News

Worlds Apart

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the U.S. Open's lone appearance in my hometown of Buffalo, NY. To be clear, I haven't lived there for a while, and as a child, I never stepped foot on the course where it was held. Yet anyone who has lived through a "Wide Right", a "No Goal", and a "Music City Miracle" will be quick to take pride in the fact that for one weekend a century ago, a flat plot of old cow pasture that lies on the city's northeast edge played host to America's preeminent golf tournament.

The USGA's decision to host the 18th U.S. Open at the Country Club of Buffalo was far less surprising than it might seem today. Only a decade earlier, the Country Club was moved to make room for the Pan-Am Exposition World's Fair (where president McKinley was assassinated), and as the nation's largest inland port and eighth-largest city at the turn of the 20th century, Buffalo was as important to the country's landscape as any other major city. It didn't hurt to have a well-connected Buffalo businessman who was also a high-ranking USGA official in your corner; Ganson Depew, son of U.S. Senator Chauncey Depew, was the tournament chairman.

The story of the tournament's results is well documented: John J. McDermott, the first American and youngest champion ever, won his second consecutive Open with a 2-under 294. The course played at par 74, including the first and only par 6 to ever appear in U.S. Open play -- McDermott would play the 606-yard 10th at a whopping 6-under -- both indicative of one the longest courses of its time. At 6,326 yards, it was the third-longest Open to date, with a field scoring average of 80.72. McDermott was one of only 16 players to break par -- a true U.S Open course for certain.

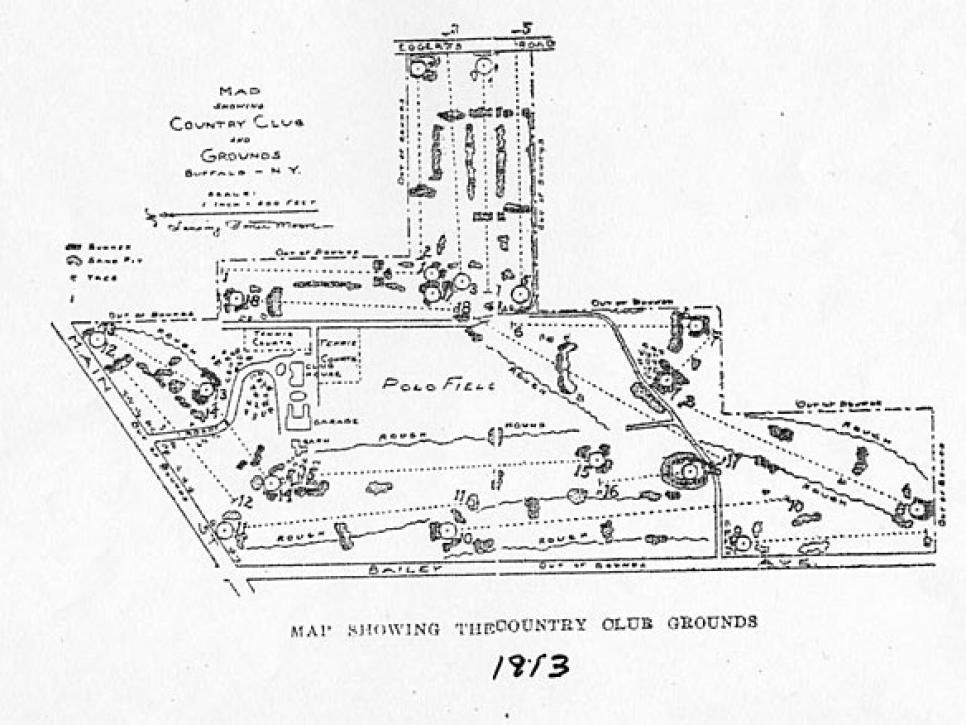

A drawing of the original Country Club of Buffalo layout as designed by Walter Travis.

The 1912 Open also featured an important generational passing. Inaugural 1895 champion Horace Rawlins would make his last tournament appearance (missing the cut), while an amateur Walter Hagen, who came to Buffalo as the Assistant Pro of the Country Club of Rochester, made his first. Hagen would only play a practice round that year, officially making his debut in the tournament in 1913 at Brookline.

But what happened to the Country Club of Buffalo after the 1912 U.S. Open is far-less documented. Following a path that parallels the city's great demise -- one that mirrors the country's waning dependence on manufacturing and subsequent suburban sprawl -- the CCB, too, picked up and moved to the outlying towns, settling five miles away in Williamsville, NY. Opened in 1926 and designed by legendary architect Donald Ross (who also helped redesign the original CC course), to this day the Country Club of Buffalo is a respectable symbol of early 20th century golf architecture.

In it's wake lies Grover Cleveland Golf Course.

In 1925, the CC of Buffalo sold the course to the city, which would rename it after the former Buffalo Mayor and United States President. It would continue as a quality golf course for 22 more years until, in 1947, the course was shortened to 5,621 yards (from the back tees) to accommodate the building of the Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Eliminating an entire three-hole chunk of the original course, the hospital forced an overhaul of the layout, and in turn, erasing most of the Open history with it.

In a post-World War II America, no one questioned the city for eliminating portions of a government-owned golf course to build a veterans hospital. The hospital also represented a shift in American thinking -- the industrial revolution had brought the concepts of fast and efficient to the forefront of our culture. Despite being a city that features over 80 historical landmarks, with buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, Henry Hobson Richardson, Louis Sullivan, and just about every other prominent architect of the 19th and early 20th century, 1947 Buffalo had no qualms erasing an important part of its sporting history for the less-than-striking medical center that now looms over the course.

The view from the 5th hole looking back at the veterans hospital.

The timing of the Veterans hospital also coincided with Buffalo's peak population. 1950 signified the city at its largest, which also meant the beginning of its decline. Industrial production -- specifically the steel industry of the Great Lakes region -- was sent overseas, and with it, many of the jobs that populated the city. Ironically, today the hospital could be built just about anywhere within the city limits, as the loss of manufacturing jobs and rapid suburbanization has not only resulted in a decline in population, but building vacancies that have reached epidemic levels. As the city's economy dwindled to that of one of the poorest in the U.S., with a population over 250,000, golf became a distant afterthought.

Now playing at par 69 with a rating of 65.5, the course played no role in my golf game growing up. Raised roughly 20 miles away, my earliest cognizant memories of Grover Cleveland GC are of visiting my ailing grandfather in the adjacent hospital, and later, my college years -- it sits across the street from the University of Buffalo's South Campus, where lived as a student. In fact, my first time stepping onto the fairways was for a drunken stroll with a girl I was dating, which was still a far cry from some of the vice-laden adventures others from my school had experienced on the course. To this day I still look for cheese-whiz in the cups. It wasn't until I left Buffalo that I started to become more familiar with the former Open course and its history.

After I graduated and moved to Brooklyn, my parents relocated to about one mile north of Grover Cleveland GC, making it an easy place to play a quick nine (or however many holes you could get in before sundown). It's the type of place you can play a round for about $25 -- with a cart (try saying that about any other U.S. Open course); the type of place you never have to worry about getting a tee-time (just don't expect a quick round). It's also become the place where my father and I have played many rounds together. It might not be as challenging as the other courses we play, but my dad's shaved about five strokes from his game because of the ease and ability to play it frequently (me, not so much). And it never hurts to be able to brag about breaking 80 on a Donald Ross-designed U.S. Open course.

As many are quick to point out, the course bears little resemblance to the U.S. Open layout. Just as Buffalo doesn't resemble the great city it once was. But what it lacks economically, it more than makes up for as a place to nourish and develop talent. Now a college city, Buffalo has fiscally aligned itself with the many universities that dot the city's landscape. With nearly 40% of the population 24 years old or younger, higher education facilities are the number one employer in the region. This in turn has led to a dedicated focus on supporting youth sports programs, which has returned a high yield of professional and Olympic-caliber athletes.

And golf -- specifically Grover Cleveland -- also holds a special place among Buffalo's athletic community. Aside from hosting events like the Western New York PGA-sanctioned Erie County Amateur Championship

, it has become an important municipal course in the development of young golfers. And because of its location, and programs such as Clubs for Kids

, increasingly important for those from the inner city. The region itself boasts no less than 13 municipal courses within a 20-mile radius of downtown Buffalo.

All the more reason the pride most Buffalonians now exude stems from, notably, their sports teams, as well as the blue-collar work ethic every citizen must exhibit to thrive; a perfect metaphor for the remnants of a historic Country Club -- the tennis courts remain, but the polo fields are long gone. You won't see too many professionals walking these fairways anymore, but it is a reminder of the prestige that once embodied a city. That for one weekend, 100 years ago, the entire golf world was focused on a flat plot of old cow pasture on Buffalo's northeast edge.

A view of the 17th green; one of the originals from the 1912 Open, which was later redesigned by Donald Ross.