Coming Back

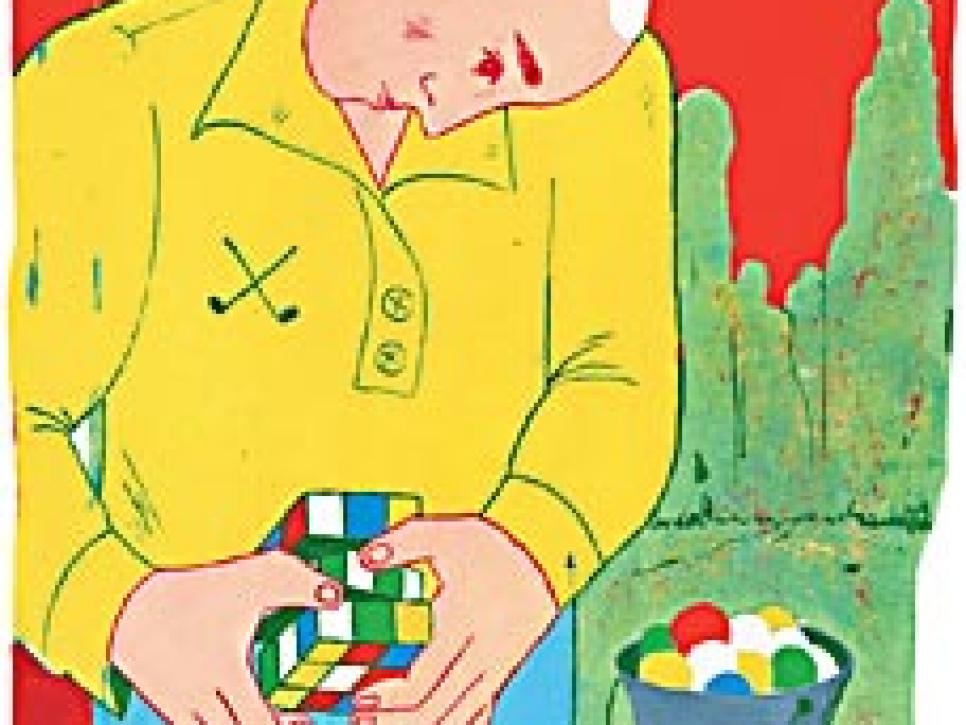

My father stares down at his hands.

Slowly, as if solving a Rubik's Cube, they find the overlapping grip he has been using for 50 years. He waggles the club hesitantly. When he swings, his upper body appears cemented on its axis, and his hands don't get much above waist high. The descending blow is more of a stab than a swing, and the ball ticks harmlessly off the toe of his club and dribbles directly right, crossing in front of the only other player who is on the practice tee this late on a September evening. Our fellow member is polite enough not to look back over his shoulder at us.

"See?" my father says. "They're all like that."

And then, as if to demonstrate, he slowly rakes another ball into his stance, stares down at his grip and does the same thing again. This time, as the ball rolls away, my father lets the clubhead fall with a heavy thud against the unmarred turf in front of him. This is his version of a temper tantrum.

A lacunar infarction is what the doctor called the mild stroke my father suffered four months earlier, so named for the crescent-shape void of synapses deep in the brain that appears like a scar on the CAT scan. There were several of them on my father's scan, evidence that his increasing forgetfulness in recent years hadn't been the result of the natural aging process, but was instead caused by a series of tiny strokes that eventually led to the more significant one on Mother's Day. That morning, his face fell of its own weight, his tongue became a useless, oversized piece of chewing gum in his mouth, and his eyes showed something I had never seen in the 40 years I had spent with him: fear.

"Is your back OK?" I ask him now. My father has had a creaky back since I was a kid, the muscles at the base of his spine periodically clenching in a spasm so severe that my mother had to dress him for work. Staying home in bed was the recommended treatment, but self-made men all share a common aversion to sick days. "I just need to get up and move around," my father would say, hunched like a question mark and shuffling toward the front door in a three-piece suit.

"My back's fine," he answers. "Why?"

"You're not turning," I tell him.

"Hmm?"

"You're not making a turn. You're just sort of lifting your hands and swatting at the ball. Turn your shoulders."

I step behind him, mirroring his posture, and help him to rotate.

"Oh," he says. "OK."

He takes a couple of practice swings that begin to look familiar to me.

It's coming back, Dad,' I tell him now. 'I can see it.'

"And transfer your weight, remember?"

"What?"

"Get your weight moving toward your right foot on the way back, then to your left foot on the way through."

"Oh, yes," he says as he continues to swing, starting to find a rhythm.

All of his motor functions were fine, we were told, and his therapy had been directed solely at his speech. The words were still there, but they needed help finding an unimpeded way back out. His sense of humor, which had never left him even in the most difficult of times, was in hiding as well. Conversations moved too quickly for him. Even if his wit was still intact, he knew enough to understand that the punch lines were coming too late and therefore were better left unsaid. During those first months, he preferred spending time by himself, which was what led my mother to suggest that he try to hit some golf balls.

"Don't be such a lump," she told him. "Go do something."

His first attempt, without me, had been exasperating.

"I'm spastic," he told my mother. "I can't even hit the ball." "Take Philip with you next time," she suggested. "Spend some time with your son."

So that's why I'm here, watching. My father taught me to play not long after he learned the game, taking me with him any time I asked until, like all kids, I preferred playing with my friends. Years later, he taught me how to practice law. Not how to argue or evade or obfuscate issues, but how to get things done for people. And because of him, I was pretty good at it, and I'm sure he thought we would practice together until he retired or died at his desk. The day I told him I was leaving the firm to write novels, he put his hand out to me.

"Good luck, Philip," he said, holding on a fraction of a second longer than our usual greeting or departure. "There will always be a place for you here if you ever decide you want to come back."

"It's coming back, Dad," I tell him now. "I can see it. Last thing, and then I'll shut up: Belt buckle to the target. You're turning back fine, but now you have to turn through."

"OK."

He incorporates this final piece of advice easily into his last few practice swings. I can see his body remembering, and I find myself swallowing hard at the simple beauty of it. Then he taps a ball toward him from the pile.

His stance suddenly looks comfortable, athletic even, for a man in his 70s, and when he takes the club back he turns it to almost parallel, pauses, unwinds and pinches the ball perfectly off the soft turf that is just now starting to dew.

"There, Dad," I say amid the rush of pride. "Feel the difference?"

In the months that follow, my father will gradually re-inhabit his body. He will rejoin the conversation during family dinners, and he'll go back to the office. The same year my first novel is released, my father and his partner will celebrate 45 years of practice together at a dinner party for a hundred people, and he will give a speech that makes everyone laugh. I can't take credit for any of that. His doctors, modern medicine and my mother's dogged patience are what brought him back to us. But this is my contribution, this one moment when his eyes open a little wider than they have in some time, watching the ball rise high, backlit and shrinking quickly against the fading blue sky.

"Yes," he says. "That one felt good."