gray area between businessman and gambler, the money reeled in could pay the housekeeper, nanny, chef and gardener. A Texas investor we'll call Matt acknowledges that he'd be disappointed to make less than $100,000 per year from his golf gambling. If he's not playing for fun with his brother on a public course, he's usually looking to raise the stakes on someone. Hearing mention of the Negreanus and Flacks of the world, Matt says, "You don't want to play golf with poker players. They have no money. You want to play golf with businessmen who make a million dollars a year. I like to play against guys with overrated games and plenty of money. Or else maybe an opponent who likes to drink on the course. That will get him a lot of offers for games."

Though Matt tries to keep things fairly friendly with his regular group of players—"Maybe $500 nassaus, five ways"—there are some others with whom he likes to turn up the heat. "I have a couple games that are dead even," says Matt, who says his largest win stands at $90,000 and largest loss is roughly half that. "We start at $500 a hole, birdies are double, and the match is so square that we don't press bets. It's a dogfight and"—he sounds not entirely thrilled here—"nobody's going to make a lot of money in the long term, but, hell, it's a lot of fun." For more serious matches, says Matt, who's in his late 40s, players usually come over from other country clubs or even other states. Such was the case when Eddie and his crew flew in from California. "I played a match with him, played as good as I could play, and just barely beat him," Matt says, adding that the Californians dropped by for several days of golf and gambling. "After the match, Eddie said that he wasn't going to play against me anymore. He said that he'd rather call me partner. I said that was perfect. That day Eddie fell right into the game. We wound up [beating] the other guys, and they're still crying about it."

There are players who get turned on by doling out financial pain. Jason, an entrepreneur who sold his company and now spends his time playing golf for extremely high stakes, has seen it firsthand. He recalls a multi-day match in Northern California. One night, in the hotel dining room, he commented to his primary opponent that the play had been surprisingly close.

"He sat up in his chair," Jason says. "Then he leaned over and said, not in an ugly way, 'Unless I see some of your blood, or you see some of my blood, this is not real exciting for me.' He wanted somebody to lose at least six figures, or else this whole thing would not do much for him. You hear a lot of interesting things and meet a lot of interesting people when you play high-stakes golf."

Though Jason, well into his senior years, does not need the money, he views a six-figure payday as the ultimate trophy. And, to get that money, he works as hard at golf as he did at business. "First of all, I don't ever think about the money," he says. "Instead of thinking about what you'll lose if you miss an eight-foot putt, you should be thinking about the execution of the putt. Once I make a match, the money is immaterial. I'm all about figuring out a way to win. Prior to the match, I work on my weaknesses. Most people who hit the driver good want to bang out balls on the driving range. I devote more time to improving the things I'm not good at. Because there's money at stake, you want to go through the process."

Or else he can go the way of former sucker Daniel Negreanu, who says he has come full circle. "I don't care about gambling at golf now," says Negreanu, who still maintains a golf obsession and continues to work with his full-time caddie. "Every day I hit with a simulator inside my house and practice on the green in my back yard. I don't care about how little we play for, or if we play for money at all. I already have money, so it would be stupid to bet enough that I could get hurt if I lose. You can say that I'm like a regular guy now."

Negreanu hesitates for a beat and seems unsure about that statement. Then he adds, "But, to tell you the truth, I'm always open to gambling—especially if it's a fair situation."

5 TIPS FOR THE NON-BETTOR

You just wanted to play for playing's sake. You didn't need or want the nassau bet or the baggage that comes with it—the trash-talking, the scorecard gymnastics, the handicap whining, the scowls of concentration, or the pressure. But you wound up paired with the club's version of Eddie and his pals. Not wanting to spoil their fun, you played for money—albeit for less than $1,000 a hole—but hated it. As you drove home, you wondered for the thousandth time, Who's the crazy one here, me or Eddie?

The short answer is, neither. The golf gambler is not necessarily the craven degenerate the non-bettor makes him out to be. Conversely, the non-bettor is not the tea-sipping spoilsport the bettors claim.

"People satisfy their golf jones in different ways," says Dr. Gio Valiante, an acclaimed sport psychologist who in 2010 coached seven players to eight PGA Tour victories. Some people—Phil Mickelson is a good example—enjoy the mano-a-mano confrontation. They love golf, but it's more satisfying and more fun when it's personal.

"Then there's the group that would include Jack Nicklaus and Ben Hogan," Valiante says. "They are the 'mastery' individuals. Their opponents are the golf course, improving their technique, honing their strategy. They enjoy competition and beating people, but it's less personalized. They are every bit as invested, but their motivations are different."

Adds Hale Irwin, a three-time U.S. Open champion: "Some people don't feel stimulated if they don't have skin in the game. When I played practice rounds with Lanny Wadkins or Ray Floyd, they always wanted to play for money. I'd go along with it; I wasn't averse to it. But I never felt it took a $50 bet to make me try. I'm always going to play hard anyway."

There seems to be a third set of golfers who go to the golf course for fresh air, exercise, being with friends and observing the beauty of nature. They like the clothes, the gear and the beverage cart. They appear indifferent to improving and, win or lose, smile easily. They often do not carry handicaps. Like their mastery cousins, they aren't particularly enthusiastic about playing for $10.

Population-wise, the last two groups are clearly outnumbered by the betting crowd. If you dislike betting and wonder why the numbers are slanted toward the 80-percent active-betting figure Michael Kaplan references in the accompanying story, you can blame the lure of money itself.

"People have strong emotional, even physiological, reactions when they see money," Valiante says. "We've been conditioned to that outside of golf our whole lives, and that response is not going to be turned off when you go to the golf course. If anything, it's going to be heightened."

So the non-bettor is faced with a decision: Become irritated every time a bet is proposed—which means being irritated most of the time—or somehow learn to accept it. Or maybe even embrace it. Here are some fresh perspectives that will make those nassau propositions bearable.

1. Bettors aren't inherently evil. "Most people who like gambling don't even know why they like it," Valiante says. "They like it for the same reason they like ice cream. It floods the pleasure centers of their brains. They're playing more for personal reward than to inflict pain."

2. Think of it as prep for the member-guest. "I'm a big believer in practicing like you play," says PGA Tour winner Gary Woodland. "When I play for something in practice rounds, I'm not going to let my guard down. It's not a lot of pressure, but it keeps me sharp. It helps me hit the ground running when the tournament starts."

3. It will even out in the long run. For all but the worst vanity-handicappers—players who artificially keep their handicaps low to show off—golf betting is an ebb-and-flow phenomenon. If you play lousy and lose money, your handicap will rise, and eventually you'll acquire an edge and recoup those losses.

4. Make the worst-case scenario acceptable. "Never play for so much that losing hurts you," says Chris Kirk, a three-time winner on tour. "It can sting a little but shouldn't leave a mark. If you're playing for $20 a hole and you're late on your rent payment, that's probably too much."

5. Forget the noise. "The presses, gamesmanship and personalities, they're all clutter," Valiante says. "Forget about them. If you orient yourself to your opponent or the bet, that's when you choke. Focus on the golf course, your next shot and especially the target. Do that, and the results will take care of themselves." —Guy Yocom