News

The Great Survivor

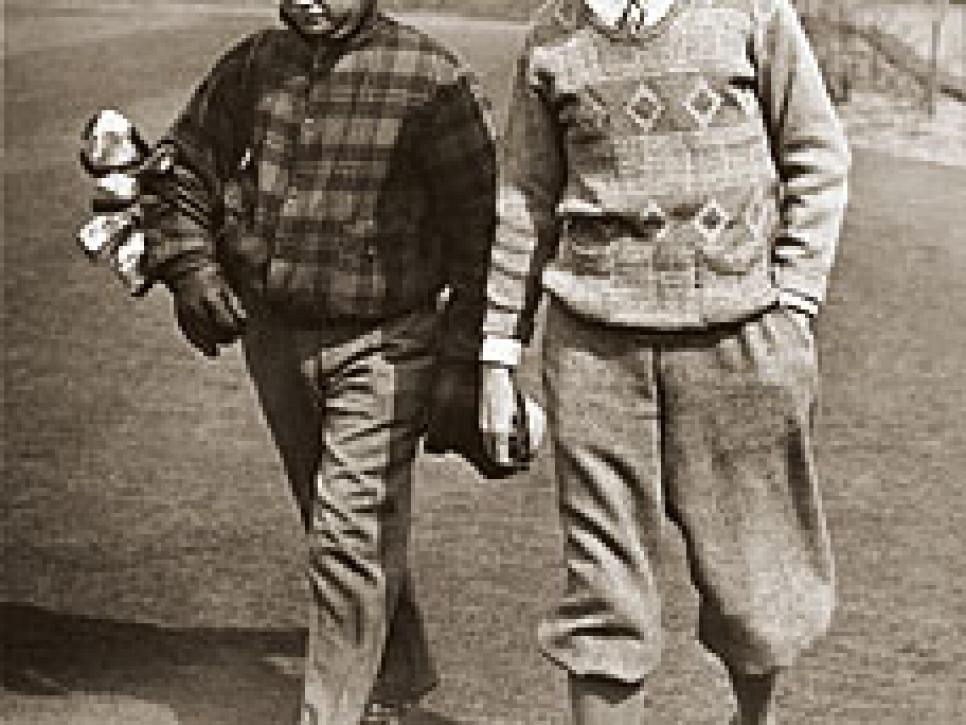

hEADY TIMES: A young man of privilege who learned the game on his father's estate, Travers won the 1915 U.S. Open at Baltusrol (above) after taking four U.S. Amateur titles.

Peering into the scrubby woods bordering the fourth hole at Baltusrol GC's Upper Course, one can discern the remains of an old elevated tee. On June 18, 1915, Jerry Travers scaled this modest ledge with a chance to win the U.S. Open. Leading after three rounds, the nation's most accomplished amateur stood on Baltusrol's old 10th tee in the last round, figuring a back-nine 39 would give him the title.

Although a dominant match player, Travers had never contended in the Open because of a prominent Achilles' heel: erratic driving. Consequently, he eyed Baltusrol's treacherous "island hole"—a drive-and-pitch test to a green surrounded by a moat—wielding a driving iron.

Seeking control, Travers sliced his tee shot out-of- bounds. After he re-teed, his second effort dove left into tall grass 175 yards from the hole. Lying two in the deep stuff—the out-of-bounds penalty in 1915 was distance only —his title prospects looked grim.

But Travers wasn't a player to be counted out. Apt to deflate match-play opponents with miraculous recoveries, Travers pulled out his jigger and launched a high-arcing salvo that cleared the moat before settling a yard from the flagstick. After making a 4, Travers birdied the 15th, posted a back-nine 37 and won the championship by a stroke. He later called his third shot at 10 "the greatest I have ever made in all my golfing career."

As a boy, Travers swatted gutta perchas on the back lawn of his father's sprawling estate in Oyster Bay, N.Y., a wealthy enclave on Long Island's Gold Coast not far from the land that would become Bethpage Black. Before Francis Ouimet won the 1913 Open, Travers won four U.S. Amateurs; inspired by Ouimet's victory, he became the second amateur to win the U.S. Open.

After his crowning triumph Travers abandoned national competition for a budding Wall Street career. But after prospering in the 1920s, he met misfortune following the 1929 stock-market crash. During the Great Depression, middle-aged Travers turned pro but couldn't earn a living; his family bounced from New Jersey to Manhattan to a modest Connecticut farm, worlds away from tony Oyster Bay. Although he later regained respectability, Travers died having suffered terribly in the wake of our nation's greatest economic calamity.

Jerome Dunstan Travers was born in New York on May 19, 1887. His father, Vincent Paul Travers, was president of Standard Rope and Twine Co. and treasurer of Travers Brothers Co., a maker of cordage products. Owner of an Oyster Bay estate, Vincent knew Theodore Roosevelt, whose nearby Sagamore Hill estate would serve as the summer White House during his 1901-09 presidency. With his wife, Catherine, Vincent had five children; born on the feast of St. Dunstan, Jerry was the youngest of three Travers sons.

Jerry's back-lawn experimentation started in 1896 after one of his brothers gave him a mid-iron and some gutties. For the next three summers he played incessantly on a makeshift three-hole course he devised on the estate's front lawn. As a teen he honed his skills at Oyster Bay GC and later at Nassau CC, where he was taught by Alex Smith, the club's Scottish professional who later won two U.S. Opens.

In 1904 Travers was just 17 when he upset reigning British Amateur champion Walter J. Travis at the Nassau Invitational. Travers and Travis, a 42-year-old Australian immigrant dubbed "The Old Man," would trade victories for the next decade in what would become American golf's first great rivalry. Travers won the U.S. Amateur in 1907, 1908, 1912 and 1913, twice defeating Travis en route to winning. He captured five Metropolitan Amateurs, four New Jersey Amateurs and several other titles, establishing himself as the country's top amateur.

Standing 5-foot-7 and weighing 135 pounds, Travers held his woods with a baseball grip, his thumbs positioned between his index and middle fingers. When playing irons, he repositioned his right thumb so that its nail dug into the top of the shaft. Despite his driving troubles, he was precise with his irons and deadly with his center-shafted Schenectady putter.

Though hardly imposing, Travers dispensed opponents with poker-faced efficiency. "Travers was the greatest competitor I have ever known," said Smith, his teacher. "I could always tell just from looking at a golfer whether he was winning or losing, but I never knew how Travers stood."

While compiling the greatest amateur record preceding that of Bobby Jones, Travers briefly lost his way. He didn't win a tournament in 1909, won only once in 1910 and skipped the U.S. Amateur both years. Moreover, he was disqualified for missing his final-day tee time at the 1909 U.S. Open and didn't show for his semifinal match at the 1910 Apawamis Invitational.

Whether Travers' aimlessness stemmed from swing problems, immaturity or fast living has long been a topic of speculation. In The Story of American Golf, Herbert Warren Wind writes that Travers returned to competition in 1911 "having learned during his two lean years that a young man cannot be both a professional playboy and an amateur golf champion."

In an interview last month, Travers' 83-year-old son, David B. V. Travers, recalled hearing about his father imbibing with Scottish comedian Harry Lauder and running with rakish New York politician Jimmy Walker. But he claims his father's carousing ended with his marriage to Geraldine Hohman in 1921. "My mother wouldn't marry him until he swore off drinking," says David, a Yale-trained architect who lives in Milford, Conn.

Educated in Manhattan boarding schools, Jerry Travers had no interest in his father's rope-making concern. "They tried to introduce him into the manufacturing," David says. "He said, 'I was afraid my hands would get caught in the machine.' "

In December 1914, The New York Times reported that a seat on the New York Cotton Exchange was bought on behalf of Travers, who had been connected for several years with the Baruch Brothers brokerage firm. According to David, noted financier Bernard Baruch and two other investors staked Travers to his start on Wall Street. "[My father] said, 'How can I earn money for my family?' " David says. "And then [Baruch] very unflatteringly said, 'Jerry, anybody can make money on the cotton exchange.' "

After winning the Open—he remains one of only five amateurs to have done so—Travers stopped competing nationally to nurture his business career. He married Dorris Tiffany of Newburgh, N.Y., in October 1916; two weeks later, 68-year-old Vincent Travers died. Two years later, tragedy struck Travers again when Dorris died at 29. According to David, Travers' first wife perished in the influenza pandemic that killed millions worldwide.

By 1920, Travers lived in the Montclair, N.J., household of his sister, Gertrude, and her husband, Samuel Neidlinger, according to federal census records. And in November 1921 he married Hohman, a college-educated Internal Revenue Service clerk from Montclair.

The Roaring Twenties were a heady time for Travers. Geraldine gave birth to a son, Jerome, in 1922; a daughter, Geraldine Anne, in 1924; and David in 1926. The family lived in Montclair while Travers worked on Wall Street and kept an apartment on Manhattan's fashionable Riverside Drive. An Upper Montclair CC member, he won the club championship in 1923.

But Travers' life changed drastically after the 1929 stock-market crash. With the nation hurtling into the Depression in October 1931, he sold his seat on the cotton exchange. Then, in April 1932, 44-year-old Travers announced his intention to become "a businessman golfer" and resigned as president of the New Jersey State Golf Association. The decision to turn pro pained Travers, his son says. "My father had the reverse mores of today," he says. "A good golfer never played for money."

During the Depression, Travers played exhibitions and launched various golf-business ventures but made little money. His son remembers a milk company calling Geraldine relentlessly about unpaid bills and Jerry's distress over not being able to pay a butcher. In the late 1930s, after losing their Montclair home to foreclosure, the family moved into a third-floor apartment near Columbia University in New York City.

"That's when my father would come home [after] having to borrow money to buy food for us," David says. "I'm sure he felt so inadequate. … I'd ask him for car fare to go to the World's Fair [in 1939], and he'd give me his last 50 cents."

In 1940 the Travers family moved to Meriden, Conn. "My mother, God bless her, found this farm for $7,500," David says. "Somehow she got my dad's friends to loan them the $7,500 and bought it."

While in New York, Jerry and Geraldine had sent their older son to a Kansas agricultural school in anticipation of the move, David says. And soon after arriving in Meriden, 15-year-old David found work delivering milk for nine cents an hour. "I would go to work at 2:30 in the morning, and my father would get up and make me oatmeal," he says.

The Travers farm was near the nine-hole Pleasant View GC, where in 1941 Jerry gave an exhibition on opening day. According to David, the former U.S. Open champion helped out at the course and aspired to open a driving range on the family's property.

But after America entered World War II later that year, Pratt Whitney Aircraft Co. hired Travers as an inspector at its East Hartford, Conn., plant. After a decade living hand-to-mouth, Travers was earning a regular paycheck. But the Depression had taken a toll on him. "He was a breadwinner at last, after all those years of, I think, being clinically depressed," David says.

Still, Travers couldn't escape heartache. During the war, Geraldine began treatment for mental illness; she would spend the next 18 years in the Connecticut State Hospital in Middletown, says David, who attributes his mother's health problems to the stress she endured trying to create a stable life for the family. Later in the decade, Geraldine Anne Travers—who worked as a draftsman for Pratt Whitney and subsequently for a New York engineering firm—also began treatment for mental illness at Central Islip (N.Y.) State Hospital, where she remained for 13 years, David says.

During his daughter's hospitalization, Travers regularly traveled by train from Hartford to visit her, David says. "He was an unsung hero in terms of family care and responsibility," he says. "He did what he could, even though he felt helpless."

With other commitments taking precedence, Travers played little golf during the 1940s. Late in the decade, however, he invited his old New Jersey pal Alexander (Sandy) Calder to Meriden for a round at Pleasant View. A playing partner of Travers' at Upper Montclair in the 1920s, Calder drove up with his son Fred.

Fred Calder, 84, remembers the outing. "Travers had played the day before for the first time in five years, and he said, 'I had a hole-in-one getting ready for you guys,' " Calder says with a laugh.

Calder was unimpressed with Travers' ball-striking but captivated by his putting stroke. "The minute he stroked a putt, I knew he was a great putter," he says. Needling Sandy Calder for his wayward driving, Travers also projected a feisty air, Calder recalls. "He was a cocky little fella," he says. "I could see that he must have been a hell of a competitor."

On March 29, 1951, Jerry Travers died at 63 in East Hartford, where he had moved two years earlier. A long-time smoker, he succumbed to a heart attack after a coughing fit, David says. A 13-paragraph New York Times obituary recounted Travers' golf championships without mentioning his later struggles, while a three-paragraph funeral announcement in the Meriden Journal identified him simply as "one of the country's greatest golfers."

Having confronted adversity that dwarfed his lie in the deep rough at Baltusrol, Travers was buried on a gentle slope near the back of Sacred Heart Cemetery in Meriden. But despite his trials, Travers never complained, David says. "Life threw plenty at him," he says. "He had the integrity not to crack and not to be overwhelmed by humiliation."