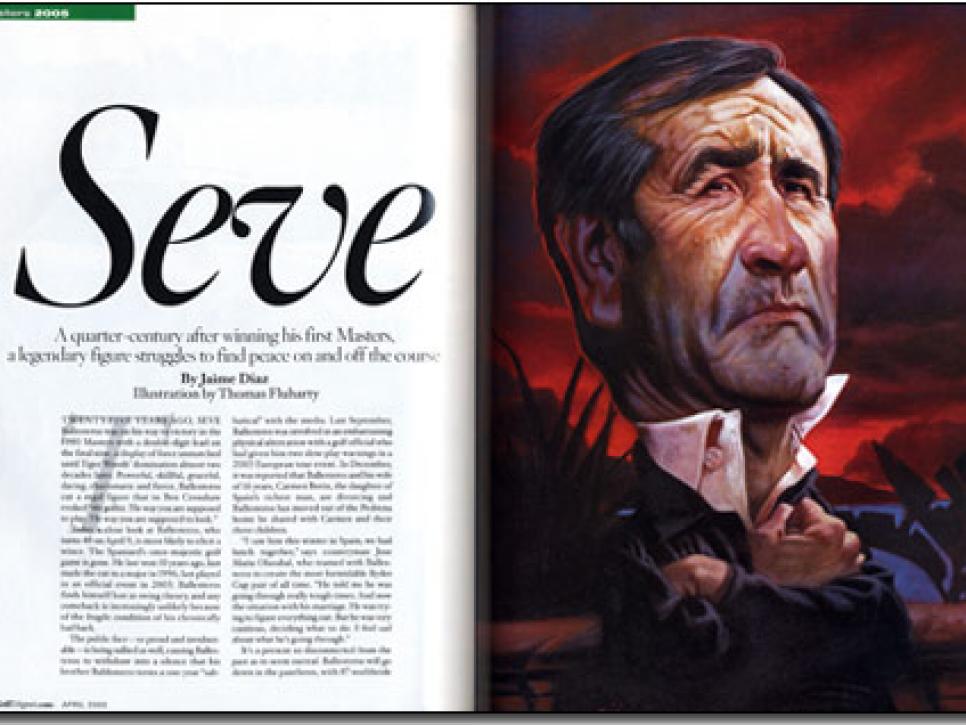

Seve

Jaime Diaz's profile of Seve Ballesteros, including interviews with more than three dozen players and observers who knew Seve, originally appeared in the April 2005 issue of Golf Digest.

Twenty-five years ago, Seve Ballesteros was on his way to victory in the 1980 Masters with a double-digit lead on the final nine, a display of force unmatched until Tiger Woods' domination almost two decades later. Powerful, skillful, graceful, daring, charismatic and fierce, Ballesteros cut a regal figure that to Ben Crenshaw evoked "the golfer. The way you are supposed to play. The way you are supposed to look."

Today, a close look at Ballesteros, who turns 48 on April 9, is more likely to elicit a wince. The Spaniard's once-majestic golf game is gone. He last won 10 years ago, last made the cut in a major in 1996, last played in an official event in 2003. Ballesteros finds himself lost in swing theory, and any comeback is increasingly unlikely because of the fragile condition of his chronically bad back.

The public face -- so proud and invulnerable -- is being sullied as well, causing Ballesteros to withdraw into a silence that his brother Baldomero terms a one-year "sabbatical" with the media. Last September, Ballesteros was involved in an embarrassing physical altercation with a golf official who had given him two slow-play warnings in a 2003 European tour event. In December, it was reported that Ballesteros and his wife of 16 years, Carmen Botin, the daughter of Spain's richest man, are divorcing and Ballesteros has moved out of the Pedrena home he shared with Carmen and their three children.

[Ljava.lang.String;@369dac99

"I saw him this winter in Spain; we had lunch together,"says countryman Jose Maria Olazabal, who teamed with Ballesteros to create the most formidable Ryder Cup pair of all time. "He told me he was going through really tough times. And now the situation with his marriage. He was trying to figure everything out. But he was very cautious, deciding what to do. I feel sad about what he's going through."

It's a present so disconnected from the past as to seem surreal. Ballesteros will go down in the pantheon, with 87 worldwide victories and five major championships, along with being the galvanizing force in the modern Ryder Cup. Conversely, few who were so good have declined so quickly. Ballesteros' final major victory came at age 31, his final win anywhere at age 37.

What threatens to be forgotten is what an intriguing figure he was. "He was almost childlike in some ways, but extremely complex in others," says David Leadbetter. "Intentionally enigmatic," says journalist Robert Green, a longtime Ballesteros chronicler. Ballesteros' legendary impatience kept him from staying with swing instructors long enough for the lessons to take hold, instead leaving him confused and ultimately helpless with a driver. And extreme competitiveness -- Paul Azinger once called him "the king of gamesmanship" -- cost him good relationships with many peers, particularly Americans he faced in the Ryder Cup.

In retrospect, the most telling comment Ballesteros ever made was ignored when his career was in full flight. "The biggest mistake I ever made was to start playing professional golf when I was still only 16,"he said. "I lost all my growing-up years. I haven't lived a normal life."

And, as his friend Lee Trevino adds, "He didn't adapt well to not being king." With no idea if there will be a Ballesteros renaissance on the Champions Tour when he turns 50 in 2007, it would be a shame if this complex icon were remembered as a cartoon character who bludgeoned tee shots into parts unknown and conjured up sleight-of-hand short-game tricks before leaving the grounds smoldering. He was much more. In interviews with three dozen players and observers leading up to this bittersweet anniversary at Augusta National, Ballesteros is remembered as a prodigy, a champion and a mystery.

A YOUNG, COMPLEX GENIUS

Dave Musgrove: I remember seeing this young lad hit balls at Royal St. George's in 1975. He had a short body, and long legs and arms. He stood a long way from the ball to give plenty of room to lash it. He would hit the wild one, but then he'd handle it. I started caddieing for him, and he won the 1976 Dutch Open. Won by eight. He expected to win every week -- he really did. Most really good players think there are weeks when they're not good enough. I remember saying to Faldo, "I thought you were going to win last week," and he said, "No, not playing well enough." But Seve never thought like that back then.

Tom Sieckmann: When I went to play the European tour in the summer of 1977, I hung with the Spanish guys. Seve was guarded with people at first, but then we got along well.

He had this really keen sensitivity for the game -- a savant. He told me he was a great green reader because he learned to putt on the beach with the ball against the white sand, and so he really developed an eye for detail. We'd be way out in the fairway, and he'd say, "Look at the grain on that green." Then one year this eye doctor tested the tour pros, and Seve had something like 20-05, just an off-the-charts eagle eye.

One year at Wentworth they had a one-club tournament for the pros, and Seve shot 34 to win by like five shots. And he had power, miles past everyone else. But his instincts were so good; he knew when to lay off it and hit a soft shot. That was the difference between Seve and Norman, who hit everything hard.

Seve would get wild, but he'd find a way to make it work. He always said, if you want to find out who is the best player, just have a course with no fairway.

[Ljava.lang.String;@4b587235

Dave Musgrove: At first he was just a lad, but he changed. He said himself he was difficult; I would say impossible. He used tremendous energy being intense and angry. It was nonstop from waking up to going to bed. He burned himself out with so much aggravation. Look at the pictures from between the time he was 20 to 30. No one ages that fast.

Some days he wouldn't talk to you at all, and you just couldn't stand it. In those days they paid aggravation money, guys who were hard on caddies, like Stadler and Andy Bean. Seve wouldn't, but I'm proud of my time with him. He could do anything with the ball, and that was a joy.

Vicente Fernandez: We became close, and Seve trusted me to give him some tips. But it's not easy to teach a natural, instinctive golfer. He is very impatient. He wants things right now, all the time. That helped him in some ways, but it also hurt him. The thing I told him when he started going to America was, "Seve, don't read any article about your swing. Don't pay attention. You are a natural player."

PRIME TIME

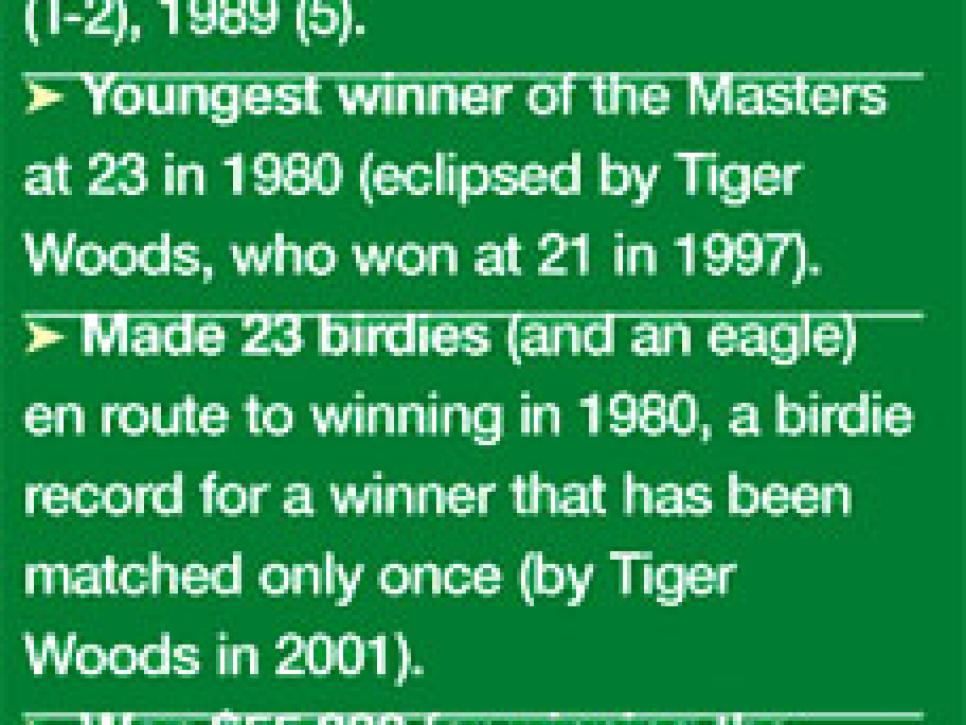

In 1979 Ballesteros won the British Open, and in 1980 he added the Masters. He won again at Augusta National in 1983 and at the British Open at St. Andrews in 1984 to surpass Tom Watson as the best player in the world.

Nick Price: A lot of us who would win majors -- me, Greg, Faldo, Sandy, Langer -- were the same age, but Seve was our benchmark. He won four majors before any of us won any, and he had immense charisma. The way people were riveted to him, he reminded me of Elvis.

Lee Trevino: Seve at his best was the best golf I ever saw. Jack was the greatest chess player ever. He made a plan. Tiger makes a plan. Seve never made a plan, he just made things happen.

He had something we didn't have. He was a much better player than I was. I might have outpracticed him, but I couldn't handle him.

Gary Player: When I holed the last putt to win the 1978 Masters, I'll never forget how he came up and hugged me. You don't see many fellow-competitors do more than say, "Well done." And later he told me, "Gary, you teach me to win the Masters." And in the next five years he won two.

David Graham: To dominate at Augusta as the first European winner [1980], it was like announcing a new era in golf.

When we played together that Saturday, he hit a heel hook on the fifth hole that disappeared into the trees and bushes. We thought it was a lost ball, and he hit a provisional. Somehow the first ball got through everything and finished on the upslope of the sixth hole. I wonder if anyone else has been there in the history of the Masters. He hit a wedge over the trees and made a 5 when he was looking at 7 or worse.

__Jack Newton:__We played together the last day at Augusta in 1980, and he had that glare when you played with him. I used to say, "Don't look at me like that, Seve -- I'll knock you out." All the greatest champions had that look.

Phil Mickelson: I remember I was 9 and watching on TV when he won the Masters in 1980. As he was strolling up the fairway on 18 with this big lead, I remember thinking, I want that to be me someday.

I loved his game. We've played at Augusta a few times, and he's always been very complimentary to me about my hands and short game and bunker play and stuff. He'd watch me and say, "You keep doing that. You keep doing that."

__Hale Irwin:__The fact that Seve might not have hit the ball straight does not mean he was not a great player at the British Open and the Masters. But I always thought it was strange that he couldn't be as precise from the tee as he was from the trees.

__ Bernhard Langer:__ I've seen him when he wouldn't miss a shot, just perfect golf. You don't become the best if you don't have that capacity. It wasn't all scrambling. Larry Nelson:He would try any shot, kind of like Mickelson, but with a much better golf mind.

Rodger Davis: Seve hit the greatest shot I ever saw. It was on the ninth hole at Wentworth in the British PGA. He'd pushed his drive into these thick pine trees with branches that hung within four feet of the ground. Seve got on his knees, and from 185 yards he flew a 4-iron to within 20 feet of the pin. Most pros wouldn't have been able to carry such a shot 20 yards. Magnificent.

Mark Calcavecchia: Seve was on a different level, especially because he did his most unbelievable stuff with a 55-degree sand wedge before everybody started using the 60. He had the flop shot, certainly, but he played a lot of unbelievable chips along the ground. I remember once at Augusta he duck-hooked an iron off the tee at the sixth hole. He's way over there at the edge of the bushes, and he chips this 4-iron up the hill, over all these mounds, and it went in like a six-inch putt. It was like, Are you kidding me?

Lee Trevino: When Seve gave Johnny Miller all that hell at Birkdale [tying Jack Nicklaus for second behind Miller in the 1976 British Open], those English guys started thinking, How can we get this boy on the Ryder Cup? And when they did, Seve -- who always wanted to beat the Americans after he heard they called him lucky -- said, "Saddle me up and get on my back."

Jose Maria Olazabal: I remember playing in the foursomes against Paul Azinger and Chip Beck at Kiawah Island [1991], and on the second hole Seve snap-hooks the ball in the water. We ended up lying like 6 in front of the green, and the other guys are just off the green in two. I told Seve, "Tell them to pick the ball up; there's no point." And he says, "Ssshh. Just wait. Just wait. We'll see what happens. We can hole out, they can hit the chip in the water." That was him.

Fuzzy Zoeller: In our singles match in 1983, he had made great putts to tie me at 16 and 17, and we come to 18 even. I hit a good drive, and Seve blocks it in the bunker. Then he hits the lip with an iron and ends up in another bunker about 30 yards ahead. I put it down in front of the green, and I'm feeling pretty good, although you could never relax against Seve.

The wind's blowing in about 25 miles an hour, and he's got to clear the lip and keep it out of water to the right. Most anybody would have pulled a 6-iron and played short. He pulls out 3-wood. Damn if he doesn't pick it perfect right off the sand and carve this 50-yard slice that carries 250 yards to the front of the green. They say great golfers hit great shots, but that one made me blink.

Rodger Davis: I heard Bernhard Langer say once of Seve that just his posture, the way he walked, looked like he owned everything. When Seve was playing his best, his neck looked about six inches long, he stood so tall. It gave him this intimidation factor. Not many have it -- Palmer and Nicklaus, maybe Floyd. But Watson and Norman and Faldo didn't. Seve, the way he looked and moved, just made you feel inferior.

One time I was playing him in the World Match Play, and I decided not to watch him when he hit, so I wouldn't be affected by his body language. And I actually beat him that day. And afterward he came up to me and said, "Hey, Rodger, why you not look at me?"

Raymond Floyd: Seve was out of that school where he would take advantage of you if you let him. He had this habit of clearing his throat right before a guy started to take the club back, and at Kiawah he did it to Freddy Couples on the second tee. Freddy stopped, and I moved over next to Seve and elbowed him in the side and said, "Seve, that's enough of that." And he didn't do it anymore.

Ian Baker-Finch: I always enjoyed playing with Seve. If he teed off last on the tee, he'd run to catch up with you to talk to you in the fairway. And if he was first off, he'd sort of walk slow until you caught up with him. I really liked that about him.

[Ljava.lang.String;@4ea9e685

Bernhard Langer: We never had harsh words. There was respect, and even advice. I remember in 1980, I was having putting problems, and he came over on the putting green at Sunningdale. He looked at my putter for a moment and just went, "Oh, terrible putter," and walked away. I asked him what he meant, and he said, "Too light and not enough loft." So I'm thinking, This is the greatest player I've ever played with, and he knows things, so I go in the pro shop and find something a little heavier with more loft. I finished second the next week, fifth the next, and then won my first tournament.

But he was difficult to play with. He was always practicing his putting stroke. I would have a putt or chip, and he would be just where you could see him, moving. And you would just get tired of saying, "Move over." Many of us looked up to him, so some of the guys wouldn't even say anything. I don't know if he was doing it on purpose or just thinking he was out of the way, or just too involved in himself.

THE LONG DECLINE

How to explain a sudden loss of confidence and brilliance? It might have started with a bruising failure at the 1986 Masters, opening the way for Nicklaus' sixth green jacket. One more major victory was to come for Ballesteros, at the 1988 British Open, but a crooked driver and the inability to weed out conflicting advice left his game in tatters.

Ken Brown: His loss in the 1986 Masters -- when he hit the 4-iron in the water on the 15th -- was a huge turning point in Seve's career. Up to that point, he thought he could almost will a victory. His father had died the previous month. Before that, I believe he thought of himself as invincible.

Nick de Paul: Seve never took the blame for anything. His attitude toward the caddie was, "You're going to be wrong, and you're going to like it."

I used to try to keep the driver out of his hands; he called me Mr. 1-Iron. And he was a tightwad -- a hard taskmaster, and a poor paymaster. After five years I couldn't take it anymore. You know what, though? I love the guy. It was an honor to go to battle with him. Winning with him at Augusta in '83 was special; winning the next year at St. Andrews was really special. When we see each other now, we hug.

Jack Newton: He was tight with money, but I don't think he played for money. He just loved to win.

Cayce Kerr (tour caddie): Years ago after the Honda, Seve was with his wife and baby son ready to go to the airport to fly to Bay Hill. His caddie, Billy Foster, and I were driving up to Orlando in my van, so when I see Seve waiting for a courtesy driver, I offer him a ride, and he accepts. He was really relaxed, telling stories, joking with Carmen, singing Spanish songs to the kid. When we got there, he offers to pay me and pulls out this thick roll. Real fast I pinch a Benjamin [$100] off the top, which startles the hell out of Seve because I know it wasn't the amount he had in mind. But I'm laughing, and he finally smiles and says, "OK." Billy can't believe it. He tells me, "You wouldn't be able to do that if you worked for him."

Roger Maltbie: When he was rolling, Seve never -- underline never -- suffered from doubt. But it eventually crept in there with the driver. Everyone says, "Putt for dough, drive for show." OK, fine, but really, when you get down to it, the first requirement of championship golf is to drive the ball in the fairway. If you don't do that, all kinds of things have to happen to survive, much less win. You have to get lucky, you have to be good, you have to have an unbelievable short game, and you have to putt like crazy. That can make you old quick.

Peter Alliss: Once you've built your game and you can play, you shouldn't fiddle about with it. Seve had this beautiful flowing action that would produce the odd lateral shot, but there was much more brilliance. You take it to pieces and it doesn't work anymore. The golf swing is like anything -- how you brush your teeth, how you tie your shoes, how you smoke. We all have our way of doing it, and it changes very little.

I remember being captivated by the way Dean Martin held a cigarette. I would try to copy how it fit in his fingers, actually practice in front of the mirror. Never looked right on me.

Tom Kite: What's happening now is so puzzling. We played that "Shell's Wonderful World of Golf" match in Pedrena after the 1997 Ryder Cup, and I've never seen a good player drive it the way he did.

Nick de Paul: Any Tom, Dick and Harry can hit it in the fairway. And Seve, who can do all the genius stuff nobody else can do, can't. That's sad.

Mark Calcavecchia: What's happened to him happens. Some guys get better, like Jay Haas playing probably the best he ever has. But then you've got Duval and Baker-Finch. You just get going bad, you lose your confidence, maybe your back goes out on you, and you're freakin' done, just like that.

I think sometimes, * I've lost my game. I can't play anymore, I can't beat these kids*. Then I go out and shoot a pair of 66s and go, Oh, well, I guess not. That's the way a lot of guys are. It's a fragile, thin line, and if you're on the wrong side of it, man, it's tough.

Ian Baker-Finch: I wasn't as good as Seve, but I was similar. I played the game by feel. When I tried a major overhaul, that's when I lost it. I think that's what happened to Seve.

Craig Stadler: What happened to Seve? I don't know, and I'd rather not think about it. It's kind of taboo.

Nick Price: Seve had an unusual takeaway. His right elbow got away from his body very quickly in his backswing. It created width, but it was a difficult position to recover from. When he was winning majors, he was athletic and supple enough to compensate. It caught up with him later.

Jim Thorpe: Oh, I miss Seve. A lot of people never really got to see him. We played at the U.S. Open in 1985, and his swing was so graceful and solid. But when I watched him a couple of years later, it didn't look as natural. But what the hell is a perfect golf swing, anyway? The thing that hurts a lot of the really good players is they want perfection, and they lose what makes them great.

Jim McLean: One day in the early '90s, Seve asked me to watch his swing and tell him what I thought. It seemed to me that Seve was pretty confused from what I had read, and I didn't want to add to this. I didn't feel like I could be of any help in a quick range lesson. To me Seve had been the consummate feel player who let it all hang out, not a technician or somebody who could benefit from a quick fix.

Dr. Bob Rotella: Once he got to thinking he had to drive it straight to win the U.S. Open and all the technical stuff that goes with that, the game changed. He told me he stopped enjoying it, and he stopped winning.

We always want to explain how very creative people with incredible imaginations do what they do, but we can't. Seve at his best was hard to explain because he didn't do it the normal way. But that didn't mean he needed to change.

Jim McLean: With a huge talent like Seve, conscious thought can short-circuit the intuitive gift. He got with Mac O'Grady, and they had that ritual of burying Seve's old swing in the desert. I thought it was a sad day for golf. I wrote a long letter to Seve after reading that but never got a reply.

Mac knows a tremendous amount about the golf swing, and he's a compelling teacher, but with Mac talking a lot of science and demonstrating, it was a lot for Seve to absorb. Changing Seve was taking an artist and making him a mechanic.

David Leadbetter: In 1991 I saw Seve in Japan, and he asked me to have a look. He had been playing poorly, and his back was bothering him. His swing had a huge turn with a lot of reverse-C, putting a lot of stress on his spine. My suggestion was that we make his posture a little taller and get the swing a little tighter and more compact. The idea was that he might lose some distance, but he would have the ball in play more.

It wasn't a makeover at all, nothing like working with Faldo. His guiding thought was to swing with the feeling of hitting a punch 8-iron. We did one technical drill to help him eliminate the old pattern of a lot of leg drive. Anyway, he won five tournaments before the 1992 Masters.

Before that Masters he came for four days of practice with me. I had never seen him have so much control over the ball, and his iron play was immaculate. On Monday at Augusta, I saw his caddie, Billy Foster, and he said Seve was hitting it fantastic, and he had put money on him.

Tuesday morning I go to the range, and Billy's muttering. He tells me that Seve's brother Manuel had come over, seen Seve doing the drill and said, "What are you doing? This is not you. You are a feel player."

[Ljava.lang.String;@6386aea3

When I walked up to Seve on the practice tee, he didn't even look up. He knew I was there. So I just stood at the back, and I could see that the swing was again a little longer with a little more turn, and he was hitting it everywhere. And I just walked away. And that whole week, he avoided me. [Ballesteros shot 81 in the final round.] He would see me and walk the other way.

Two weeks later we were both back in Japan, and he actually came up and said, "David, I want to thank you for last year. I know I play good, but it's too mechanical for me. I'm a feel player."

And that was the end of it. It was very sad. He was still a young man. I felt he still had a number of majors left in him. It's the biggest regret of my career.

Butch Harmon: In 1995 I stayed with Seve at his home for a week. My whole goal was to get off swing mechanics and be shot-oriented. I'd go out and stand 30 yards in front of him and ask him to hit hooks and slices around me, and he did it every time. I wanted him to see it, feel it, do it. Not think it. We made some progress, but I had to come back to America, and we lost contact.

The big thing with Seve is that he never stuck with one person. He went to everybody and tried too many quick fixes. A swing change takes time. Look at how much time Tiger gives himself. But Seve always wanted it right now, and he got confused.

I found him mostly a charming person, but you look at any great champion, there are a lot of strange things in their personality. They are different. Seve had a little jerk in him, just like Hogan, Nicklaus, Trevino, Norman, Faldo and Tiger. They need that to set them apart from other people.

Tom Lehman: At Oak Hill [1995 Ryder Cup], he played an amazing match. After hitting it absolutely sideways, he still had a putt on the 12th to go 1 down. His whole attitude was, "I don't care if I miss the fairway by 100 yards, this next shot is going to be the best shot you've ever seen."

I'm sure it's very difficult for him to become yesterday's news. It seemed that the way he played was going to be just fine until he started thinking about what he was doing. If I could have given Seve one bit of advice, it would have been to go back to the beach in Pedrena with your 3-iron, stop thinking about it and just start playing. In the match we played in the Ryder Cup, if the shot required any kind of imagination, something you just had to feel and do it, he'd hit a remarkable shot. But put him on the tee or the middle of the fairway and get him thinking about his swing a little bit, it would go sideways.

Ben Crenshaw: When he played his best it was on sheer instinct -- see it and do it.

Randy Peterson (manager of clubfitting and golf instruction at the Callaway Test Center): He came to the test center in 2002, but he didn't want to go on the launch monitor. He said, "My hands are my computer."

In my opinion, what happened to Seve is similar to what happened to Lyle and Olazabal. They all became crooked drivers. Maybe it's growing up in all that wind in Europe, but all three of them pivot around their left leg and hit down steeply.

Bernhard Langer: I told him face to face, "Get one of the best coaches to work for you full time -- you can afford it. Pay him $200,000 or whatever a year for one or two years. Work with only him, groove your technique, and you will be a good player again."

He hasn't done it. Instead, he would be with someone for two months. But once you've played the game for 20 years with a certain swing, you aren't going to change your swing in two months. It's going to take one or two years.

Lee Trevino: Seve always made me think that he was living a few centuries back when Spain ruled the world. He was like a king. But when his game started to slip, he didn't adapt well to not being king. He had always been so confident that no one could beat him, but when guys started to run by him, he lost his confidence.

You know, when you aren't what you were, the thing that keeps you going is the joy of playing. I don't know if Seve has ever really, to tell you the truth, enjoyed it. He loved to compete and win, but I don't know that he loved to just play. And the reason I say that is that when Seve stopped winning, he became a very negative guy on the course.

Vicente Fernandez: I spoke to him just before Christmas. He said he was really working hard, and that he had found some doctors he thought could help him. He said, "Chino, I'm going to see you out there in a few years."

I hope so. But he has to be with somebody who knows about his insides, the way he is, the way he learns best. And then he has to listen. The last time he asked me to have a look at him, I said, "If you're going to trust me, we go. But if you're just going to ask the next guy tomorrow, I won't."

He said, "Chino, sometimes I hate you. Because you know me."