What Hootie got right

We were powerless to stop it.

All we could do was rant and rage.

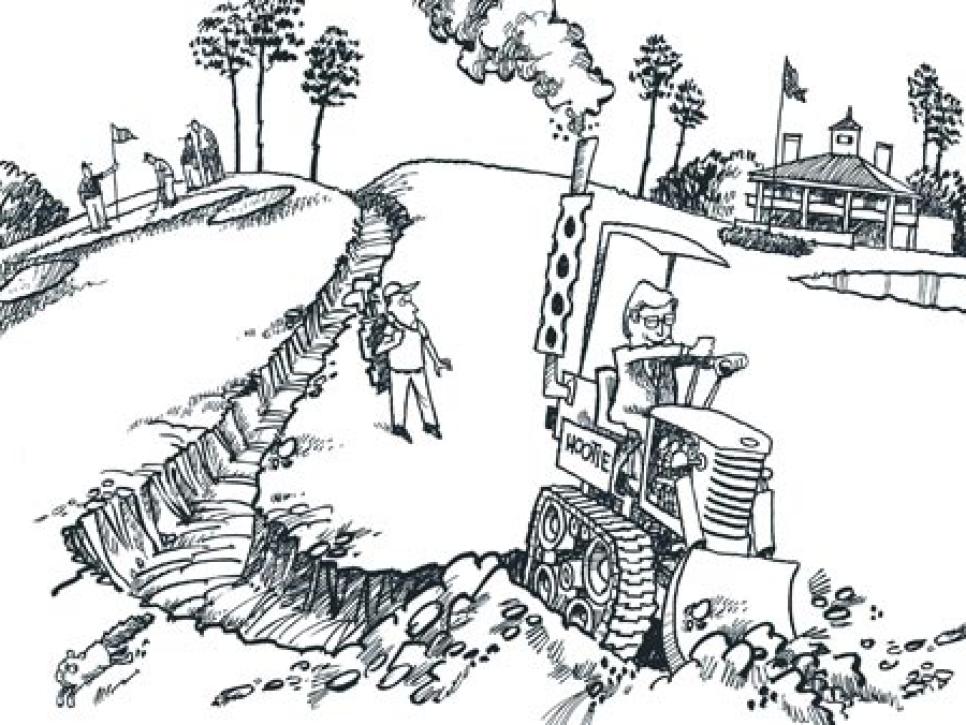

We, a self-appointed, self-righteous cadre of architecture purists, were convinced that the original design by Dr. Alister Mackenzie and Bobby Jones at Augusta National Golf Club needed to be reinstated, not further obliterated. Over the past nine years, each time bulldozers sliced into Augusta National's sacred turf, we were certain they were gouging out another chunk of irreplaceable character, ripping up not just its sod but its soul.

Some blamed architect Tom Fazio, but he was merely an agent of change. Most of us focused our anger at the mastermind behind the makeovers, Hootie Johnson. OK, Hootie wasn't yet chairman in 1997, when Golf Digest/Golf World writer Tim Rosaforte, after Tiger Woods set a Masters record with a score of 18-under-par 270, suggested that maybe the course ought to be "Tiger-proofed." Jack Stephens was chairman then, and he orchestrated the first massive remodeling that occurred a year later, in the summer of 1998, two months after Mark O'Meara's victory.

That's when Hootie became the chairman and club spokesman, and he insisted the changes had been contemplated long before Tiger came along.

To us, Hootie seemed haughty. Asked if players or architects were consulted before any course changes were implemented, he answered, "No, no players were consulted. Only Tom Fazio. We didn't consult him; we worked with him."

We blamed Hootie because, by reading between his lines, we could tell he was directing that holes be stretched to excess, trees planted in unprecedented numbers, and bunkers relocated and deepened. Because of him, the Masters, which used to come alive on the back nine on Sunday, seemed to grind to a halt on the final nine.

What we purists found particularly galling was that Hootie justified repeated radical remodelings as faithful to the memory of the original designers.

"As in the past, our objective is to maintain the integrity and shot values of the golf course as envisioned by Bobby Jones and Alister Mackenzie," he said in 2005.

At the time, those seemed like fighting words. Today, almost two years after Hootie stepped down, replaced by Billy Payne, they seem like a pretty accurate summation of Hootie Johnson's tenure.

Yes, this purist has experienced an epiphany.

Hootie got it right. Mostly.

I base this not on the fact that the past four Masters have been thoroughly engaging -- two wins by Phil Mickelson sandwiching Tiger's playoff victory over Chris DiMarco, punctuated by last year's surprise, Zach Johnson, who outplayed Tiger on the final nine.

No, I base it on a lot of research into what Mackenzie and Jones intended with their design of Augusta National, and particularly on three long-forgotten Augusta Chronicle newspaper articles Jones wrote in early 1951, a most enlightening and persuasive series describing the reasons for many of the changes that he and then-Masters chairman Clifford Roberts approved and implemented between 1937 and 1950. (During research for a project on Augusta National, I'd discovered that articles from 1951 were missing from the online archive but found the series on microfilm during a visit to the Augusta library.)

Yes, as we've documented through the years, Augusta National has been a constantly evolving golf course. But what we've discovered explains why the much-vilified changes made in the past decade were really in keeping with the long-standing strategic vision for the course.

So Hootie wasn't blowing smoke when he said in 2001, "Throughout their tenure, Cliff Roberts and Bob Jones made improvements to complement the changing state of the game. We have continued this philosophy."

Was the doctor on the course?

Very little of Alister Mackenzie has survived at Augusta National. Everyone agrees with that premise. But I'm no longer sure how much Alister Mackenzie ever existed at Augusta National.

The man visited the site only twice in 1931, in July and October. Once construction started in February 1932, he spent part of March and April contouring the greens, then left, never to return. (Perhaps the fact that the club owed him $3,000 of his $5,000 design fee influenced his decision.) The course was playable by September 1932 and officially opened in January 1933. Mackenzie died in January 1934, two months before the first contestants teed it up in an invitation tournament that would become the Masters. (It was contested in late March that first year.)

Purists have latched onto a single article about Augusta authored by Mackenzie in the March 1932 issue of The American Golfer magazine. (It was later reproduced by the club in a booklet titled "Description of the Bobby Jones Golf Course.") That article, written at the start of construction, and a couple of routings and preliminary hole-by-hole green diagrams, are the only surviving expressions of Mackenzie's design.

Mackenzie's article mentioned that, though he and Jones weren't trying to duplicate famous British golf holes, they wanted 18 ideal holes, and Jones thought the Old Course at St. Andrews most closely approached his ideal. Purists jumped on that, and have long insisted Augusta National was patterned after St. Andrews: enormous fairways, few trees, hidden hazards, humps, bumps and mounds, big greens with bold contours, all playable with a bump-and-run ground game.

Well, yes, it started out with some of that. But most of that was removed within a few years of its opening.

Here's Bob Harlow (later the founder of Golf World magazine) writing in The Augusta Chronicle in 1938: "A British linksland motif which was intended by the original builders of the Bobby Jones golf course in Augusta has been abandoned, and the artificially thrown-up sand-dune formations which were intended to give the foreign touch to a number of the greens at the home of the Master's [sic] tournament have been replaced with a more modern American concept of proper contours to test a player's skill. . . It was a notable experiment, but an effort to duplicate the natural terrain of one country in another location, by artificial means, does not work out successfully except in Hollywood."

Think Bobby Jones wasn't involved in that transformation? Think again. In his 1951 series, Jones explained his reason for abandoning the Mackenzie green on the par-4 seventh, a green inspired by the Valley of Sin at St. Andrews' 18th. "The contouring of the green in its final form did not correspond with our original objective," he wrote. "The contouring of the original green was too severe, or if you choose, too tricky."

Length and width

After watching Jones and Mackenzie stake out the course, longtime Jones biographer O.B. Keeler wrote in 1931, "The Jones idea and, I believe, that of Dr. Mackenzie also, does not incline to drive-and-pitch holes." Only two on the entire course, Keeler reported.

So Jones would not have approved of modern-day players hitting 300-yard drives, then pitching wedges into half the par 4s on the course. Hootie was right in lengthening so many holes. For example, the first from 410 yards to 435 yards, and ultimately to 455; the 17th from 400 to 425 yards and then to 440; and the 18th from 405 to 465. Each time, each hole was lengthened by adding another new back tee (stretching the course to 7,445 yards today, up 520 from the 6,925 in Tiger's record-setting year).

Bobby Jones lengthened holes, too. But he did it by moving greens. So much for retaining the integrity of the original design.

Take the green at No. 7. Jones thought the then-340-yard seventh was a "pitch and a kick." (In 1937, Byron Nelson drove the green; today the hole is 450 yards.)

"The original hole by championship standards played too short," Jones wrote. He adopted suggestions for what became the present seventh green, relocated atop a hill, " . . . a new postage-stamp type of green, almost entirely surrounded by bunkers, the only green of this type on the course."

(Of course, these days dozens of golfers can drive it 340 yards. Some players, particularly six-time Masters champion Jack Nicklaus, have long advocated a reduced-distance golf ball to preserve older classic courses. In 2002, Hootie intimated that the club was considering requiring all competitors to play just such a "Masters ball," but nothing has come of it, probably because the club doesn't want to interfere with players' individual equipment contracts.

Ironically, back in November 1933, Bobby Jones hosted a weekend of golf at his new course for players who represented Spalding golf equipment. They all played 36 holes using the same golf ball, a prototype "Tournament Spalding" ball. That's likely the only time an event at Augusta National involved just one type of golf ball.)

The par-3 16th was originally 145 yards over a ditch, a popular birdie hole for the members, especially Clifford Roberts. Several Masters competitors told Jones the hole didn't measure up. In 1947, the present 16th was created. Again, a heaving, rolling Mackenzie green was abandoned, in favor of a new one positioned in a different direction, at the far end of a newly formed pond, 190 yards (now 170) from the tee.

"The expanse of water seems to have reduced the birdie harvest," Jones wrote. "Everyone experiences a bigger thrill in playing the present hole. Most certainly, it is far more attractive and exciting than the older one." Jones also described the remodeling of the par-4 10th.

"Originally the green was located at the end of a downhill slope in a miniature amphitheatre. Although the championship length was 430 yards, it played too short because of the terrain. . . . In 1937, a new green was constructed thanks in part to the generosity of a club member from New Jersey. It is farther back, to the left and on higher ground [turning the greenside bunker, the only remaining Mackenzie bunker on the course, into a fairway bunker today]. The maximum tournament yardage is now 465 yards [495 yards today], but if a good tee shot is played down the left side of the fairway, where it takes full advantage of the downhill roll, the expert can reach the green with an iron second shot."

That last sentence is particularly telling, for it dispels the notion that Jones intended every green at Augusta National to be approached from a variety of angles from different positions on mammoth fairways. He was dictating where golfers needed to drive it on the 10th hole if they wanted to reach the green with an iron.

At the time the 10th green was relocated, the ninth green was reshaped. Jones didn't address that change in his 1951 series, but O.B. Keeler did so in July 1937: "The ninth green has been contoured all over and the bunkering plan altered to discourage heartily the fancy of some smart competitors of yesteryear for driving over into the No. 1 fairway and approaching the ninth green from that angle. They will play it as the doctor ordered from now on."

But Bobby Jones did intend some holes to allow options in angles of attack. What required thinking and finesse, he wrote, "was the contouring of the greens. They were undulating to the extent that it was hard to get close to the hole on some pin locations, unless the approach shot was made from the correct angle. Another interesting feature to us was the requirement for a run-up type of shot on several holes."

The narrowing of fairways by the introduction of even light rough, and especially by the planting of mature pine trees, would seem to fly in the face of this particular shot value.

Fazio, consulting architect to Augusta National in recent decades, usually declines to speak on the record about any changes to the course. But last year, when told of Jones' article -- and about the specific language regarding approach angles -- Fazio couldn't resist.

"Why would we redesign a course for a game that nobody plays anymore?" he said. "Nobody hits fades or draws to certain spots in a fairway. They bomb it. They hit it very long, they hit it very straight."

Hootie Johnson, no doubt in deference to Payne, declined to comment, and in response to questions for Payne, the club replied, "The changes made to the golf course, including the addition and subtraction of trees and the defined second cut have not eliminated preferable angles for the players. The state of golf today must be taken into consideration. Historically, bump-and-run shots, balls hit with low trajectory and Bermuda greens made playing the angles more prevalent. Today, the game is different. Ball flight, how it spins, its trajectory and grooves on clubs have changed how people play this golf course. Players don't play the angles anymore to the same degree that was done in Jones' day. It's also important to remember that this course has always had some rough and that trees have been planted for a very long time."

If there's one thing this purist doesn't think Hootie got right, it's the removal of previous tees when new back tees were constructed. (OK, it turns out that had been the practice at Augusta National as far back as 1970, when superintendent Al Baston had his father, a local contractor, build a new back tee on the par-5 15th.)

Whoever was originally behind the decision should be ashamed. Augusta now has only two sets of tees, one at the championship's 7,445 yards, the other for members at 6,365 yards.

Fans cannot view the spots from which Hogan and Snead, Arnie and Jack, teed off. Players can no longer play the course from those spots. Those tees don't exist. They've been blended into the landscape, as if they never existed.

The club has plotted those previous tee positions on a GPS system and could locate precise spots where a plaque could be inconspicuously installed to mark, say, the location of the 11th tee when the hole was the conclusion of three dramatic sudden-death playoffs in four years.

But that's ancient history.

Augusta National has never been interested in ancient history. Not even in the days of Clifford Roberts and Bobby Jones.

In the fourth round in 1935, Gene Sarazen made his remarkable double-eagle 2 on the par-5 15th. It gained him a tie with Craig Wood, whom Sarazen defeated in a 36-hole playoff the next day.

The day after the playoff, Sarazen asked his caddie whether he'd heard of any plans to install a plaque on the spot at the 15th where he'd made his historic swing.

"Mr. Gene," the caddie said, "they went down there this morning and sprinkled a little rye seed in the divot and covered it up."