Teen-Ager Ballesteros Takes Aim At The Masters

Dave Anderson's profile of Seve Ballesteros, as he prepared to play in his first Masters in 1977, originally appeared in the April 1977 issue of Golf Digest.

Learn first to pronounce his name properly. Severiano Ballesteros. It's not that difficult. Think of castanets clicking. Sev-uh-ree-AWN-oh BAL-uh-STAIR-ohs. But if his first name is too elusive, just make it Seve. That's "Sevvy" as in heavy -and this young Spaniard is going to leave a heavy impression on golf.

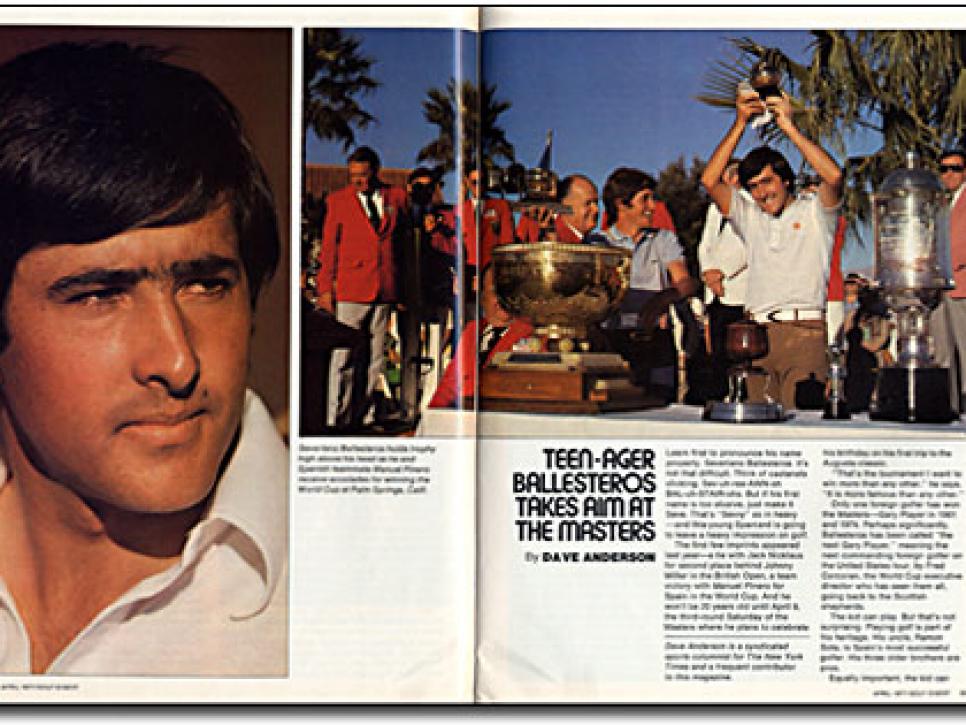

The first few imprints appeared last year -- a tie with Jack Nicklaus for second place behind Johnny Miller in the British Open, a team victory with Mahuel Pinero for Spain in the World Cup. And he won't be 20 years old until April 9, the third-round Saturday of the Masters where he plans to celebrate his birthday on his first trip to the Augusta classic.

"That's the tournament I want to win more than any other," he says. "It is more famous than any other."

Only one foreign golfer has won the Masters -- Gary Player in 1961 and 1974. Perhaps significantly, Ballesteros has been called "the next Gary Player," meaning the next commanding foreign golfer on the Uhited States tour, by Fred Corcoran, the World Cup executive director who has seen them all, going back to the Scottish shepherds.

The kid can play. But that's not surprising. Playing golf is part of his heritage. His uncle, Ramon Sota, is Spain's most successful golfer. His three older brothers are pros. Equally important, the kid can project. He's as tall, dark and handsome as Don Juan, with a smile as broad and dazzling as the Costa del Sol. He has a chance to be the most appealing golfer since Arnold Palmer stopped charging. He is capable of spectacular streaks, not only as Palmer once was, but also at Palmer's expense. Just when Palmer thought he had won the Lancome Trophy tournament in France last fall, the kid exploded for five birdies on the back nine, and won by a stroke.

"I think my sand wedge is very good," Seve says, "but sometimes my putter's good. For nine holes at the Belgian Open, every hole one putt."

Teen-agers putt like that occasionally. They also act their age -- to the gallery's delight. At the British Open last year, Ballesteros rifled a shot out of high grass over a sand dune and onto the green. When the gallery roared, he raised his arms, shrugged and smiled. Instant love. Another time at Royal Birkdale he impaled Pat Ward-Thomas with a pointed index finger when the archbishop of British golf writers inadvertently moved as the Spaniard was about to putt. "No move," the kid scolded, "when anybody putting."

He defends his driving accuracy against those who remember his wristy tee shots into Royal Birkdale's thickets.

"They say I hit the ball left and right but I don't think so. When I go into bunker everybody go click-click," he says, pretending to focus a camera. "But when I'm in middle of the fairway nobody sees the ball"

Johnny Miller saw Seve's ball at the British Open -- on and off the fairway. Paired together, he saw Ballesteros shoot a 73 for a two-stroke lead entering the final round.

"He can win it," Miller predicted. "I'm telling you, he takes a cut at the ball, he just rips it. He reminds me of myself when I'm playing well. But today, I let his scrambling act get to me and my own game went out of control. He's a good kid, though. He wears Johnny Miller slacks."

In the final round Miller shot 66 and won by six shots. Ballesteros had 74 with a birdie-birdie-par-par-eagle-birdie finish after Miller soothed him through a round that might have been 80.

"I know Seve is disappointed," Miller said at the time. "But from my own experience I know this will be good for his career. I know because coming in second at the Masters in 1971 was the best thing that ever happened to me. If he had won the British Open at 19 there would have been all sorts of pressures and demands that he couldn't meet. The best thing for his career was to finish strong. This will be a plus for him, not a minus."

Miller's relationship with Ballesteros has a business link. They have the same manager, Ed Barner of Uni-Managers International, a Los Angeles-based firm.

At the 1975 Double Diamond tournament in Scotland, another Barner client, Roberto de Vicenzo, had been paired with Ballesteros in the team event. Later the phone rang in Barner's hotel room there. "I'm going to do you a favor," de Vicenzo said. "I got a kid who's fantastic. Come down and meet him."

Barner was impressed by de Vicenzo's recommendation. At the Lancome Trophy tournament in France the following week, Barner asked another client, Billy Casper, to scout Ballesteros.

"The kid has one of the finast short games I've ever seen," Casper reported. "And he's an animal off the tee."

[Ljava.lang.String;@6141bf92

Ballesteros justified Casper's assessment of his tee shots. In a group that included Palmer, Player and Casper, he won the Lancome long driving contest.

Although a virtual unknown outside Europe, he joined Barner's stable. He tried for a PGA tow card at the 1975 fall qualifying school but missed by four shots.

On the way to the Japanese tour and the World Cup in Bangkok that year, he stopped in California where, as part of his golf education, he played some of America's best courses -- Riviera and Bel-Air in the Los Angeles area, Pebble Beach, Spyglass Hill and Cypress Point on the Monterey Peninsula. He also signed contracts to endorse golf equipment and golf clothing.

He emerged last year as Europe's most respected golfer with $62,021 in prize money. He topped both the European Order of Merit and the British Order of Merit, won the Dutch Open, the Lancome Trophy in France and the Don Swaelens Memorial Challenge tournament in Belgium, and he finished third in the Swiss Open, the Scandinavian Open and the West German Open. Three other Spanish golfers also won big European tournaments -- Manuel Pinero won the Swiss Open, Francisco Abreu won the Madrid Open and Salvador Balbuena won the Portuguese Open -- but Ballesteros is the Spanish golfer who, because of the British Open, projected himself the most.

He had intended to try again to qualify for the PGA tour in last year's school at Brownsville, Tex., but he competed instead in the World Cup at Palm Springs.

That was after spending a week in Los Angeles being tutored in English-another of Barner's prep courses. Seve speaks English in a charming Spanish accent.

"But please, slow," the 5'-11", 150-pound Spaniard asked American newsmen in the World Cup press tent. "You speak too fast for me to understand."

He understood the Mission Hills course. He shot 289, one over par, while his Spanish teammate, Manuel Pinero, shot 285, three under par. Their winning total of 574 edged the United States team of Dave Stockton and Jerry Pate by two shots.

"I play in the World Cup," he explained, "because if I play in the PGA school, in Spain the people don't like it."

Early this year Seve entered the Spanish air force to begin fulfilling an 18-month military obligation that will limit his tournament appear¬ances for a while. He'll be on leave to play in the Masters and he hopes to get time off in the fall for the PGA qualifying school to try again for a U.S. tour card.

"American tour more difficult," he says, "but more money. Otherwise no difference. Birdie the same, par the same, bogey the same. Out-of-bounds the same."

Seve grew up on his father's small dairy farm near Santander on Spain's northern coast. The Real Pedrena course was a wedge shot away from their farmhouse. "Not many people play golf in Spain," he says. "Bullfighting, tennis, soccer still big but golf is coming up."

The success of his uncle, Ramon Sota, had inspired his older brothers to caddie at Real Perdena, a par-70 of 6,160 yards. Seve followed. When he was 13, he shot a 65, a course record for caddies. When he was 15, he beat his brother Manuel, then a 23-year-old pro. At about that time he accompanied Manuel to a Barcelona tournament. Manuel, now the Real Pedrena pro, was the first-round leader, but soared into the 80s in the second round. He got no sympathy from his younger brother.

"I," the kid snapped, "could have done better myself."

And he soon did. He competed in the Portuguese Open at 16 and in his first British Open at 18, at Carnoustie in 1975.

"I shot 79-80," he recalls with a laugh. "That's one under par."

When he discusses the mechanics of his swing, he doesn't laugh. "It is my swing," he contends. "Maybe it is similar to Manuel's but I don't copy." When Seve finds himself in a slump, he doesn't consult anyone else.

"Just me," he says. "Not even Manuel, just me all the time."

As he matures, Severiano Ballesteros will learn to trust someone else's advice. And as he matures, he will loom as a golfer that all the world will know. When he suddenly arrived at the British Open last year, not even Jack Nicklaus knew much about him.

"I've never seen him play," Nicklaus said.

Jack will see him and so will millions of others. They'll even learn to pronounce his name.