If you want to put golf back on the front pages again and you don't have a Bobby Jones or a Francis Ouimet handy, here's what you do: You send an aging Jack Nicklaus out in the last round of the Masters and let him kill more foreigners than a general named Eisenhower.

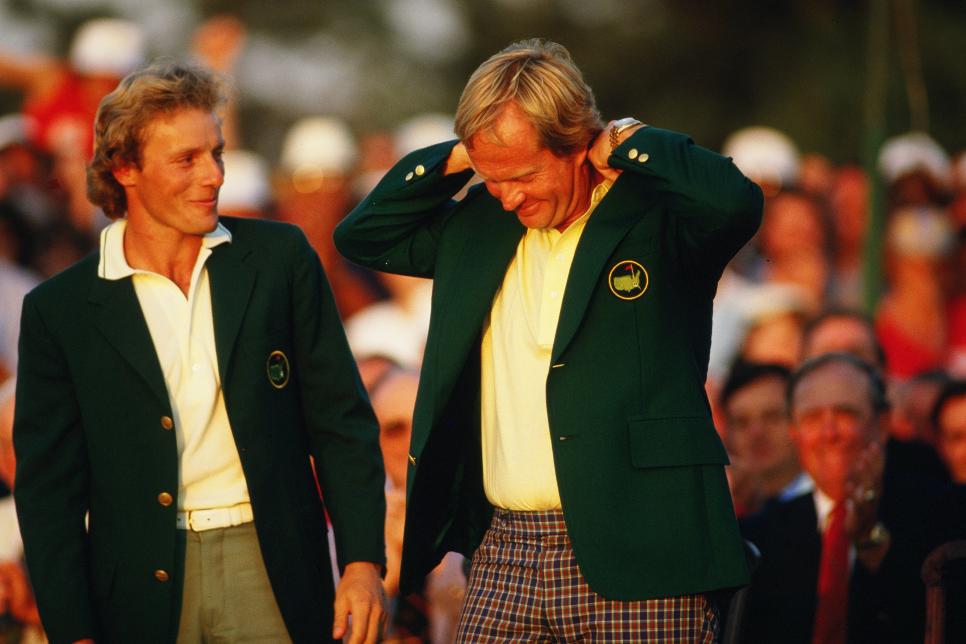

On that final afternoon of the Masters Tournament, Nicklaus' deeds were so unexpectedly heroic, dramatic and historic, the taking of his sixth green jacket would certainly rank as the biggest golf story since Jones' Grand Slam of 1930. That Sunday night, writers from all corners of the globe were last seen sitting limply at their machines, muttering, "It's too big for me."

What indeed could be said? That it was one for the ages? That Jack Nicklaus saved golf from the nobodies who populate the PGA Tour these days? That surely this was Jack's finest hour, this 20th major? As much was said back in 1980 when he surprisingly won the U.S. Open and PGA. But here he comes again, six years later, now a creaking 46, hopelessly trailing a group of younger stars, most of them glamorous foreigners like Seve Ballesteros, Greg Norman, Bernhard Langer, Tommy Nakajima, Nick Price and Sandy Lyle and what he does is suddenly catch fire over the last 10 holes of the tournament, shoot a seven-under 65 (with two bogeys), knock all of the invaders into a killer funk and win a sixth Masters by filling the Augusta National's pine-shadowed corridors with roars unlike any before them.

And he does it at a time when it looked like you needed a visa to get on the leader board. He had to beat a league of nations.

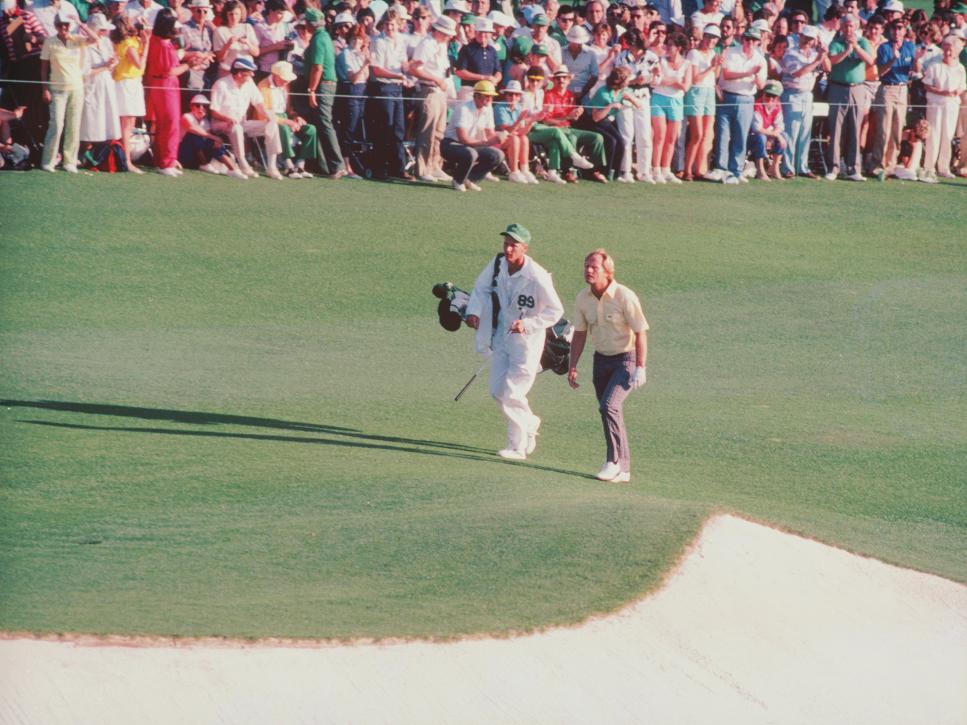

This history book, please. Now that it's over and Jack has hugged his son, the caddie, and survived the cordon of policemen who hadn't surrounded a golfer in such numbers since Jones completed the Slam at Merion 56 years ago, or since Ouimet upset Vardon and Ray 73 years ago, what does it mean?

When he won his fourth U.S. Open at Baltusrol in 1980, it tied him with Ben Hogan, Bobby Jones and Willie Anderson. When he won his fifth PGA at Oak Hill in 1980, it tied him with Walter Hagen. Now look, Nicklaus' sixth Masters victory gives him a tie with none other than Harry Vardon in an odd category. Vardon had been the only professional to win a specific major six times, having taken his half-dozenth British Open at Prestwick back in 1914.

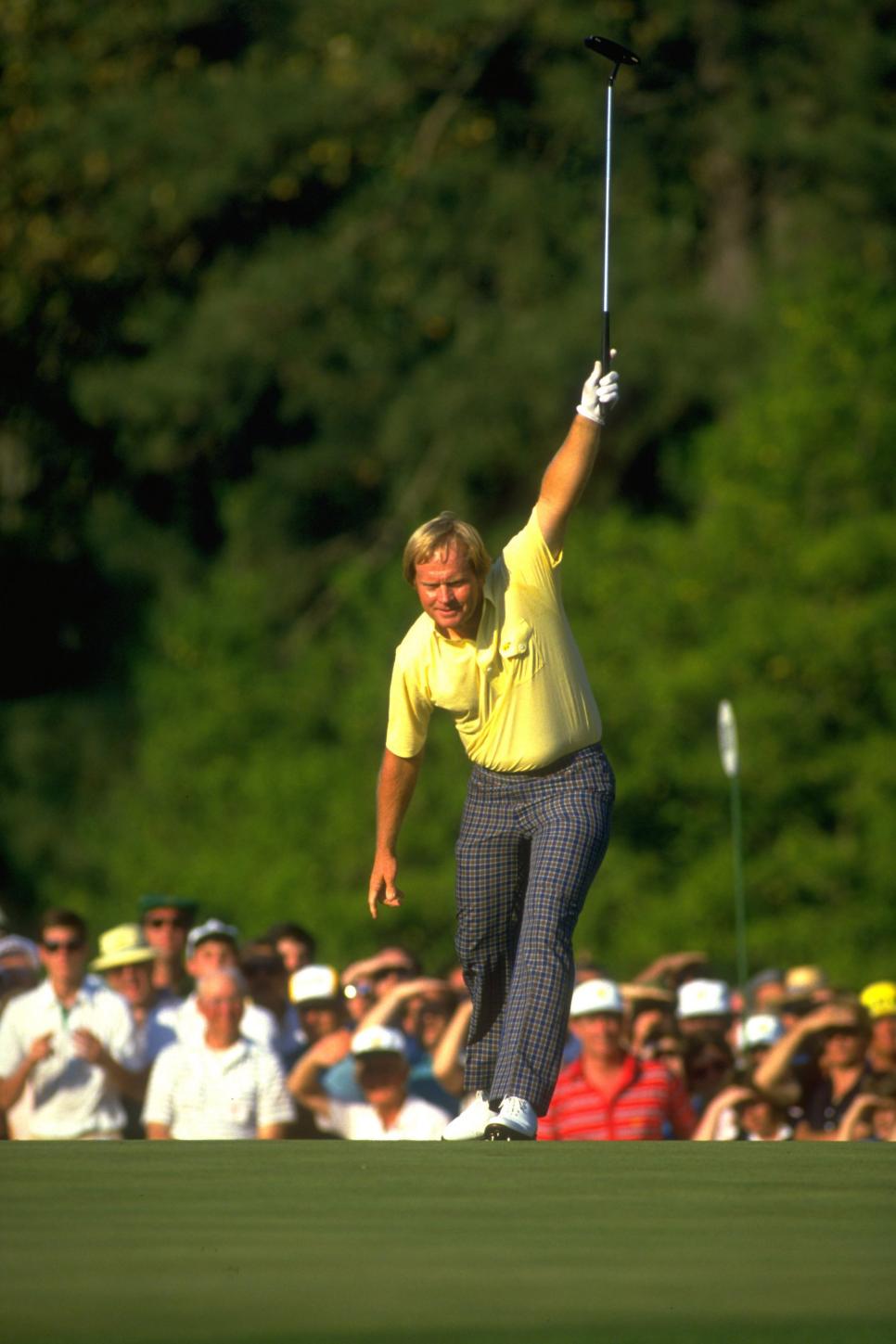

In the case of Nicklaus, it wasn't so much that he did it but how he did it. With 10 holes left in the final round, Jack was six shots off the pace being set by Seve Ballesteros, who simply looked as if he owned the tournament, and had been looking like the owner all week long. But let it be recorded that Jack played those last 10 holes in 33 strokes--with a birdie at the ninth, a birdie at the 10th, a birdie at the 11th, a bogey at the 12th, a birdie at the 13th, a par at the 14th, an eagle at the 15th, a birdie at the 16th, a birdie at the 17th and a par at the 18th. Poor Jack. The guy almost didn't know how to make a par.

To be serious, it was a miraculous stretch of holes that tore the foreigners apart. None among them had a reason to take Nicklaus seriously until Jack hit the most gorgeous 4-iron you ever saw to the water-guarded 15th and then rammed home a 12-foot putt for an eagle 3. That got their attention, and then when Jack put every pore of knowledge into a 5-iron and damned near aced the par-3 16th, it frankly scored a knockout over Ballesteros.

There stood Seve, back in the 15th fairway with a one-shot lead on the field. Here was a man who had already made two eagles in the round, one at the eighth with a 50-yard pitch and another at the 13th with a two-yard putt. Until this moment, Seve had looked indestructible. But the repetitious punches of Nicklaus finally got to the Spaniard, and he did the only thing he could have done to lose the tournament he wanted so badly to win. He jerked the worst-looking 4-iron shot imaginable into the pond with a one-handed finish and took a bogey that bruised his confidence beyond repair. Make no mistake: Jack knocked the club out of his hand.

Perhaps the next most amazing shot Nicklaus hit came then at the 17th, after his pulled drive left him on hardpan, 125 yards from the green. A shot like that is supposed to spin, but Jack just fluttered it up, hop, hop, and he had a 10-foot birdie putt that destiny would allow him to rap into the throat of the cup. Finally, he played to a masterful par at the closing hole for his winning total of 279.

Nicklaus has rarely won his stockpile of majors watching television--until this one. In the Jones cottage near the Augusta National clubhouse, Jack watched the failures of Tom Kite and Greg Norman.

Of these, Norman's was the most necessary, and perhaps the most deserving, given the fact that the way Greg struck the ball on Sunday, his 70 could well have been an 80. He bounced off of everything but a nearby shopping center, and kept getting saved by the crowds, whose numbers prevented his ball from finding even worse places to come to rest, or, in fact, be lost. It was Nicklaus' presence on the scoreboard that ultimately did in the Australian at the 18th hole when Greg needed a par to tie, just as it was Jack's presence on the course that had done in Seve and others. What do you do if you're Greg Norman in the 18th fairway of the Masters on Sunday and you're trying to get Jack Nicklaus into a playoff? You hit a half-shank, push-fade, semi-slice 4-iron that guarantees the proper result for the history books. When you stop to think about it, Norman probably didn't want to play the 10th hole again in sudden-death; he already had double-bogeyed it twice that week, once four-putting. Oh well, Greg Norman always has looked like the guy you send out to kill James Bond, not Jack Nicklaus.

David Cannon/Getty Images

When it was all over, including the shouting, Nicklaus sat in front of the 300 writers and explained the meaning of winning the Masters in "the December of my career." He said he never heard the crowds roar so loudly. "There were only three other times that compared," he said. "The 1972 British Open at Muirfield when I lost to Trevino, the 1978 British Open when I won at St. Andrews and the 1980 U.S. Open I won at Baltusrol. It brought tears to my eyes.

"I'm not as good as I was 10 or 15 years ago," he went on to say. "I don't play as much competitive golf as I used to, but there are still some weeks when I'm as good as I ever was."

There was nothing to recommend Nicklaus going into the week. He hadn't won a major in five years. He hadn't won a minor in almost two years. He had missed three cuts this year. His best finish of 1986 was a tie for 39th in Hawaii. It was even whispered on the clubhouse veranda that he was having business difficulties. But there was one thing nobody at Augusta noticed, except for Jack and maybe his caddie. Next to Ballesteros, Jack had played the best golf of the week tee to green. All he had to do was make some putts.

As usual, Jack gave credit to a short-game lesson he got from his son. This time it was Jackie who passed along a tip from Chi Chi Rodriguez to "take the hands out of the swing, firm up the left side and move more aggressively through the ball." (You may recall back in 1980, he was trying to put the hands into the swing, soften up the left side and move more passively through the ball.)

But the credit really belonged to that outrageous putter he used to hole all those putts. Jack has putted with an old George Low flange in almost every major he won. The last time he deviated and won was in the 1967 U.S. Open at Baltusrol, with a putter named "White Fang." Now he's using a putter he helped design at MacGregor, something on the order of an oversized Ping. What do we call this one? Fat Fang? Or how about, the Pregnant Ping? And what, God help us, will it do to the putting strokes across the country?

As for the rest of the year, Jack said he'll be playing a limited schedule: the Memorial, the U.S. Open, Canadian Open, British Open, PGA, the International and the World Series. "I'm not going to retire, guys," he said. "I'm not smart enough to do that."

Nicklaus' incredible feat in this Masters underscored the fact that there's something about the second weekend in April that's quite impossible to change. The golfing year starts in Augusta, Ga. You feel it every year. They can play the Tournament of Champions in January, and they can claim all kinds of privileges for the Tournament Players Championship in Ponte Vedra, Fla., in March, but it's the second weekend in April when true excitement and elegance kick in, when the golfing establishment assaults the veranda, when the world media congregates and when the players themselves know they're in the big time. At Augusta, there are no junk-food franchises sponsoring the marshals, no take-out restaurants catering to the press, and the only logo to be seen on everything from a visor to a paper clip is that of the Augusta National.

The Masters is a sell-out annually, and even the scalpers mind their manners. Outside the club property, across the street from Magnolia Drive, a man was selling Masters hats this year. Someone had been told to go see him for a ticket. "I'm not selling tickets," the proprietor of the hat stand said. "I'm selling hats."

Strangely, the hats for sale had what looked like Masters tickets pinned to them.

"How much is a hat?" said an interested buyer to the man in the hat stand.

"Eight hundred and fifty dollars."

In the Augusta National golf shop, the articles with Masters logos virtually fly out of the room--the jackets, caps, towels, ashtrays, shirts, coasters, etc.

Very early in the week, a souvenir hunter wandered over to the jewelry and glassware counter, interested in pendants, money clips, paperweights.

"I'd like to have one of those Masters paperweights," he said to the lady behind the counter.

"Sir, I'm sorry," the lady said. "A Japanese gentleman was just here and bought the only 60 we ordered."

As most Masters junkies know, the Augusta National does not have a pro-am or a clinic, but it does have the Par-3 Tournament on Wednesday, a chance for everyone in the select field to gather some crystal they may not be able to collect during the tournament proper. The Par-3 is more like a picnic than a competition, but the crowds are enormous. No winner of the Par-3 has ever gone ahead to capture the Masters, and Gary Koch was no exception this time.

For most, the high point of this year's Par-3 was noticing a group of spectators in Bob Tway's gallery wearing shirts that said: "Tway's Twoops." The sighting of these people together with the fact that PGA Tour Commissioner Deane Beman was the only establishment person missing from the Augusta veranda said something, in a curious way, about where the sport has come in America since the days of "Arnie's Army," or even "Lee's Fleas." How could the commissioner not have been present at what is undeniably golf's foremost social occasion? And is "Tway's Twoops" the tenor of the humor we can expect from the future of the PGA Tour? What Beman missed, of course, was one of golf's most epic occasions.

David Cannon/Getty Images

The first round of the Masters on Thursday looked pretty much like every other tour event of the past two or three years. It was rather bland from the standpoint of thrills, and when the day was done, Ken (not Hubert) Green was tied with Bill Kratzert for the lead. They had shot 68s. Green had done it by holing an abominable number of long putts. Somebody said the only green he hit was Shelley, his sister, who caddies for him.

While Shelley is a cute thing, her presence nevertheless brought to mind that the Masters maybe shouldn't have given in to the touring pros four years ago and allowed them to bring their own caddies to the tournament--for their own good. Ken and Shelley Green's lack of knowledge caught up with Ken and he dropped out of sight. In the old days, such caddies as Ironman Willie and Stovepipe contributed an awful lot to the reading of breaks and club selections because they knew the subtle contours of the course the way they knew the eyes on a pair of dice in the caddie pen. But, then, Jackie Nicklaus didn't do too badly, did he?

Weather-wise, Friday was just like Thursday, an old-fashioned, breezy, slightly cool day, the kind of day that reminded grizzled veterans of the '50s and early '60s. It was a day that was much to the accomplished player's liking, one that rewarded good shots and placed a premium on knowledge. And it more or less belonged to Ballesteros, whose four-under 68 was highlighted by an eagle-3 at the par-5 15th, the same hole that would do him in later. His eagle was the result of two stylish swings and a 20-foot putt. In his eyes, Seve had the look of eagles all the way around, having already said he was "ready to win." Of everyone involved, Ballesteros looked the most determined, the most dedicated, the player with the most motivation, having been banished from the American circuit for 1986 by the stubborn enforcement of a silly rule, or so growing numbers of fans, journalists and competitors are beginning to believe.

On this subject, Seve said in a press conference, "Deane Beman is a little man trying to be a big man."

After his Friday round, Ballesteros found himself in an exchange with the Atlanta Journal's gifted columnist, Furman Bisher, a conversation worth repeating.

Furman said, "Seve, you played like you were on a crusade today. Are you trying to prove something to the PGA Tour?"

Seve responded, "Did Deane Beman pay you to ask that question?"

Furman said, "No, it's a legitimate question. Are you on a crusade?"

"You talk too sophisticated for me," said Seve. "I don't understand."

"You ought to know what a crusade is," Furman said. "They started in Spain."

Seve didn't have a kicker line because like most everybody else in the press building, he'd never learned that the Crusades had actually started in Rome.

Saturday was the day that the Augusta National course played easier than it ever had, or perhaps ever would again. The greens had been watered to begin with--reason unknown--and then the place got caught in a calm. Soft greens and no wind. The course was bound to take its bruises, and did. The average score of the field, those who had survived the 36-hole cut, was 70.98. Shots flew into greens and went splat instead of bounding into the dogwood. Tom Watson said it was the "most defenseless" he had ever seen the course.

All sorts of competitors took advantage of the conditions to play themselves into contention, primarily because Ballesteros had one of those days when he played flawlessly from tee to green, at least for 16 holes, but never made a putt. He seemed always to be in just the wrong place on the undulating greens to get a "good read."

Nick Price was the player who committed the most brutal rape of the premises. There were several things astounding about Price's record 63. One, he bogeyed the first hole. Two, he had a "margarita" on the 18th, a birdie putt that rimmed the entire cup but stayed out. And three, he never hit a single par-5 hole in two and yet birdied all four of them. This was the same Nick Price who had begun the tournament with a woeful 79 on Thursday, mostly because of six three-putt greens. It was the same Nick Price who comes from Zimbabwe, or Rhodesia if you insist, but holds a British passport and is applying for U.S. citizenship. A nice, friendly guy and a stylish swinger. The guy who blew the British Open to Watson at Troon in 1982, remember? A guy who was a lurking contender in the PGA last summer at Cherry Hills. He had been in the threesome with Hubert Green and Lee Trevino but went unnoticed. "Hubert didn't play as well as I did that day, but he beat me by four shots," said Nick, who had learned something. "It comes down to character on the last five or six holes in a major." Every foreigner learned this at the 50th Masters, thanks to Nicklaus.

The main thing Nick Price could say about his remarkable 63, and the putt on the 18th green that would have made it a 62, was: "I think Bobby Jones held up his hand from somewhere and said, 'That's enough, boy.' "

What the pushover conditions on Saturday did was create the possibility of a swarm-off finish. There were 21 players only five strokes apart when Sunday's final round began. Norman was leading at six-under 210 after rounds of 70, 72, 68, and both Ballesteros and Langer said they "liked" their positions at 211. With five foreigners up there among the top eight contenders, it looked like America might be better off trying to take up cricket.

Augusta National

The situation was ripe, however, for someone to go out early, shoot a low number, and maybe steal the thing. That Jack Nicklaus, a 46-year-old golf course designer, would be the one to do it was the last thing in anyone's mind.

So now quite astonishingly Nicklaus has left our mouths agape by winning major championships 27 years apart, from the U.S. Amateur at the Broadmoor in 1959 till old Fat Fang brought him up the 18th at Augusta. But listen, just because he has tied Harry Vardon for six victories in a major, it doesn't mean there's nothing left for him to do. Historians tell us that a gentleman named John Ball once captured eight British Amateur titles. Let's try a new lead, then.

Chasing John Ball, comma, . . .

EDITORS' NOTE: This story first appeared in the June 1986 issue of Golf Digest