News

A Week Like No Other

The most popular salutation from the homegrown New York galleries at the 2002 U.S. Open at Bethpage State Park was a declaration articulated in a question. "Hey (insert accomplished tour player name here), how do you like our (insert colorful adjective here) municipal golf course?"

The 102nd U.S. Open at Bethpage Black in Farmingdale, N.Y., was a groundbreaking occasion in major championship golf, most notably because it was "The People's Open." In a nod toward celebrating an overlooked slice of the game's rich history while repudiating its own myopia, the USGA for the first time conducted its biggest tournament on a truly public layout. The Black had long been a red-eye favorite among New Yorkers, who for a chance to access the A.W. Tillinghast gem were compelled to slumber in their cars. The blue bloods were the interlopers on this occasion.

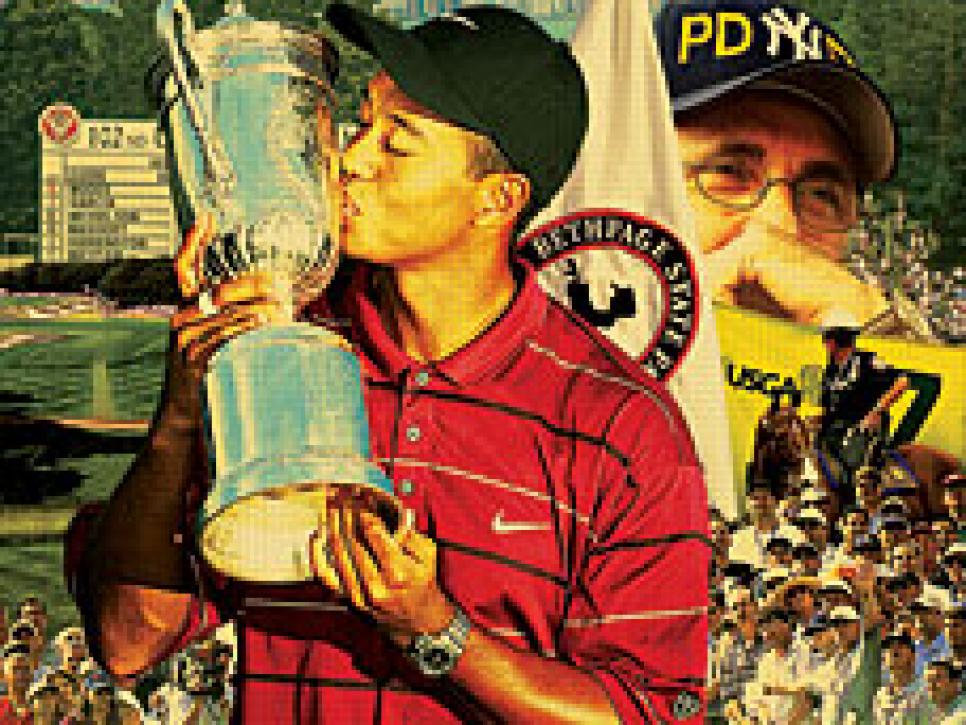

With a mix of populism and parochialism, Bethpage wasn't for the meek of heart or the misguided of stroke. That Tiger Woods emerged with his second Open title was hardly a surprise; it was the seventh triumph in 11 major starts for the world's No. 1 player, who just so happened to be a product of public golf.

When the Open returns to Bethpage Black, the 156 competitors will find the big layout, tweaked by Open Doctor II, Rees Jones, larger and more exacting than when Woods was the only player to break par in outdueling Phil Mickelson and Sergio Garcia. But it's doubtful that this 109th playing of the national championship will be more meaningful than the spectacle of seven years earlier, played in the shadow of the Big Apple and earth-shattering tragedy.

Fate put that U.S. Open in New York less than one year after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. The championship's success is what brings it back. But, ironically, a return to Bethpage again represents a respite from collective angst, this time over an economic tsunami that has waylaid Wall Street and Main Street.

"It was such a hard golf course, but even as wrapped up as you had to be in your game, it was hard to not notice the atmosphere and how much that tournament meant to people," Scott Verplank recalls. "I don't know if you can say, 'Here we go again,' but there are certainly serious things going on that worry everyone."

Indeed, it is hard to compare current events to the horrors of the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, not to mention the anthrax scare soon after that exacerbated the nation's sense of vulnerability. Bethpage helped lift a collective moroseness.

"We were not too far removed from 9/11, and I think the whole city was looking for something to wrap their arms around, anything, any sporting event, anything to take themselves out of that moment in time. The U.S. Open was that event," says Woods, whose three-under-par 277 was three better than Mickelson. "I played well and ended up winning the golf tournament, but I think the overwhelming memory of the whole event was just the week in general. I can't believe how many thank-yous we got as players: Thank you for coming out and supporting New York. We didn't do anything. We just came out and played. But to them, they wanted a distraction from what they witnessed and what they were dealing with and all of the people they had lost in their lives."

Adds Mike Davis, senior director of rules and competitions for the USGA, "I think the people of New York were so ready for that championship because at that juncture, not even a year after 9/11, they were looking to have something to talk about and get excited about. It will be interesting to see in this go-around how different things will be."

Although the championship was successful, it wasn't a complete escape. Altered reality intruded.

"Security at the U.S. Open changed forever with Bethpage," Davis says. "The authorities believed they had to do some extra special things or the tournament itself could be a target. They had reason to believe that security needed to be elevated. We had the FBI, CIA and Secret Service weighing in. There were things they didn't even tell us, but that they were suspicious about. For us, that was significant to altering our view of running the championship."

Davis, who in 2006 assumed from Tom Meeks the responsibility for setting up Open golf courses, has made his own alterations to the championship, though the tournament remains a strategic exam on a stout layout.

"The U.S. Open is always like taking a quiz without reading the textbooks," Steve Flesch says.

If that's the case, then competing at Bethpage Black in '02 was like taking the bar exam after attending shop class. Not only was Bethpage a public course with which few were intimately familiar, but also it was a public course as juiced as Manny Ramirez. At 7,214 yards, the Black was the longest venue in Open history to date. Two par 4s, the 10th and 12th, were the longest ever at 492 and 499 yards, respectively. Stimpmeter readings on the subtly sloping greens approached a frightful 15. And heaven help those who strayed into the four-to-five-inch fescue rough. The penalty was often a full stroke and closer proximity to gallery denizens unrestrained by such considerations as decorum or decibel levels.

"Above all, Bethpage is a marvelous golf course," says Nick Faldo, who endeared himself to the locals by wearing an "I New York" hat and who thrust himself into contention with a tournament-low 66 in the third round that propelled him to T-5. "There was that beautiful bunkering and the movement with the holes going down then up to elevated greens. The old style of it was simply brilliant, but there could have been more imagination to the setup, not just straight lines of high rough. It was pretty static."

While the stringent setup flummoxed many, few were troubled by the gallery's New York state of malign.

"I never got heckled, but there were tons of comments. Tons. And, you know, they were creative," recalls Stewart Cink.

"I swear we played in winter," says Jim Furyk, who missed the cut the year before he claimed his own Open title in '03, of his first memories of Bethpage. "It was a great course, but a bad setup. It was long and hard, and it beat me up, and a few people let me know about it, telling me I sucked—and I did. I didn't particularly want to hear about it at the time, but they were on to me."

"I liked the course. I liked the test. I liked the noise," remembers Ireland's Padraig Harrington, the two-time reigning British Open champion, who tied for eighth and whose 68 was one of only four rounds under par on Black Friday, when chilling rains that seemed to have blown in from the British Isles sent scores and tempers soaring. "Everyone likes to play in a great atmosphere, and that was a great atmosphere. I loved that crowd. They were mostly Irish anyway."

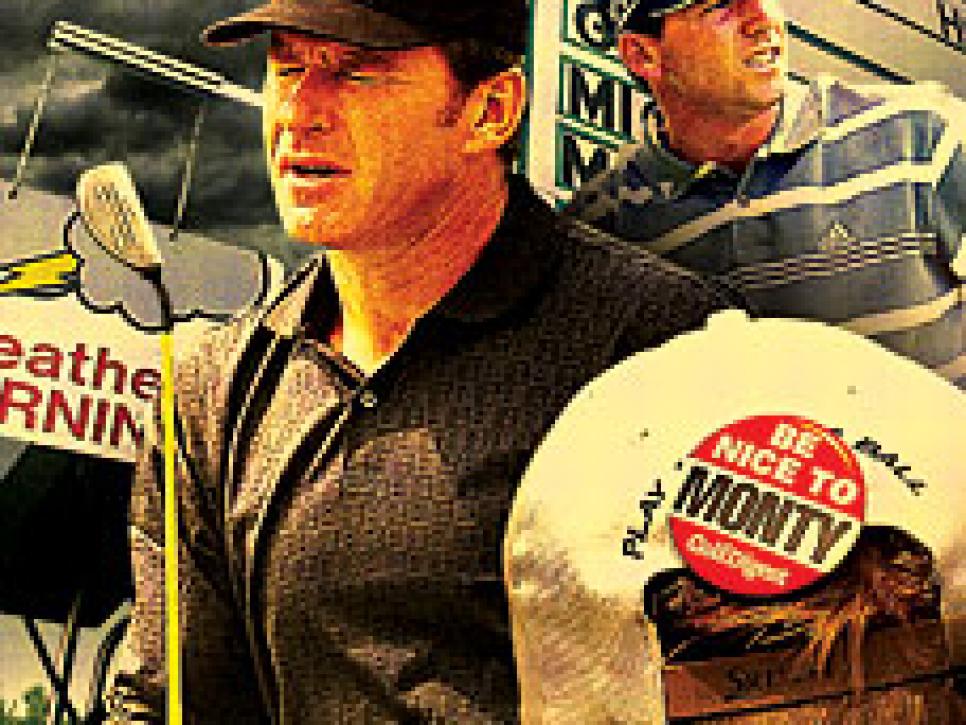

Harrington notwithstanding, many of the 42,500 in attendance each day saved their sharpest barbs for Europeans. Two easy targets were Garcia and Colin Montgomerie. The latter had the good sense to miss his first Open cut in 10 years, but not without absorbing several scatological critiques about his anatomy. (To be fair, the object of Golf Digest's "Be Nice To Monty" campaign was, all in all, treated well by spectators that week.) The former had the temerity to not only contend for his first major title, but also to do so while fighting grip yips—incessantly "milking" the club before every shot—and lamenting perceived preferential treatment by the USGA for a certain player who happened to be the best in the world.

When fans weren't heckling him, they were counting the number of times he would grip and regrip … and regrip.

Ask Garcia about his memories of that week, and he'll gladly supply an opinion—the surprise being that it's fit for print. "It was a good week, and a hard week, and I had a chance to win," says Garcia, who finished fourth after closing with a 74. "As far as the rest of it, if that didn't make you tougher, then nothing would. It was a good experience. Not necessarily a fun thing, but, still, I learned a lot about myself."

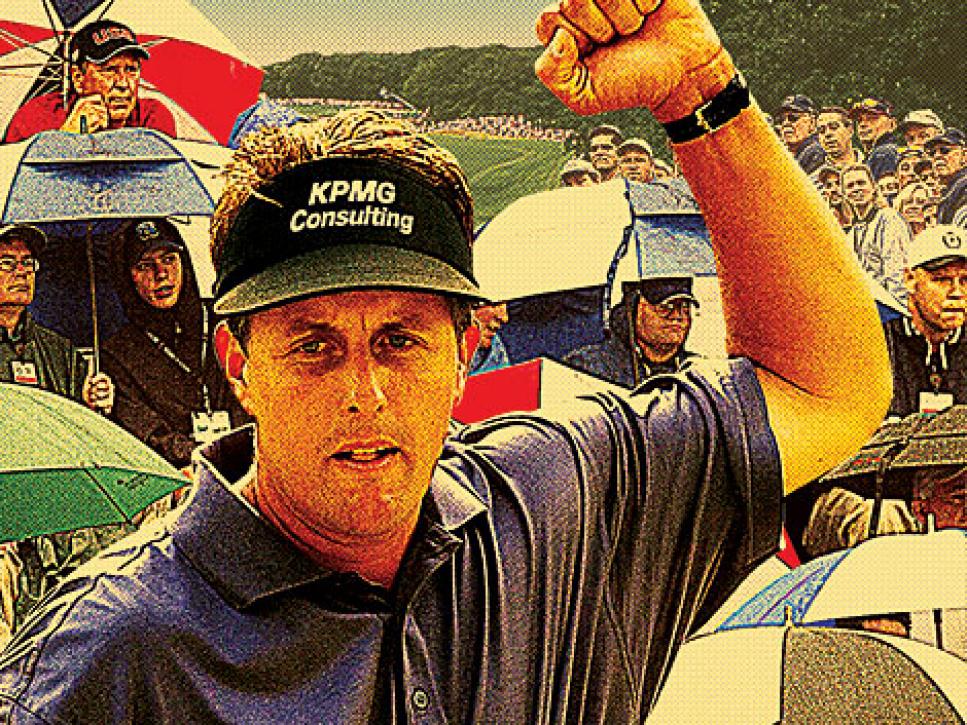

The old grounds were electric Saturday afternoon as Garcia and Mickelson made late charges and posted 67s, gaining three on Woods, who still led by four over El Niño. That set up a Sunday showdown in scene-setter conditions reserved for cinema. Woods, who won easily despite a closing 72, and Garcia comprised the final group while Mickelson embarked in the penultimate twosome with Jeff Maggert, but not before the galleries serenaded him with a verse of "Happy Birthday" as Lefty celebrated his 32nd that very day.

"The atmosphere was unbelievable all week," says Jim (Bones) Mackay, Mickelson's caddie. "I remember we were on the 15th green putting out on Sunday and the walk to the 16th tee was almost 300 yards, but we could hear the fans on 16 chanting, 'Let's go Mickelson!' It was like that all around the golf course, and, yeah, they were pulling for Phil, but the fans got really into it with all of the players. They were fired up."

"That was the first Open where we didn't visit the typical U.S. Open course from the usual rotation, and it was nice," says Dudley Hart, who that week became the answer to a trivia question. With the USGA switching to a two-tee start that year to accommodate the slowing pace of play, Hart became the first man to begin the championship on the 10th tee. "Everybody out there, probably everybody from New York, felt the course belonged to them, and they were proud of that, and they let you know it."

Whether similar circumstances can emerge this time depends on the weather and on the lighter touch of Davis, who is a curious figure in golf circles. He is viewed more favorably than his predecessor even as winning scores have gravitated upward. Perhaps it is because his risk-and-reward features, particularly graduated rough, allow players to exhibit their skills or fall on their swords.

But, of course, this U.S. Open is likely to be just as well received as the last. While portions of the 7,426-yard golf course are certain to be disagreeable to the entrants—because that is part of a player's DNA—the intrinsic worth of the Tillinghast gem won't go unappreciated. The New York fans will be out in force, energetic and effusive. Woods is defending his Open title, the one he miraculously captured on one leg at Torrey Pines.

"You can't go back and re-create that particular atmosphere, given the events at the time. And you can only have those firsts once," notes Davis. "That being said, I think it's going to be a fantastic championship because the golf course is even better and because of the fans. I imagine it will be a happening."

"The people that were there [in 2002], you definitely felt like they were taking an ownership position with that golf course and the tournament," says Cink. "It really was the 'People's Open.' I think it probably will be again. I don't see that changing. I think it has the chance to be just as memorable and something you're going to be glad to say that you were a part of."

You better (insert colorful adjective here) believe it.