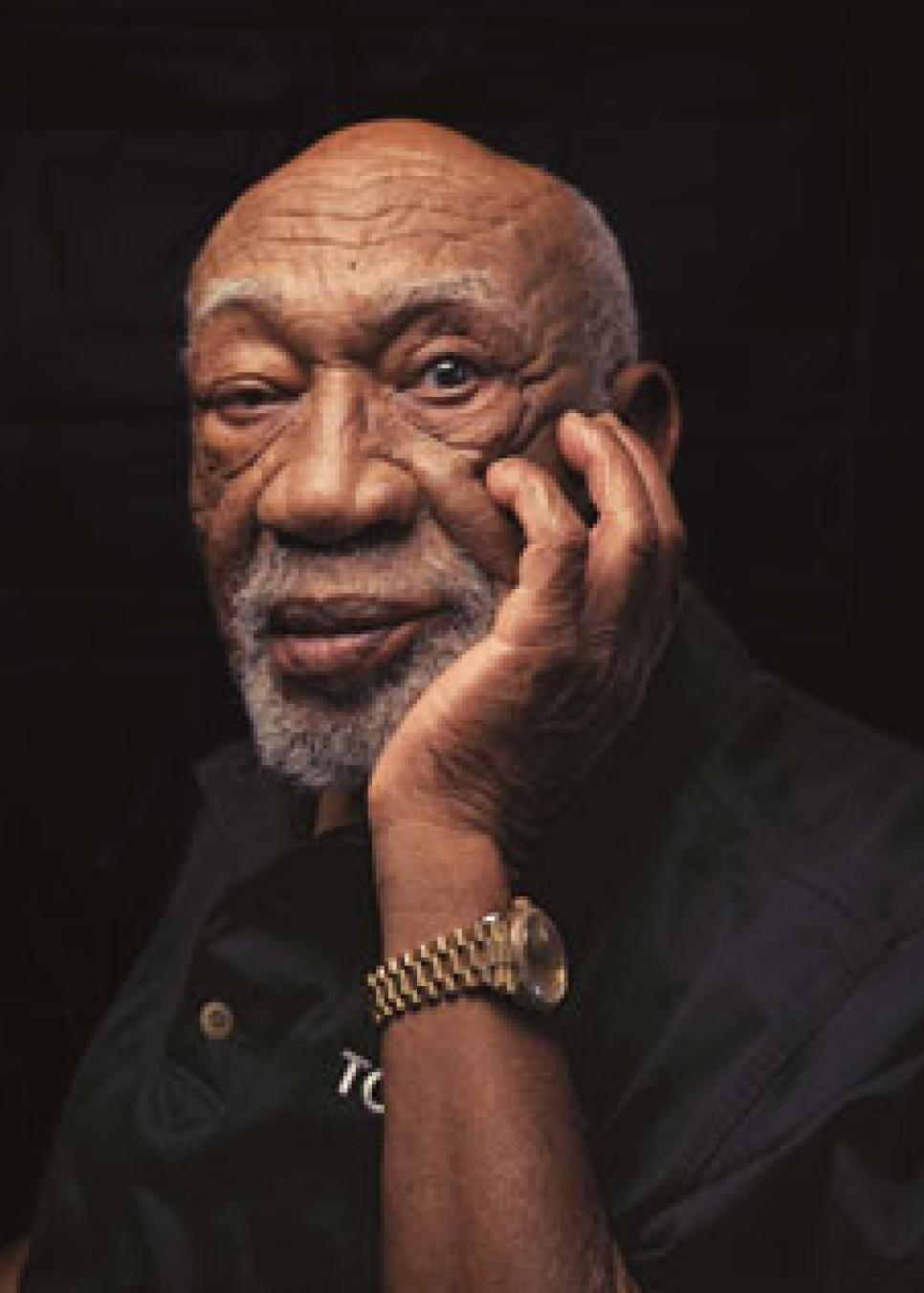

My Shot: Dr. Charlie Sifford

Editor’s note: In celebration of Golf Digest's 70th anniversary, we’re revisiting the best literature and journalism we’ve ever published. Catch up on earlier installments.

Charlie Sifford was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in November 2014; it’s pretty widely acknowledged Charlie was given very little else in life. Three months later, he died at age 92. As Jaime Diaz wrote in Golf World at the time: “Sifford was a gifted player, but not the most gifted African-American to come to golf in the mid-century. That distinction belonged to Teddy Rhodes. But Sifford, a native of Charlotte, N.C., had two essential qualities that allowed him to endure what others didn't. His extraordinary gumption kept him from becoming discouraged when tournaments shunned him and/or when galleries shouted racial taunts. And he had a passion for playing. In 1992, he told me for a story in The New York Times, ‘Nobody ever loved this game more than me.’”

Sifford took up the game as a 10-year-old caddie, was smoking cigars by 13, caddied for Clayton Heafner and in the 1940s became the personal pro and valet for the singer Billy Eckstine. Starting on the all-black United Golfers Association tour, he became the first African-American professional to beat a field of white pros in a PGA-sanctioned event in winning the 1957 Long Beach Open. “Because Sifford wasn't eligible for an ‘approved tournament players card’ until 1960, when the PGA of America finally dropped its ‘Caucasian-only’ clause, he didn't play what would become the PGA Tour regularly until he was 38,” Diaz wrote. “Though he managed to win the 1967 Greater Hartford Open and the 1969 Los Angeles Open, and played consistently enough to stay exempt by continuing to finish among the top 60 money-winners, Sifford never qualified or was invited to the Masters, an unrealized personal ambition that left him with hard feelings.”

Sifford’s curmudgeonly nature wasn’t given to him, either. He earned it from years of discrimination on tour. Earlier in this “Best of Golf Digest” series, PGA Tour pro Larry Mowry told the harrowing story of traveling by car through the Deep South with Charlie. The following My Shot with Senior Writer Guy Yocom appeared originally in December 2006. —Jerry Tarde

I knew what I was getting into when I chose golf. Hell, I knew I'd never get rich and famous. All the discrimination, the not being able to play where I deserved and wanted to play—in the end I didn't give a damn. I was made for a tough life, because I'm a tough man. And in the end I won; I got a lot of black people playing golf. That's good enough. If I had to do it over again, exactly the same way, I would.

I caddied a lot for Clayton Heafner, an outstanding player who twice finished second in the U.S. Open. I learned a lot just by watching him, and by the time I was 16, I felt I was good enough to take him on. Now, Heafner was a big man and had a temper, too—more than once he fired me on the front nine and rehired me on the back nine. I held my own against Heafner, but one day I made the mistake of playing him for $2, which was more money than I had in my pocket. When he closed me out and I told him I didn't have the $2, he picked me up and in front of all these people, carried me over to a water hazard, and threw me in. Splash! Talk about embarrassing—I never played for more money than I had in my pocket again.

The best black player who ever lived was Teddy Rhodes. I chased him for years beginning in 1947 and never could beat him when it mattered. There was so little money in the United Golfers Association tournaments, and to make anything you had to beat Teddy. And I couldn't do it. Finally Teddy got old. I won the Negro National Open five times in a row starting in 1952, and later won twice on the PGA Tour. But take the two of us in our primes, and Teddy was better. I saw them all, and I've always felt Teddy was as good as any of the best white players of his era, and that includes Sam Snead and Ben Hogan.

My first victory, in 1951, earned me $500. With guys like Teddy, Bill Spiller and Zeke Hartsfield to beat in the few tournaments there were, there's no way I could have made a living doing that alone. What saved me was going to work for Billy Eckstine, the singer and bandleader. Teddy and Joe Louis persuaded Mr. B—that's what we called Billy—to give me a job as his valet and personal golf instructor, and I did that for 10 years. I did whatever Mr. B needed doing, and he paid me $150 a week, plus all expenses on the road. I arranged his golf games, gave him lessons, took his clothes to the cleaners, anything. Not only did this keep me from starving, I had a great time. I saw all the best jazz musicians, met the greatest black athletes, traveled to lots of great cities, met lots of fascinating people.

Joe Louis was strong, but his strength didn't help him much in golf. Billy Eckstine had wonderful tempo and rhythm, but his musical ability didn't transfer to golf much, that I could see. The ability to play golf is unique, and it's not surprising that so many athletes who excel in other sports don't do all that well when they switch to golf. Their egos often get in the way, too.

I had a heart operation in July. Bad valve. I have to wear an oxygen tube all the time. You know what that means—no more cigars. I began smoking cigars at age 12 and kept right on. I loved them so much. But you know, I don't miss them that much. Knowing you can't have something takes away much of the desire to have it.

Stay away from greasy foods. Take a drink, but only once in a while, and stay away from whiskey completely. And get your rest. If you want to make it to 84 and survive a heart operation, you've got to get your sleep.

Golf is the game for a lifetime, but only if you learn to accept it for what it is. Earlier this year I could only hit my driver out there maybe 240 yards, and no part of my game was as good as it used to be. But the challenge never changes. Every shot is about executing the best you can, and when you succeed, you've succeeded, even if it doesn't compare to the way you used to do it. You can't be too greedy. Last April, not long before my heart operation, Joe Jimenez and I finished second in our division at the Legends of Golf tournament. I got a kick out of that. I executed well for an 83-year-old man.

__Tiger Woods is one of the few black players__who can putt the eyes out of the hole. Putting takes time to learn, and older black players like me couldn't hang out on the putting green for hours. Most of us were caddies and learned to play by sneaking out on the course when nobody was around. At the Carolina Golf Country Club in Charlotte, a bunch of us would sneak out there with a few clubs we'd borrow. We'd share them, hitting real fast, then running up to the ball and hitting it again. We didn't have time to putt, and except on Mondays when we were allowed to play the course, we rarely carried a putter with us. We'd use a 2-iron and get the putting over with.

I first saw Tiger when he was about 13. I knew he'd be good, but to be honest, the only one who knew he was going to be great was his daddy.

I saw more of Tiger as he grew, but I never found occasion to give him advice. What am I going to tell somebody who's that good, who doesn't have the problems I had? No advice I learned from my life applied to his. We talked, though. Tiger thanked me very sincerely. That meant a lot.

Most of the discrimination I experienced came when I got older. I grew up in a mixed neighborhood in Charlotte, and everybody was treated the same. Our next-door neighbors, the Wilsons, were white, and when their kids came over to play with us and got in trouble, my mom would whip them as if they were hers. And Mrs. Wilson gave me more than one whipping, too. I believed everybody was equal, and when I began finding out in my teens that not everybody thought that way, it made it that much harder to understand, let alone accept.

I don't smile much, and I never laugh. It's just something that's in me. If you'd been through what I've been through, you wouldn't be smiling, either. Walking around smiling all the time would have made no sense. It would indicate I approved of the way I was being treated, when I damn sure didn't approve.

Larry Mowry wrote a story for your magazine years ago [March 1988] about a drive we made together from Miami to Wilmington, N.C., on tour in the '60s. It was an eye-opener for him. We were in the Deep South during a time when black men and white men didn't ride together. I had a new Buick, and when we stopped for gas in south Georgia in the middle of the night and Larry went in to get some Cokes, a police officer took exception to me being in such a nice car. We got out of there, and 20 years later, Larry remembered what I told him when we crossed the county line: "If he knew this was my car, we'd both be buried in a cotton field and never heard from again."

When I was a kid, my dad, Shug Sifford, told me, "Be a man." That didn't sound like very specific advice, but when I got caught telling a lie, he'd say, "A man doesn't lie." When I'd slough off on my chores, he said, "A man works hard." Though he didn't say as much, being a real man means obeying your conscience and being honest with yourself.

I fought on Okinawa during World War II, and right after the war I was stationed in the Philippines. One day in Manila, a buddy and I came upon a horse-drawn taxi. I'd boxed a little growing up, and my buddy bet me $5 that I couldn't knock the horse down with one punch. I hauled off and belted that horse between the eyes, and he did go down. The Filipinos who saw it beat the living hell out of us. I came out of that a lot worse off than the horse, I'll tell you that.

I once made two holes-in-one in the same competitive round at Seattle. Another time, at a tournament for local pros in Ohio, I made an ace and won the use of a Chevy for a year. In 1986, at the Johnny Mathis tournament, I came to a tee, and sitting right there was a new Buick. I knocked a 5-iron into the cup and thought I'd not only won the Buick but $100,000. But the people who sponsored the thing claimed the prize had been withdrawn, and the sign on the tee was partially torn by the time I got there. I ended up getting the car, but I had to sue to get the $100,000. I've made eight holes-in-one in my life, and all of them were in competition.

In June of this year I was given an honorary doctorate by the University of St. Andrews. It was the first time I ever went to Scotland, the first time I could afford to go, really. And I played the Old Course at St. Andrews. It was different than what I saw on TV all those years, that's for sure. Don't ask me what I shot. I didn't keep score.

I played in the U.S. Open 10 or 12 times but never played well. None of the black players back then did. We had to qualify, and getting there was a rare opportunity, your one chance. We weren't used to the courses or the atmosphere. It's hard to explain, and even harder to understand, so we'll just leave it at that.

The Masters didn't want blacks in general and didn't want me specifically. When I got on the PGA Tour, the one thing I was certain of was that I would never get invited to Augusta no matter what I did. In 1962 I shot a 67 in the second round of the Canadian Open to take the lead, and the club immediately got a phone call. The next day there was an announcement: "The Masters will not offer an automatic invitation to the winner." I don't regret not being invited to play in the Masters, I've never been to one, and all the money in the world couldn't get me down there. Because I don't want to be anywhere I'm not wanted.

The United Golfers Association had a secretary, a president and so on who went around organizing the tournaments. We had sponsors and prize money. Not much; $10,000 was a big purse. We played in Detroit, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Cleveland, Washington D.C. and then the Negro National Open, which was played at different public courses. The interesting thing was, we didn't discriminate. White people played in our events, too.

No matter how much money you make, you've got to save something. Even when I was making $150 a week traveling with Billy Eckstine and sending much of it home, I always put something away. It's better to have your own than to borrow.

Here's a secret to winning money: Keep the double bogeys off your scorecard. Always hit your ball in a place where you can't make a double bogey. I don't care what kind of golfer you are, there's almost always a place to hit your ball where you can avoid a double bogey. You can survive some bogeys, but those doubles will drive you broke.

I've done everything I wanted to do, except play a little more golf. Soon as I recuperate from my heart operation, I'll be back on the course. I'll break 80, too, and when I better my age it'll be the only time I won't regret being 84 years old.

.jpg)