The Loop

A century after his birth, Ben Hogan still fascinates

By Bill Fields

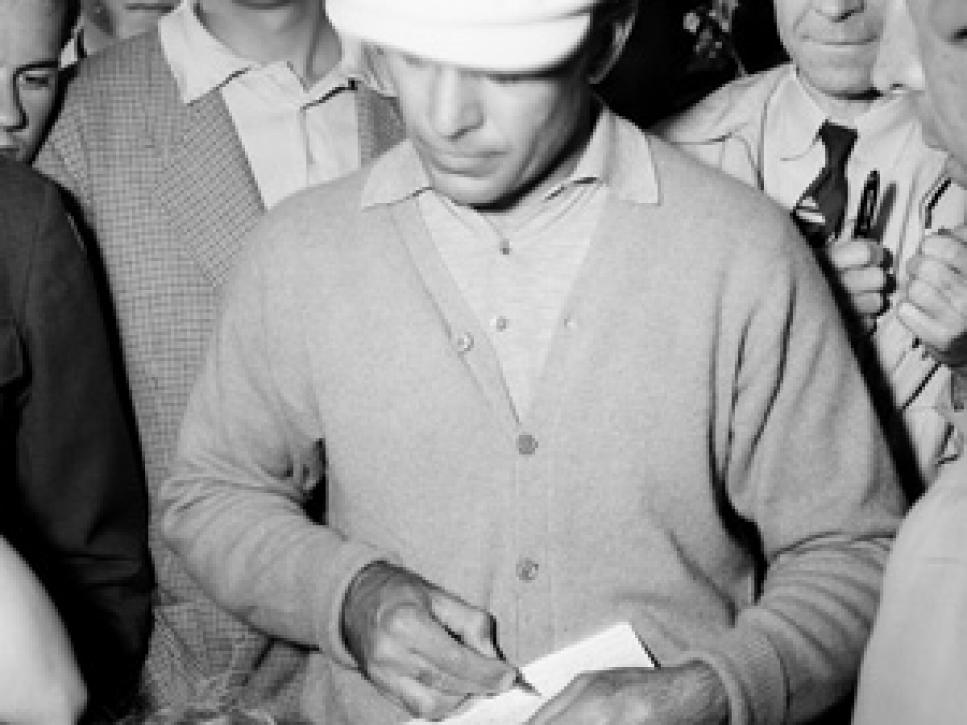

A century since his birth, on Aug. 13, 1912 in Stephenville, Texas, Ben Hogan still fascinates.

He was a man -- and most especially a golfer -- different from most. Hogan came up hard and played hard, and he saved his soft side for a few.

To think of Hogan is to think of a quest to get better and the effort, the physical and mental sweat, that it took. Writers (James Dodson, Curt Sampson, even the LPGA player Kris Tschetter in a memoir of the "Mr. Hogan" she knew) have effectively probed behind the curtain to reveal the man in recent years.

We know more now than did those who marveled at his technique and perseverance -- his singularity -- in the middle of the 20th century, but some things still cause pause. How could Hogan have won six of his nine majors after the 1949 car-bus accident that nearly killed him, devastating his body? It doesn't seem possible, yet he did so by applying himself to a pursuit of perfection that wasn't a slogan, but a way of life.

There was no mystery nor secret to the toil on the journey to the trophies. As Lanny Wadkins says on "American Triumvirate," a solid Golf Channel documentary about Hogan, Byron Nelson and Sam Snead that premieres today at 9 p.m. EDT, "I never saw him take a shot off." That's simple praise for a complicated man, advice as valuable in this century as the last.

I was lucky enough to spend a bit of time around Nelson and Snead in their later years, more with the latter, as they happily got more recognition for their groundbreaking achievements. The two men, as different as Texas and Virginia, were pleasures in their distinctive ways to be around, proud someone wanted to poke around their accomplishments and acknowledge the way it had been.

As for Hogan, I regret I never got the chance to talk with him, shake his hand, sense the powerful presence, get fixed in his stare. The closest I got to him was in Pinehurst, 1974, at the opening of the World Golf Hall of Fame, when I was kid standing amid pine trees observing a man in suit who had dressed up competitive golf as few ever have.

On the centennial of Hogan's birth, I have to be content to know people who knew him.

A hundred years from now, no one will be able to have even that opportunity. But golfers will still care about the golfer who cared so much.