Perfectly Padraig

Looking back, so many things were perfect.

Starting with the putt. No, starting with the pitch. No, starting with the place, Carnoustie in Scotland. No, starting with three places: Carnoustie, Largs and Dublin. No, starting with the Scottish swing doctor Bob Torrance and the American "head" doctor Bob Rotella. No, starting with Jean Van de Velde in 1999. No, starting with Ben Hogan in 1953. No, starting with Padraig Harrington, himself, a broken-hearted amateur standing hollow-eyed on the same spot at the age of 18. No, let's start over.

At the end.

"When the playoff was done and I had won the Open Championship," Harrington says, "I had the momentary celebration you always have, and then I looked around and saw Sergio. I'm not great when it comes to faces and reading things like that. But I never saw disappointment as clearly as I could see it in his face at that moment. I felt for him. Really big-time. I did the cursory things that we all do as golfers. Commiserated. Shook his hand. 'Hard luck. You'll have your time.' I did it with as much heart as I could, but I'm not really the person for that. No player is. Only your family, only someone who truly loves you, can possibly say anything that might help at a moment like that. You know, Sergio played professional golf before I did, and I'm eight years older. He was just 14 -- we were both still amateurs -- when I first played with him at a tournament in Spain. He was the coming sensation."

Long before that, Harrington remembers following a group of Spaniards around the Stackstown Golf Club in Ireland, figuring them for more than a few lost balls. "My very first tournament," he says, "I played with the same Titleist golf ball for 54 holes, one I found at Stackstown." When you win the Open, you can't help but spin backward a little.

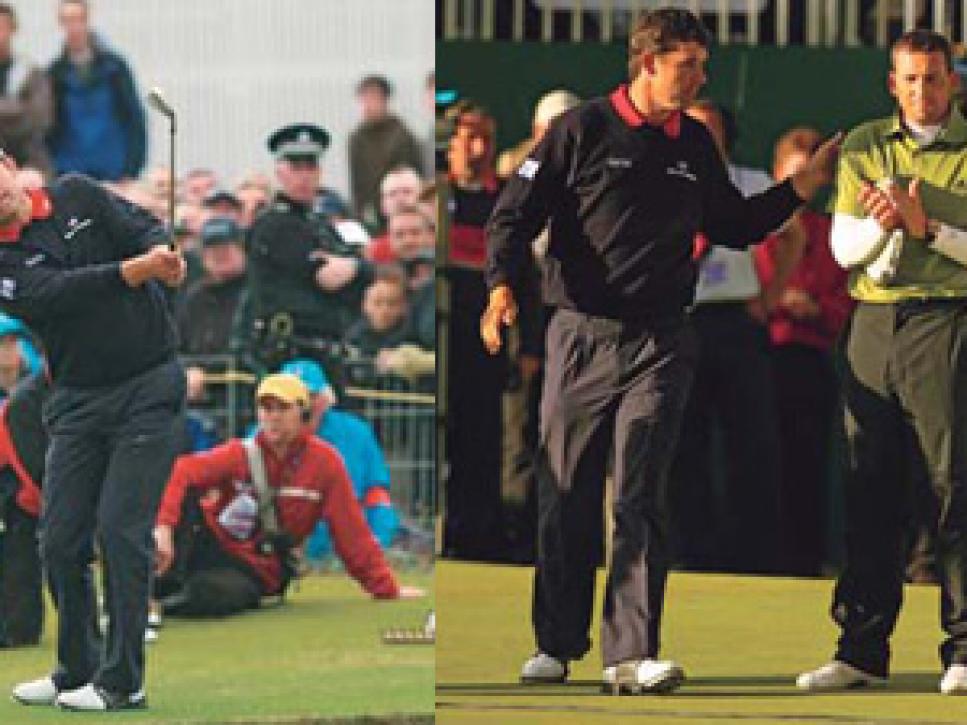

Before becoming the Champion Golfer of the Year, of course Harrington hit two balls into the water on the 72nd hole. For just the chance to play off against Garcia, who led him by six strokes that Sunday morning, Padraig had to get up and down for a double bogey, pitching over a burn. Not much more than a chip, actually. But the spectators reacted at impact as if he had dropped a pile of dishes.

"I enjoyed that," Harrington says. "Everybody thought I had struck it too hard. I think I laughed. As I hit the ball up in the air, I listened to the crowd go, 'Ooh, it's going too far! No, it's going to spin! It's going to spin! It's going to stop! It's going to stop!' I got such a charge out of fooling everybody. I was a kid again back at Stackstown, competing against the other kids, closest to the pin for a plate of chips and a dogwash."

STACKSTOWN

A dogwash is a drink. "The lowest form of drink," Harrington says, "a lemon cordial and lime concoction that the barman named 'dogwash' because he had to make so many of them all day." The morning after Harrington delivered pretty much all of Ireland indoors, he returned to the little "guards" course in Dublin, which his father and nine other cops built by bare hand and shovel. "One of my earliest memories was at 4 years of age," Padraig says, "helping to level a green with my feet. I was lucky. My four older brothers had to pick up stones. When I brought the claret jug to Stackstown, a junior event was on. The TileStyles tournament, my first big competition. I was coming around full circle."

On a subsequent junior day, a stern "No Slow Play" sign and a gentle head pro, Mike Kavanagh, are keeping things moving. It's a chilly Thursday. A tall young woman named Cliodhna McCarthy, wearing wire on her teeth and a down vest, says, "I had my picture taken with Padraig that day he was here. We all did. He's a lovelier man than you can hardly say. He wouldn't be telling anyone he's brilliant or anything." Cliodhna has just turned 16.

As formally as diplomats, three considerably shorter boys shake her hand and thank her for the game. One pulls out a cell phone and calls his mother straightaway. "You won't believe it," he whispers. "I played today with the girl who won the Irish Open last year." True enough, Miss McCarthy took home a silver spoon. It was a handicap tournament, however. She played off a 36.

In the vestibule of the clubhouse, name tags aren't needed to pick Padraig's father out of the photographic lineup of the founding coppers, and not just because his jaw is set exactly like his youngest son's. The eyes are equally telling. The rest of the hard men on the wall have the look of policemen everywhere, that glint of cynicism from spending 30 years being lied to every day. Padraig's father is the only one who doesn't look like a policeman.

"My dad was the worst policeman who ever stepped foot on the job," Harrington says affectionately. "I don't think that man ever served a summons in his entire life. My mum says he gave taxi fare to more drunks, and stopped more people from being arrested, than any lawman who ever lived. One of our top Irish athletes pulled me aside recently to tell me that, when he was young, my dad could have arrested him but didn't. Instead, he kicked his backside and sent him home. Dad was too soft to be a policeman, really."

On the subject of drunks, there is just a shadow of drink in the picture on the wall. Maybe it helps explain the improbable, not to say, incredible fact that Ireland's hero of the moment is a teetotaler.

"My father never drank the last 30 years of his life," Harrington says.

"I would suggest that drink probably wasn't the best thing for him. But I'm a teetotaler for the simple reason that I don't like the taste of it. I never have. I'll take a celebration swallow, but I couldn't drink a whole beer."

Besides the taste, there is another reason. "In the amateur game," he says, "I noticed right away that the players who drank -- some of the most talented guys -- did it to wash away expectations, as a kind of built-in alibi. 'I didn't win my match today. Well, I had six pints last night.' They didn't care for the stress. It was a way out, really. I see a little of that in the pro game, too."

Gazing through the window of his shop, Kavanagh points to the spot where Padraig used to hit balls with his father standing alongside. "Practically in the dark," Mike says, "sometimes with sleet coming down sideways. As we say in Ireland, you wouldn't put a milk bottle out. I'd be locking up. But I couldn't stop looking at them. I'd watch them by the hour."

"My dad retired when he was 50," Harrington says, "so we had the next 20 years together. Always just the two of us on the range. I practiced in conditions that were positively silly. It couldn't have done me any good in terms of swinging a golf club. But it was quite good in terms of developing character, and it brought me close to my dad."

Photos: Darren Carroll/Charles Laberge

Padraig is "very fearful of parents who push their kids" and grateful that his father carried his own athletic identity. "In the county of Cork, I'd still be referred to as Paddy Harrington's boy," he says. For a time, though, the father's Gaelic football record haunted the son. "My dad lost two All-Ireland finals, the equivalent of Super Bowls in America, and yet he had absolutely no regrets. He was content with both second places." For a long time, Padraig seemed to specialize in them, too. "Am I the same? I asked myself. I worried about that."

But as he came to understand the peace his father knew, he began to develop some peace of his own. "The best story to sum up my dad is that he boxed in the guards and won the national title for his weight limit. The guy he beat in the finals was badly out-classed but just wouldn't go down. My dad hit him, and hit him, and hit him, and hit him. The guy was determined not to fall. Dad won comfortably on points, but he felt so bad about the beating he gave this guy, he never boxed again. That's the only trophy of his at home that I want to have someday. I've told my mother that."

Breda Harrington might be the most competitive Harrington of all. A nongolfer when the boys were young, she banned all talk of it from the dinner table. But then she took up the game herself. "Embarrassed to have anyone see her in the learning stages," Padraig says, "she would steal away with me to a public par 3. Then, finally, she was the one who began bringing up golf at the dinner table. We all laughed."

Tadhg, Columb, Fintan, Fergal, Padraig. All boys. "Like most families," Padraig says, "Irish families, Catholic families, the first kids go out to work, to help make money. It's the last kid who gets all the opportunities. It's funny, but growing up, I always thought I came from a wealthy family. Because my brothers gave me so much. All four of them had real jobs, while I hawked and sold golf balls for my pocket money. Every Friday, after they drew their wages, they'd take me down to the shops and say, 'What is it you'd like?' "

"We've always treated him like a little brother; we always will," says Tadhg, a former cop turned legal bookmaker. " 'It's lucky you can hit a 3-iron shot over the water,' we'll tell him, 'because you can't do anything else.' He's just an ordinary guy around us. He's an ordinary guy around everyone, but especially us. He's a very kind person, you know. He calls our mum every day. He calls me almost every day. I give him some stick. He takes it. He knows we're all as proud of Columb the businessman as we are of Padraig the golfer. That's the way he wants it, too. Not that we allow him much say in any of these matters."

Padraig never had a golf lesson until he was 16. He is a natural product of Stackstown and its 100 slim acres. "There wasn't space in the practice area for towering iron shots that stayed up in the air for eight seconds," he says, "but the tightness of the course and the range gave me other strengths. Of course, I was always a guy who didn't take much notice of my strengths because I was too preoccupied with my deficiencies. I didn't expect ever to be a star in the game of golf. I was never destined to be a star. I didn't have the swing for it. Everybody said so."

He was the best boy golfer in Ireland at 16 and 17, the country's best youth golfer at 19 and 20. "But I never played in a pro event as an amateur," he says. "That should tell you something. I was never the one the whole country was looking at." After hanging around the amateur game long enough to staff three Walker Cups, he turned pro "basically because all of the guys I was beating were turning pro."

In Harrington's first professional tournament, he tied for 49th and won £1,865. "I rang my mother," he says, "and told her, 'Mum, they're giving it away. Forty-ninth. It's possible that I may need a wheelbarrow someday.' "

From the generation ahead of him, both Des Smyth and Eamonn Darcy use almost identical words to describe the young pro. "He never stood out as a ball-striker," Smyth says. "Nobody ever commented on his ball striking," says Darcy. But they finish up with the same phrases, too. "Highly motivated," Smyth says. "Amazingly hard worker," Darcy says. "Tough," they both add.

Padraig, who will be 37 in August, says, "I've spent years trying to explain this to people. I just never looked like a great player. I grew up on a very tricky, winding golf course where the whole idea was to get the ball on the ground as fast as possible. Make sure it's moving in the right direction, and you're fine. I was a good chipper and putter who tended to be short and straight. I had to be the most frustrating young golfer to play a match against because I didn't look like I was anywhere near good enough, even to me."

There are two Irelands, of course. Two golfing patriarchs (Fred Daly and Christy O'Connor). Two contemporary stars (Darren Clarke and Harrington). "Darren was the big boy when I came out," Harrington says. "Those were competitive times. I was trying to catch him." The more natural player, Clarke says, "Padraig and I were diametrically opposite, chalk and cheese. Golf always came relatively easily to me. He showed up with a great short game and a not-so-great full swing. I never had to work as hard as Padraig." (Clarke is not a teetotaler.) For a long time, Darren was the chalk to join Daly (Hoylake, 1947) as just the second major champion in all of Irish history. Darren reached the brink a couple of times. But his wife died in 2006, after several cruel sieges of cancer, and his game wasted away, too. He tumbled down the World Ranking to 247.

"Darren will return to form; I'm sure he will," Harrington says. "I don't think my victory has set him back at all; I think it will prod him forward. And I think it's great that Ireland has two totally different characters who, incidentally, are quite happy to be different. It may be the reason we get on so well." Clarke says, "I'd be lying if I said his success hasn't given me an extra incentive. He's clearly the best Irishman at the moment. I'll be trying to challenge him in the future."

Regularly Clarke takes his sons, 9-year-old Tyrone and 7-year-old Conor, to visit Heather's grave. But it was on one of the trips he made alone that he found a bouquet of flowers and a note from Padraig and Caroline Harrington.

On both sides of the Irish divide, golfers have been standing up. Rory McIlroy, an 18-year-old Ulsterman, was a leading character and the low amateur at Carnoustie. Opening with a 67, Paul McGinley had a speaking part throughout."I knew Padraig first as a Gaelic footballer, a goalkeeper," says McGinley, fellow Ryder Cupper, "when I was about 14 and he was maybe 11. We lived within a mile of each other. He had a goalkeeper's gnarled fingers, pointing every whichaway. Take a look at them sometime. As golfers, Padraig and I were always friendly enough but never close, until we paired together to win the World Cup in 1997."

At the reception back in Ireland, Harrington interrupted his speech to look over at Paul and say, "We're bonded forever now." "And, you know, we are," McGinley says. "He was right. I know his mother. I knew his father well. Lovely man. Great footballer. My own father used to talk about him."

Paddy Harrington died of cancer in 2005. At Carnoustie, so many people said to Padraig, wasn't it sad his father wasn't there to see him become a major champion? "Well, this is my answer," Harrington says. "I totally believe he was there. He was. Do you know the biggest thing I miss about my dad? Ringing him after a round of golf. At the Irish PGA the week before, the spectators got to walk in the fairways, and every time I turned around I expected to see him."

LARGS

On the Ayrshire Coast of Scotland, north of Troon, in the salty town of Largs, Harrington's other father is at work as usual. Like a chess master simultaneously taking on all comers, he moves up and down the practice tee instructing a postman, a pro and a teenage boy, all the while chain-smoking cigarettes and chain-drinking cups of cappuccino. Bob Torrance has hundreds of surrogate sons, and one real one, Sam, but Harrington is the only adoptee with his own brass bed in his own room in the Torrance home, the Ben Hogan suite.

"Every room in that house could be called the Ben Hogan suite," Padraig says. "His picture is everywhere." Maybe that was the foundation of the perfect week. Harrington thinks so. "Bob is the all-time Hogan disciple. Look at all those photographs, every one of them signed by Ben. [To Bob Torrance with all good wishes and for better golf. Ben Hogan.] So where was this Open being played? At Carnoustie [the only Open venue Hogan ever played, the only Open Championship he ever won.] Was that not perfect? From there you move on to the writers' dinner on Tuesday night."

Torrance was the honoree; Harrington introduced him. Neither of their talks contained a flowery phrase. But both addresses were models of authenticity and affection. And there was a grand moment in the middle of Torrance's speech, when he left the podium, kissed his wife, June, and returned. "That's not just the most romantic thing he's ever done," she said. "It's the only romantic thing he's ever done."

Perfect. "I was thrilled," Harrington says. "The newspaper guys have always been his mates. Bob reads every word. Through the years, he's given all of them a lot of words, just like he's given something to everyone in golf. I've never gone to that tee in Largs when there weren't three or four lads hitting balls. And he's got great hopes for all of them. One of them pays him with coffee and scones, another with crops from the farm. Bob wouldn't take anything at all, but they like him so much that they make an effort."

Seventy-six years of age, with a haircut that's a tight gray lie and a sun-baked face that falls in folds like a basset hound's, Torrance preaches Hogan all right, but there's more than a touch of Harvey Penick there, too. "Harvey's teachings were simple," Bob says. "They should be. Golf's hard enough. At the same time, if you learn something too quickly in golf, you'll lose it too early. Padraig came to me after I had worked with Paul McGinley for a few years, and the only thing of Padraig's that I never changed was his grip. His leg action was especially bad. You might have noticed, it's better."

The pro on Torrance's tee is Raymond Russell, who had a piece of fourth in the 1998 Open but like everyone, including Harrington, still has to trudge out on the pasture and retrieve his own golf balls. "Bob doesn't use a video camera," Russell says. "He just watches. He doesn't have an infrared heater to keep warm. Just a hundred coffees. 'Now go pick up the balls,' he'll say, 'and when you come back I'll show you something.' The thing he'll show you leads to another thing and another thing. It starts to become a chain reaction. Doing this, this and this almost forces you to do that, that and that. And then he'll smile."

"No matter what you do in life," Torrance says, "helping people is the greatest satisfaction there is."

"You didn't stay for the sole? June's Dover sole?" Harrington says, appalled.

"Well, you missed a tremendous opportunity. Though it's probably just as well. When you've had it there, you can never enjoy it anywhere else. It's like having fish that's just come off the trawler. Absolute perfection."

Photo: Darren Carroll

CARNOUSTIE

Bob Rotella, Harrington's psychologist, author of Golf Is Not A Game Of Perfect, had no place to stay in Carnoustie. "I told him, 'You can stay with us,' Padraig says. 'We don't have room for Bob,' Caroline said. 'There's Patty [their 4-year-old son], there's your mother, there's the nanny... "I don't care," I told her. 'Bob's going to stay with us.' "

Throughout the week, their talks about golf, not just the psychology of golf, lifted Harrington. "I love golf," Padraig says exactly the way Robert Redford spoke of baseball as Roy Hobbs. "I can talk about golf all day and all night. It must be the best game in the world that way."

"We went over our basic stuff that we go over all the time," Rotella says, "but on Wednesday night he wanted to get into an in-depth conversation on the mind and golf, and I basically shut him down. 'Let's do that next week,' I said. 'I like where your head's at right now.' Just before the opening bell, it's always tempting to start picking your game apart. But it can be self-defeating. Padraig's gotten a lot better at working against that. He had played so well in the Masters [tied for seventh]. He already had a lot of peace of mind. He was about as decisive as I've ever seen him with his long game. A lot of the other players were talking about that."

Every day at the 18th, Padraig and his caddie, Ronan Flood, stuck their fingers in the eyes of hobgoblins. "There's my old divot," Harrington would say, referring to a ball he hit out-of-bounds in the British Amateur of 1992, his worst moment on a golf course to this day. Every day of the Open, including the last, Padraig brought up Jean Van de Velde's notorious triple bogey. "It seemed to me," Rotella said, "that all of the players were bringing up Van de Velde in practice rounds. 'By the end of the week,' they all seemed to be saying, 'Van de Velde might not feel so bad.' "

"After going in the water twice," Harrington says, "I definitely thought about that. I actually said it out loud. 'Van de Velde made 7, Ronan. Let's make 6.' "

A pitch and run would have been an easier shot. Harrington wouldn't have had to strike the ball perfectly to get away with that. "But I said, 'Let's go with the higher-difficulty one, because I know that one. It's me. As I told you, it may have been the most routine shot I ever struck on a golf course."

The five-foot putt wasn't routine. As Padraig read it, "Outside left, miss. Outside right, miss. Center of the cup, miss. Left half of the cup -- that was the only line." Maybe it's better when there's only one way to make a five-footer.

The first time young Patrick ran to his father on the 18th green (precisely one hour and 29 minutes later, Patty would do it a second time, a record that will never be broken), Harrington flashed the most amazing smile. "I saw the replay of that just yesterday," he says. "There's a man who has just taken 6 on the last, maybe to lose the Open, and he has the biggest smile. I won't deny there was an element of disappointment at that instant, but it was overwhelmed by the sight of Patty and this feeling inside that told me, It's not over yet."

He has a little of that feeling now. "Golfers won't usually state their ultimate goal," he says, "but I'll tell you mine. Here's what it is now. Here's what it has always been. Not to be someone who became as good as he could possibly be, but to be someone who tried to be as good as that. If I try as hard as I can, and it doesn't quite get me there, the trying is the main thing." Turning to Kipling, he adds, "I'm very aware of the twin imposters, success and failure. Sergio's putt drops on the 72nd hole, and we're telling a different story today."

At this point, in a Boston motel room, young Patrick has decided the interview is over. "It's time for hugging," he says, jumping on his father's head. "Patty is the world champion hugger," Padraig explains technically. "Get down, Patrick!" shouts Caroline, more pregnant than a pause. "I mean it, Patrick! Right now! One, two..." She doesn't get to three. A picture pulled out of a wallet distracts the boy. It's a photograph of a little girl holding a baby in a basket. "I'm getting one for Christmas," he says.

To carry away all his riches, Harrington will need a very large wheelbarrow.

"I don't understand why they pay first-place money," he says. "You don't have to pay first-place money. They should pay second place on down. Who needs to be paid for winning?"

It turns out, Padraig had been playing for history all along.

By the way, Patty got his Christmas present, Ciaran, another boy.

.jpg)