Golf's Wisest Man

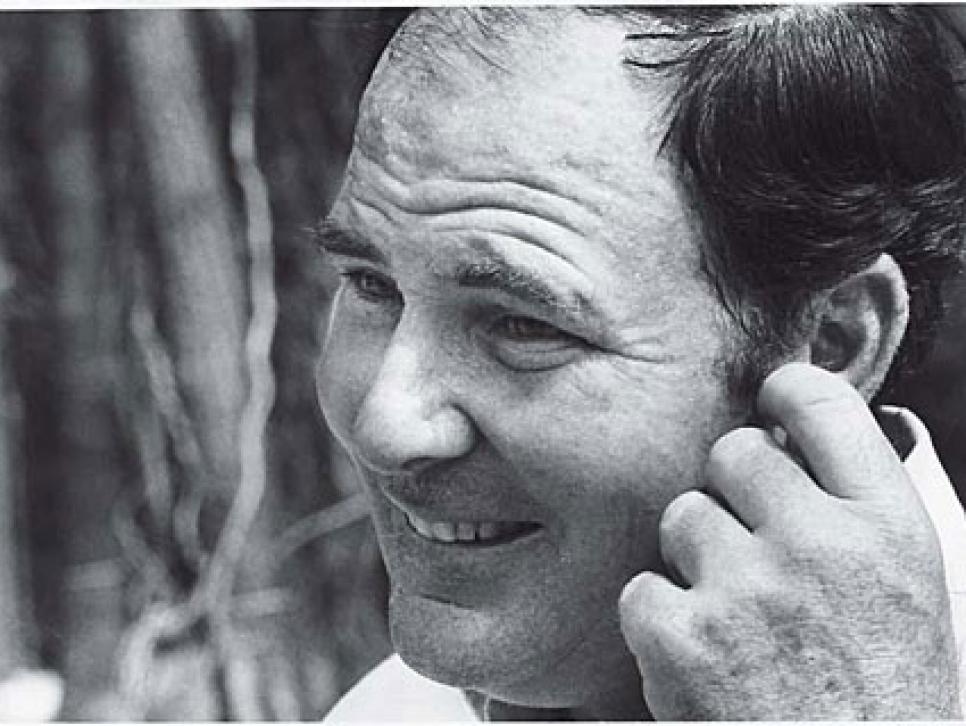

Dye, shown in 1973, remains relevant at age 82 with designs for today and tomorrow.

Although Pete Dye is being inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame for the right reasons, he's easy to get wrong.

Because of the ire that has been heaped his way by tour players angry at the diverse challenges Dye has had the impudence to throw before them at courses such as Sawgrass, PGA West and Whistling Straits, the architect at 82 is commonly seen as a mad scientist. Think of a revenge-driven eccentric who, after completing a menacing mosaic of railroad ties, pot bunkers, island greens and fescue, stands back and cries, Frankenstein-like, "It's alive!"

But get behind the bad haircut, saggy khakis, stained beige windbreaker and sometimes preoccupied manner, and Dye proves not only a clear and reasonable thinker, but a traditionalist. He's firm on the game's main problems—overly high costs, overly fast greens, overly long ball—without denying that his major projects have been complicit in advancing all three. "I have to deal with the game as it's going to be, not what it used to be or what I'd like it to be," he says.

If golf had to choose its wisest man, Dye could present the most complete résumé. His father, known as Pink, built the hilly, nine-hole Urbana Country Club in Ohio, where by age 15 Pete was the greenkeeper as well as a prominent amateur. As a kid he sat on his family's front porch as Walter Hagen and Gene Sarazen spun tales after an exhibition. While stationed at Fort Bragg at the end of World War II, Dye would not only play Pinehurst No. 2 nearly every day, he'd discuss the course's dips and swales with Donald Ross. More than once, Dye was Indian-wrestled to the ground by Babe Didrikson Zaharias, played with and against Jack Nicklaus as an amateur, and regularly with Ben Hogan in the late '60s at Seminole.

‘ have to deal with the game as it's going to be, not what it used to be or what I'd like it to be.'

His longest and greatest association has been with his wife of 58 years and design partner. "Pete and I have never thought about our roles," Alice says. "Whatever had to be done, somebody did. Didn't matter which one."

Dye has funneled all his Zelig-like experience, knowledge, curiosity and energy into the singular ability that makes his courses the best places to measure the true parameters—factoring in constantly advancing equipment—of the modern professional game. More than any prominent architect who is not a former touring pro, Dye possesses a tournament player's knowledge of what emotions particular shots evoke in competition. But more than any former touring pro who is now an architect, Dye possesses the skill and tenacity as a builder to work a piece of land until it tests the best players to their limits—but not beyond.

"The way Pete gets on a property and feels it is pretty impressive," says nascent course designer Tiger Woods. "His courses built for tournaments are hard, but there's a good reason behind everything. We've talked for hours. To get his opinion has been invaluable."

Dye gave some examples during a tour of his latest work in progress, the Pete Dye Course at French Lick Resort, which the PGA is eyeing for its championship. The site, only a mile from a Ross creation where Dye won the 1957 Midwest Amateur, offers majestic vistas from one of the highest elevations in Indiana—a souped-up version of his dad's course at Urbana. But the fairways are among the narrowest Dye has ever built. "These guys keep hitting it straighter," he says, and as he stands in a greenside hollow that presents a shot somewhere between a bump and a flop, he notes, "Pros absolutely hate this shot. Yep, you've got to know what they hate."

He chuckles, recognizing this last remark as potential tombstone material. Even in explaining how he so often gets it right, Pete Dye is easy to get wrong.