What now after Tiger's knee injury?

First Earl Woods knew, or at the very least believed. Then Tiger did as well. The world -- overwhelmed by the ridiculous accumulation of clutch performances that have produced 65 career victories and 14 professional majors has followed. Rocco Mediate spoke for the collective in his reaction to Woods draining the 72nd-hole 12-footer that tied him at the U.S. Open at Torrey Pines. With a perspective that can appreciate genius and a good cosmic joke at the same time, Mediate said, "I knew he'd make it."

But Woods underwent reconstructive surgery on the anterior cruciate ligament of his left knee a week after his playoff victory over Mediate, and now, well, nobody knows. Certainly the odds are that he will recover and become the greatest golfer ever.

But there's a chance he won't, which means even Tiger Woods could be fate's fall guy.

Needing to absorb it all for himself (and ultimately find a way to use it to his advantage), Woods led a contemplative life at his Isleworth home in the days after the surgery.

The numbing routine of post-ACL surgery has always been portrayed as among the darkest days for a professional athlete. There is immobility, pain, the blur of medication and the shockingly fast atrophy of once-chiseled muscle. Woods told friends he was restless, bored and, frankly, down. He distracted himself with movies, video games, Sudoku and reading. Family dogs Taz and Yogi had to get used to their favorite playmate being stuck on the couch, his elevated leg in a straight cast.

After not being able to fulfill his role as host of the AT&T National at Congressional in person, Woods at least was able to give his thumbs a workout by texting suggestions to his staff during the tournament telecasts. He also watched his friend Roger Federer -- another megastar assigned the mantle of inevitability -- lose to Rafael Nadal in an epic Wimbledon final. Sleep was fitful. "It feels like 38-hour days," Woods says.

It has been a year in which he has pondered unknowns more than he has pounded balls. At Torrey Pines, at the end of a week in which his public utterances about his physical condition were evasive and vague, Woods finally chose candor when he admitted, "This week had a lot of doubt to it." In a televised interview during the final round of the AT&T National, Woods said, "As far as golf is concerned, I really don't know," adding, "That's so far away."

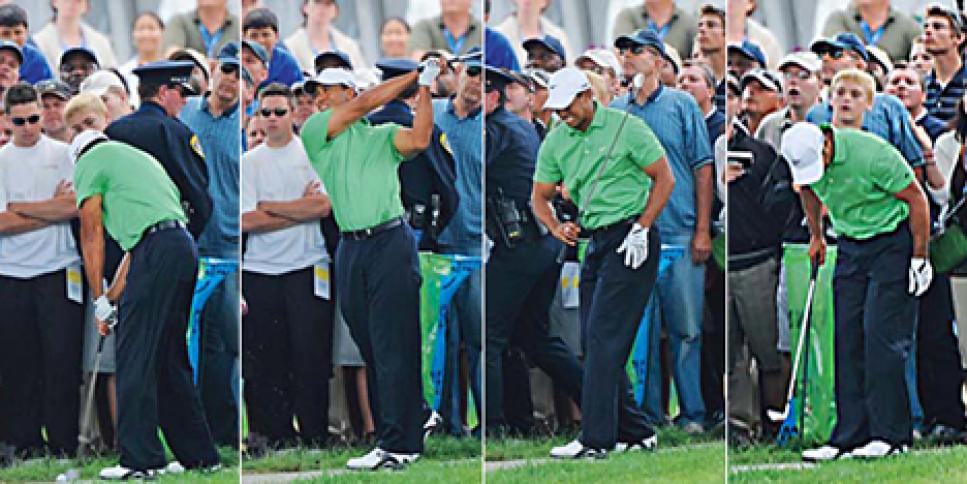

Woods' operatic victory along the La Jolla cliffs, majestic as it was, was also traumatic. After his latest surgery, when Woods reflected on the Open by saying, "I really don't know how I pulled that off" and "That's something I never want to go through again," it was as if the physical ordeal and how close it came to ending in a devastating loss produced an inner shudder. And the truth is, everyone else is still getting their bearings. Watching Woods limp, grimace and even double over in pain as he dealt with an unrelenting U.S. Open course brought home the enormity of what the golf and sports worlds would miss if Tiger Woods lost his gift.

Perhaps sensing that he had created way too much drama, in the aftermath of his greatest victory Woods finally gave a history of his left knee -- albeit the CliffsNotes version.

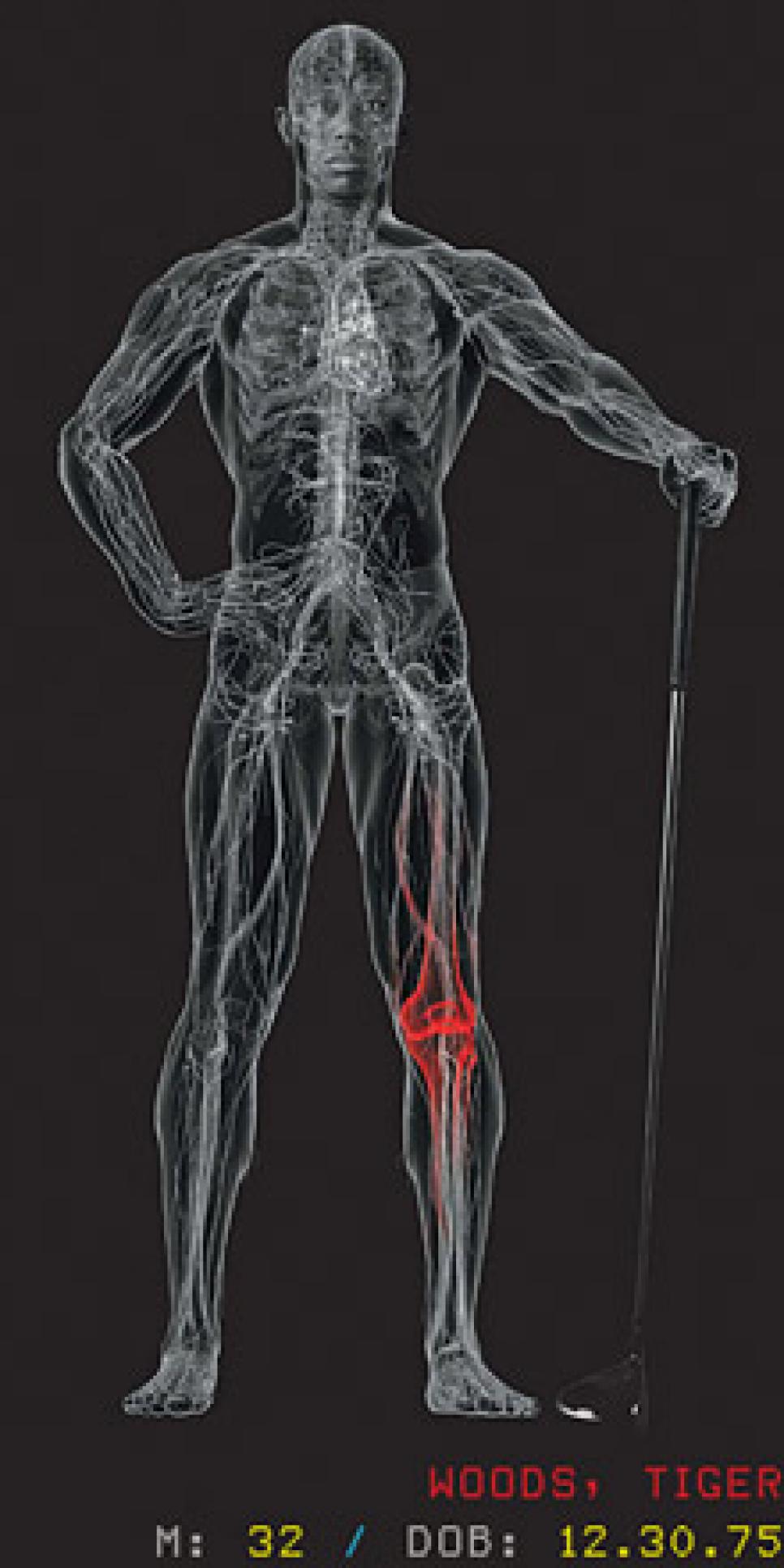

We learned that it has been chronically sore for "10, 12 years." That his ACL was close to shot by the time surgeons removed cysts from the joint in 2002. That when it finally ruptured for good during a run on a golf course after last year's British Open, "everyone was very surprised it had lasted as long as it did."

Woods tried to compensate for the lost stability by stepping up efforts to develop leg muscles strong enough to act as a "checking mechanism" for his "deficient" joint. He took extra time off at the end of last year in the effort, but it was a losing battle. The intense exercise required caused more wear and tear and weakness in the joint, which in turn caused torn cartilage. By March, Woods had to accept that "I couldn't function anymore with what I was doing." With the idea of not missing any majors, he decided to have surgery after the Masters to remove the damaged cartilage. If all went well, he would play in the three remaining majors and then deal with the ACL.

The damaged cartilage was successfully removed, but the normal post-operative reaction left Woods with a loss of strength in the already weakened area that he could ill afford. Trying to build his leg strength in time to play the Memorial as a tuneup for Torrey Pines, Woods applied too much pressure to the unhealthy area, causing two stress fractures in his left tibia.

It forced him to skip the Memorial and caused pain that reduced his practice sessions to a few swings. Doctors recommended he forget Torrey Pines and get on crutches for three weeks, followed by three more weeks of rest. Instead, Woods determined that his knee was about as hurt as it could get in the short term. And, because he was absolutely determined to play the Open at a course where he had already won six times as a professional, he decided he could handle the pain.

Quite a saga, but here's the upshot: The 12 years of soreness and surgeries (see accompanying chronology below) didn't stop Woods from compiling a record and rate of victory that surpasses all before him. Without a functional ACL from August of last year to June of this year, Woods played in 13 events, winning 10, finishing second twice and fifth once. And with the shooting pain from stress fractures that worsened with every round, Woods walked 91 holes and won the Open.

In that context, the brutal ACL rehab seems well within Woods' comfort zone. As orthopedic surgeries go, the procedure has become so common as to be considered relatively low-risk. The specialist who has performed three surgeries on Woods' knee, Dr. Thomas Rosenberg, says that "it is highly unlikely that Mr. Woods will have any long-term effects as it relates to his career."

Woods will need patience and prudence, making sure that the grafted tendon from his right thigh that now serves as his left ACL is allowed to make a full and healthy connection. After that, he'll need discipline and determination to rebuild his muscles and regain full motion. With so much riding on the outcome, it would be a huge surprise if Woods indulged his risk-taking bent and in any way defied doctors. "I can assure everyone that I'll be as dedicated to rehabilitating my knee as I am in all other aspects of my career," he says.

There is no rush to come back. More than ever, Woods' career is all about the majors. Anything that gets him whole and ready by next year's Masters in April will be fine.

Though ACL injuries can be problematic for athletes who are required to make high-speed cuts and deal with contact, Woods is a golfer. For all the extreme forces that he supposedly puts on his left knee when swinging the club 125 miles per hour, orthopedic doctors say that ACL tears as a direct result of the golf swing are extremely rare. Both Brad Faxon and Ernie Els, to name two professionals who recently underwent ACL reconstruction, were injured in activities outside of golf.

Photo: J.D. Cuban

But veteran long-drive champion Art Sellinger says that the lead knee of the hardest swinging golfers frequently give out, particularly because they commonly hyperextend the joint through impact in the search for maximum yardage -- a move Woods has been trying to lose in his swing since his 2002 operation. "Mostly it's meniscus and cartilage tears," says Sellinger, 43, who has had two surgeries on his left knee. "But I've never seen or heard of a long driver tearing up his ACL making a swing."

Still, many reasonably wonder if a post-surgery Woods will be physically compromised, causing him to lose some of the dominating length and power that is his biggest physical advantage over the competition. But his swing coach, Hank Haney, though sad that the knee problem became untenable at precisely the time Woods had incorporated swing improvements to the point that he was playing his greatest golf, is optimistic and eager for the future.

"I don't see how having a repaired and healthy leg again won't make Tiger better," says Haney. "All this last year with the ACL tear, his strength was down, his speed was down, he couldn't practice like he wanted to, couldn't exercise like he wanted to, was in pain, on medication and frustrated. Once he gets a strong stable leg again, it's just logical that he's going to get better. I don't care if he won 10 out of 13, that's not the measure of how good Tiger can be. Anybody who doesn't think he's going to be better than ever doesn't know Tiger."

Contrary to those who think that Woods will have to swing less forcefully and otherwise change his action to protect his knee, Haney says that the surgery will allow Woods to more consistently execute the same swing he has been trying to master.

"He's been working for a while on making his leg action better, basically getting onto his left side better," says Haney. "But again, with the injury, there was a tendency for his hips to back up going through the ball, and he'd raise out of the shot. That's why he had trouble stopping his knee from snapping straight through impact -- he didn't have enough in the joint to hold the flex. With a good leg to hit against, he'll be able to really move his weight forward toward the target. That's more power and more accuracy."

Of course, even if Woods ends up better, he might never produce a better performance than he gave at Torrey Pines. For all the spectacular shots that Woods needed to make because of a larger-than-normal rate of bad ones, two will stand out, and they occurred back to back on the par-5 72nd hole.

The first was his third shot, 101 yards from a front pin with his ball in primary rough. Woods, needing a birdie, had put the ball in this difficult spot by fanning his second from a fairway bunker. He had gotten so angry at such a bad error in such a crucial moment that he whacked his bag with the club hard enough to cause three balls to fall out.

Caddie Steve Williams knew that though Woods would normally hit a 56-degree wedge, the height and spin needed to land and stop the ball near the hole could only come from a perfectly struck 60-degree wedge. Williams later said pulling that club was perhaps the best call of his long career. Woods did his part, his extra-hard swing juicing the ball enough to spin it back toward the hole.

Photo: J.D. Cuban

The stroke that followed will go down as the greatest final-hole putt in the history of major-championship golf. There are plenty of candidates: grinding mid-rangers by Bobby Jones at Winged Foot, Payne Stewart at Pinehurst, Gary Player, Mark O'Meara and Phil Mickelson at Augusta, Seve Ballesteros at St. Andrews; no-brainer bombs by Jerry Barber at Olympia Fields, Hale Irwin at Medinah and Costantino Rocca at St. Andrews. But none of them surpassed Woods for the blend of setting, situation and reaction. And only Jones, arguably, had as much disappointment to face by missing. Never in golf has such a dramatically set stage had such a fulfilling resolution. As a final validation of a true stroke at the moment of truth, a close-up, slow-motion replay revealed that the alignment line on Woods' ball never wiggled until it fell into the hole.

It's a memory Woods will undoubtedly call on for inspiration during the difficult days of his sabbatical, which barring another enforced absence will likely come to be viewed as the break between the two halves of his career. Just as his body was wounded, so to some extent was his psyche.

Awareness of vulnerability -- on or off the course -- can weaken the mind-set of a champion. Now that Woods realizes how fragile even the most gifted life can be, will the self-perpetuating certainty that guides him when the pressure is highest -- that because he has done it before, he will do it again -- seem as uncomplicatedly true?

Interesting life questions, and in Woods' case, it's a blessing that he will have several months to think. Last year, after the downer of the British Open, it was a prolonged inner examination over several weeks that brought him back a better golfer. Now he will have even more time to gather himself.

"The way Tiger can work things out by himself -- whether it's his swing or anything, really -- that's one of his greatest attributes," says Haney. "Once he understands what he wants, he has this ability to visualize it, mentally rehearse it and incorporate it into his game or in his life. The day before surgery, he asked me for a list of things we're going to work on. He said he wants to think about them. Believe me, I know him. He's going to come back better than where he left off."

TIGER'S KNEE CHRONOLOGY

Tiger Woods says he first hurt his left knee skateboarding as a child. Since then he has had four surgeries on the knee and says, "Basically, my left knee's been sore for 10, 12 years." A timeline:

DECEMBER 1994

As a freshman at Stanford, undergoes surgery to remove two benign tumors and scar tissue.

DECEMBER 2002

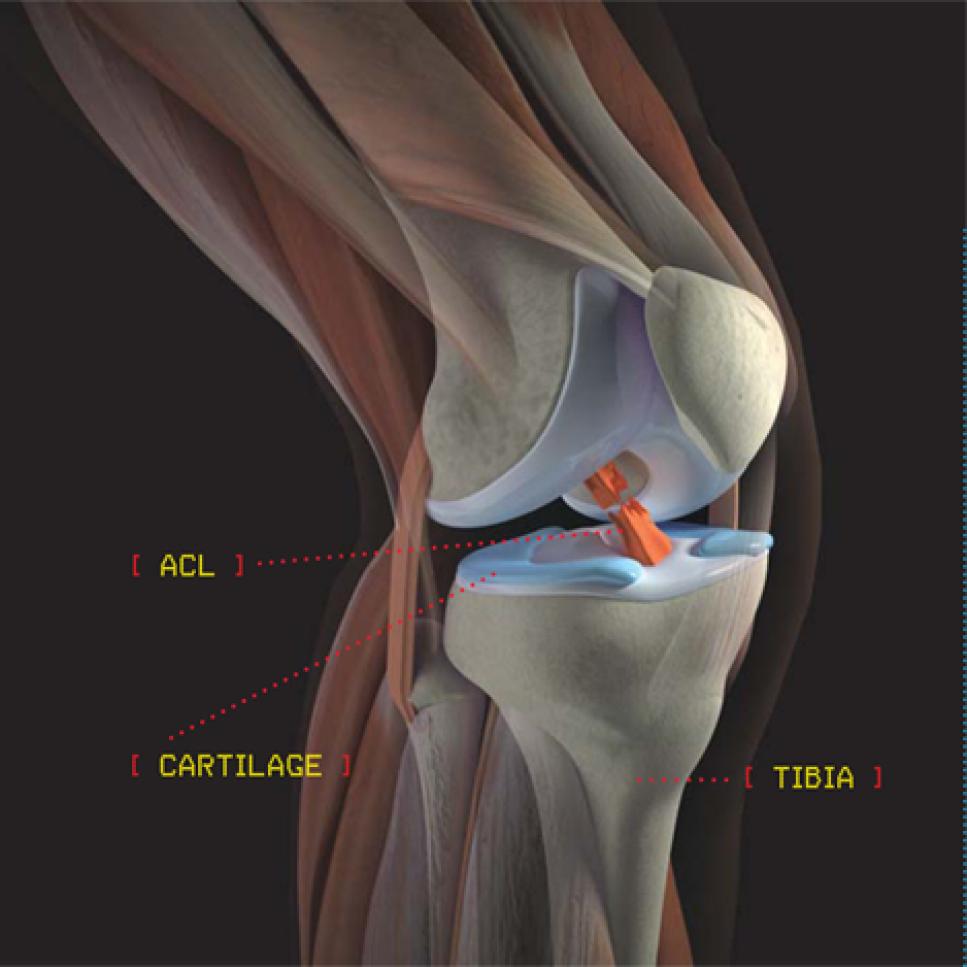

Has surgery to remove fluid inside and outside the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and to remove benign cysts. It is from this surgery that Woods learns that the ACL, which connects the lower part of the thigh bone to the upper part of the main bone of the lower leg, is damaged. "There wasn't a whole lot left," he says, adding that he was told by doctors, "'You need to train and develop your hamstring and glute and calf as much as you possibly can to hold it.' Everyone was very surprised it lasted as long as it did before I ruptured it." Woods later wins the 2003 Buick Invitational in his first tournament after the surgery, but after winning seven of 11 major championships ending with the 2002 U.S. Open, he goes winless in the majors in 2003 and 2004.

SUMMER 2007

Ruptures the ACL. Woods says the final tear occurred when he took a misstep while running on a golf course after the British Open but is able to continue playing. (There is no lasting pain from the ACL beyond the initial injury, and some athletes in golf and other sports have been able to continue to compete without surgery.) Wins five of the final six tournaments he plays that year, including the PGA Championship.

APRIL 2008

Two days after finishing second in the Masters has arthroscopic surgery to repair cartilage damage but does not have the ACL repaired, hoping to avoid the longer rehabilitation and give himself a chance to play the U.S. Open, British Open and PGA Championship.

A layer of cartilage within the knee joint covers the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone) and patella (kneecap), allowing the bones to glide against each other without damaging the bone. "The natural rotation of the golf swing without the ACL made it a little bit unstable," Woods says, "and it caused some cartilage damage because of that... When they went in there, they discovered some more cartilage damage that they'd have to fix in conjunction with the ACL reconstruction, and it was going to be kind of a double dip there. And I waited to do that."

MAY 2008

Is advised just weeks before the U.S. Open that because of two stress fractures of the left tibia, he should expect to be on crutches for three weeks and be sidelined for an additional three weeks. The double stress fracture is attributed to Woods' "intense rehabilitation and preparations" for the U.S. Open.

JUNE 2008

Wins the U.S. Open, going 91 holes, then has surgery eight days later to repair the ACL (using a tendon from his right thigh); additional cartilage damage also is repaired. Doctors say the stress fractures will heal with time off. As for the ACL, "Everyone heals at a different rate," Woods says. "Some people are back to playing sports in six months, some are nine, some are 12. So to be honest with you, no one really knows until we start the rehab process and see how this thing heals."