News

The Waiting Game

The date of capitulation was June 13, 2002. THAT'S when the purists at the USGA had to submit to the reality that 15 sunlit hours per day in mid-June in North America were insufficient for accommodating 156 of the world's finest golfers competing in the national championship.

Until then, every U.S. Open participant had begun his round on the first hole. For 101 years, no matter the time zone or the golf course, 15 hours provided enough daylight, barring weather delays, for an entire field, playing in threesomes, to tee off on No. 1 and hole out on No. 18. But in 2002, at Bethpage State Park's Black Course in Farmingdale, N.Y., the USGA opted for a two-tee start for the opening two rounds. One year earlier, at Atlanta Athletic Club, the PGA of America had abandoned a one-tee system in its PGA Championship.

"The last two or three groups were finishing, almost literally, in the dark the last couple of years, which we felt was unfair," says Tom Meeks, then senior director of rules and competitions for the USGA. "They had been using the two-tee start on the PGA Tour for years. Guys were used to it. It filled up the golf course faster and saved us about two hours, and we had some wiggle room if there was bad weather."

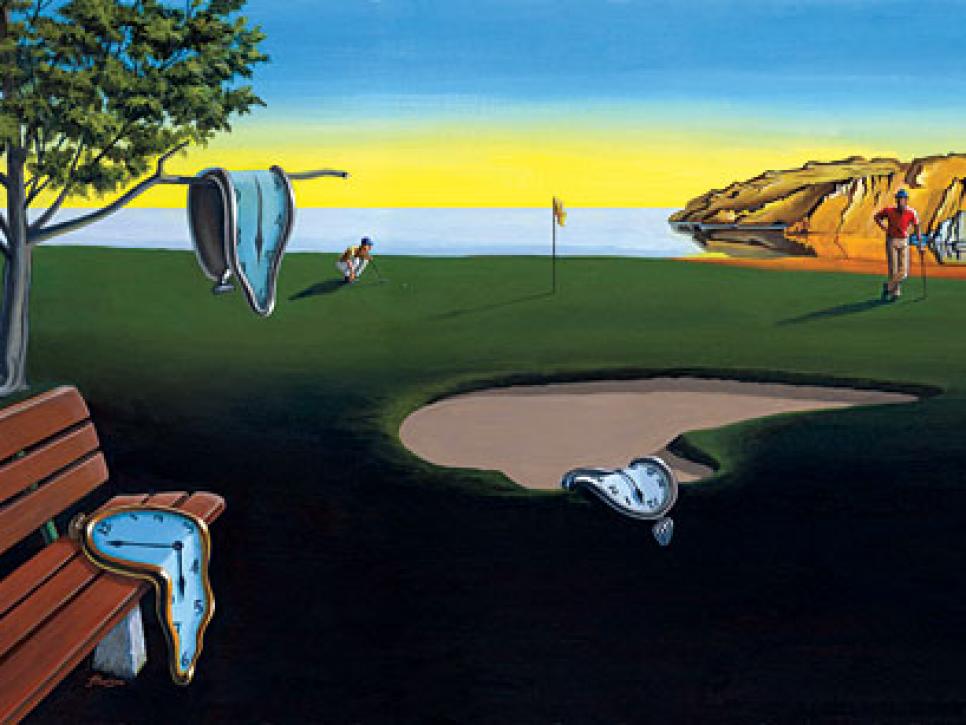

Left unsaid but implicit was the fact that the competitors' methodical pace had become, for lack of a better term, a bogeyman, casting a pall over the competitive landscape at the game's highest level. And there it remains. As the 108th U.S. Open at Torrey Pines GC's South Course in La Jolla, Calif., approaches, dialogue on the subject proliferates yet the problem persists.

"Pace of play has always been a problem; moreso in the eyes of some than others," says PGA Tour commissioner Tim Finchem. "At the professional level, it has always been a challenge to maintain a system that's fair to the competitors and tries to maintain etiquette in the game. You owe your fellow competitor the courtesy of maintaining a reasonable pace. … It has come to a point where we are going to have to really analyze all of it and ask ourselves: Is there a better way to do it, whether it relates to a slow player, whether it relates to the setup of the golf course, whether it relates to field sizes and the rest, and we are committed to doing that."

At the behest of Peter Dawson, executive director of the RA, the topic of slow play was added to the agenda at the World Golf Foundation meeting in Ponte Vedra Beach, Fla., following the Players. "It certainly needs something done about it, not just for the running of these events but for the effect it has on grass-roots play," insists Dawson, who referred to slow play as "a cancer in golf." It is one that has continued to metastasize, as evidenced by the pace at the Masters, where the final twosome of Brandt Snedeker and eventual winner Trevor Immelman needed five hours, 10 minutes to traverse Augusta National GC.

Ty Votaw, PGA Tour executive vice president of communications and international affairs, says that discussion centered on how the pro game may impact pace at the amateur level. No decisions were made, except to begin gathering more data in earnest. "The people around the table, the board members of the World Golf Foundation—whether they represent the PGA Tour, the LPGA, the RA, USGA—need to have input. The mission of the World Golf Foundation is to bring the world of golf together, promote it and grow the game, and to lead it, so the subject of pace of play is a pertinent one."

Dawson is the lead voice in fretting over potential trickle-down effect from the tour pros, but Finchem was not sure there was a correlation between professional and amateur pace of play. Among the pros, some are more concerned about the issue than others.

"I don't see slow play as being that big an issue," Phil Mickelson says. "Thursday and Friday it will be because we have a lot of players, and it's just a fact of life. I don't see it as a problem."

Rory Sabbatini, who has been vociferous and demonstrative in opposition to slow play, disagreees. "We all know there is a problem. This isn't a new subject," he said. "There is a policy in place, and the answer is that we simply should enforce the policy. I don't know if anyone is really prepared to do that."

Tiger Woods hasn't played since the Masters, but he chimed in recently on the subject via his website. "I know this is a complicated issue. Hopefully, it can be addressed in the near future."

In truth, it was addressed long ago.

It is there in the Rules of Golf. Rule 6-7. "The Player must play without undue delay and in accordance with any pace of play guidelines that the Committee may establish." Breach of the rule calls for penalty strokes in medal play, loss of hole in match play.

Vagueness cripples this entry; undue delay is irrefutably subjective. That is not to say administrators aren't checking their watches. But USGA officials have become sheepherders pushing players to get "back in position," which is on the heels of the group in front, rather than acting as time cops. In fact only three U.S. Open competitors have been assessed a one-stroke penalty for slow play: Bobby Impaglia in 1978, Sam Randolph in 1987 and Edward Fryatt in 1997.

It's no different on the PGA Tour. A concerted effort is made to maintain flow, yet actual pace goes largely unchecked. The tour's pace-of-play policy entails cumulative fines, starting at $20,000, for players who receive 10 or more bad times in a season. Players aren't timed unless their group lags more than a hole behind the threesome in front of them, in which case they are informed they are on the clock. The first player to hit is allowed 60 seconds, and the others get 40 for each shot. If a warning is issued, it is assessed to all members of the group. A second bad time during a round results in a one-stroke penalty and a $5,000 fine. But that hasn't happened since Dillard Pruitt—who is now, ironically, a tour rules official—got dinged at the 1992 GTE Byron Nelson Golf Classic.

This is odd when you consider what Mike Davis, senior director of rules and competitions for the USGA, says about penalties: They work. "The argument can be made that you start penalizing and players will pick up play," he says. "We've seen that in our amateur championships for stroke play."

Conversely, absent the threat of the penalty hammer being dropped, and with slower players somewhat protected by the group and by the field at large all moving deliberately, a pace of play is established from which there is little deviation from week to week, except when it slows even more. And there has been a notable slowdown in the last decade.

Empirical evidence provided by the PGA Tour indicates that threesomes averaged four hours, 34 minutes on Thursdays and 4:29 on Fridays in 1997. By 2001 those averages had increased 14 minutes, to 4:48 and 4:43, respectively. They have since leveled off, though '06 was a bright spot when threesomes shaved rounds to 4:42.

Not coincidentally, low-speed golf corresponds to advances in equipment, including drivers with larger, titanium heads and golf balls with improved aerodynamics. The upshot was more short par 4s were drivable and more par 5s became reachable in two shots as average driving distance on the PGA Tour exploded. In 1997 12 players averaged 280 or more yards off the tee. By 2000 the number had increased to 29. In 2001, after the introduction of the Titleist Pro V1 and similar multilayer balls, there were 89 players at that distance. This year, through the Crowne Plaza Invitational, 132 players sport an average driving distance of at least 280 yards.

The pushback to this has manifested itself in courses being made longer. Consider the evolution of Augusta National GC, arguably the world's most renowned course. It measured 6,925 yards in 1997 and by 2002 it was 7,270 yards. Since 2006 it has played to 7,445 yards. This year's Open at Torrey Pines, reconfigured to par 71, measures 7,643 yards—379 yards longer than any previous Open course.

In lockstep course setups have become more arduous, or, some players might say, tricked up: fairways narrowed, the rough higher, greens firmer and faster, and hole locations inching nearer the edges of putting surfaces.

"My whole issue with slow play relates to the golf ball," says Jack Nicklaus, who has been advocating a rollback for years but in the meantime has been forced to preside over continual upgrades to his Muirfield Village GC, in Dublin, Ohio, site of last week's Memorial Tournament. "As you've made the golf ball go farther, you've got to make the golf course longer to fit what the golf ball is doing. When you make the golf course longer, and you also are trying to make it harder to have it be an appropriate test, it takes more time to play it."

"When the rough is deeper and the greens are like cement and the hole locations get closer to edges, you can't just expect guys to step up and hit it," says Mark Russell, tournament director for the PGA Tour. "They can't just wave it in the hole. We have made courses more challenging."

Sheer number of competitors doesn't help. In a full field of 156 players, the tour's two-tee schedule requires 13 sets of threesomes to tee off on Nos. 1 and 10 in morning and afternoon waves. "There aren't enough golf holes for all the guys that have to be on the course," says Russell. "We can send the numbers to MIT, and it would take a second for them to tell us the math doesn't work."

Russell says that more than just better pace results from fewer players. "You get a smaller field like an invitational (which are limited to 120 players), and the slow players stick out like a sore thumb," he said, estimating that the tour's tortoise population numbers roughly 20. "You know which guys are holding up the field."

If that's the case, why not start assessing penalties?

"Slow play was a problem before I got on tour, and it's never going to go away," Ryder Cup captain Paul Azinger says. "There's too much money at stake, and with the system in place, you almost have to have an outside entity police the field every week. Our officials do not have the authority, nor do they want the authority, because they understand what's at stake, and they're not going to pull the trigger on a one-stroke penalty when it means that much."

Indeed, money also has had a stultifying effect. In '97, at the outset of the Tiger Woods era, the PGA Tour's total purse was $80.5 million. In 2000 that figure had more than doubled to $164 million. This year's take approaches $280 million. Obviously, there are plenty of good reasons for competitors to heed the advice of their sport psychologists and not hit a shot until they are "fully committed."

J.B. Holmes recently sized up the situation succinctly. "You're playing for $1 million. If someone thinks I'm slow or taking too long, I don't care."

Never mind that this might be to the detriment of other players. Which could have an adverse affect on scoring, which further impedes progress. It seems like all roads lead to slower rounds.

"We have almost a cart mentality to how we approach pace of play," former British Open champion Todd Hamilton says. "We're not ready to play when it's our turn. And then we go through our whole routine, and we just waste a lot of time, and who knows how that affects your playing partners or other guys behind you. The length of time we're taking … it's like we're using cart-path only rules."

"I think I play better when I play faster," says 2006 U.S. Open champion Geoff Ogilvy. "I think just about everyone, being honest, would say they play better when they play faster. So why we don't all just play faster is kind of a mystery."

It is, but it isn't. Says one player, jokingly, "I know how we could play faster. Cut the purses in half, run the greens at 7 [on the Stimpmeter], and put the pins in the middle of every green, and we'll play under four hours."

None of that is going to happen, so better policing, as Azinger suggested, is needed. The merits of that concept are being realized at the junior golf level (see page 61), and Davis says it has helped to have a rules official walk with each group during competition to try to keep the group in position and avert a problem before it develops, a practice the USGA started in the 2006 Open. "We're telling our officials not to wait. If they think their group might be getting out of position, then they should say something," Davis says. "Because of that we've put fewer groups on the clock and we think the pace as been much, much better."

But it is still slower. A sampling of records kept by Jeff Hall, the USGA's managing director of rules and competitions, shows that the fastest threesomes in the 1998 U.S. Open took 4:24 to play Olympic Club, and in 2002 at Bethpage State Park, the quickest were buzzing along at 4:46. Last year at Oakmont CC, the best any group could manage was 5:04.

Given the difficulty of a U.S. Open layout, Davis thinks 4:45 is not an unreasonable time for three long-hitting, skilled golfers to complete 18 holes. In fact, the recommended allotted time for the opening two rounds this year is 4:40. For twosomes on the weekend, it's 4:03.

Compare that to just 10 years ago at Olympic Club, when the USGA's allotted time for the final two rounds was 3:36—27 minutes fewer.

Speeding Up The Game Starts With Junior Golf

"Players will play as slowly as you allow them to. They don't really have internal clocks."

Stephen Hamblin, executive director of the American Junior Golf Association, speaks from experience when analyzing the dynamics of laggardly pace of play at certain levels of tournament golf. Competitors need to be timed, pushed along and held to a reasonable standard, or else everyone is in for a long day.

Hamblin, who feels a "moral responsibility" to the game to teach young players about all the tenets of etiquette, including pace of play, can draw from anecdotal evidence. Since installing a timing-station system at AJGA events, the duration of rounds has been reduced. The system entails six checkpoints. Red cards are designated for players who miss the checkpoint times. A second red card results in a one-stroke penalty for each player in the group.

"We don't need a harassing environment. The players dictate their own fate," says Hamblin, who last year saw the pace of play for threesomes over the 82 tournaments the AJGA conducted, average four hours, 28 minutes.

The USGA has adopted the system for 10 of its amateur-only tournaments. Colleges also are starting to experiment with a similar system. Mike Davis of the USGA has sensed for some time that college golfers might be the slowest players in the amateur ranks. Georgia Tech golf coach Bruce Heppler wouldn't disagree. He says they fall into bad habits -- because they are allowed to.

"No one should knock the college player per se," Heppler says. "He plays as fast as he needs to. But they have no real idea how fast they play, and at most college events we lack the resources to monitor it."

So it comes down to the fact players need policing. The AJGA system might be the answer for all levels. Hamblin recently instituted it at a Texas A&M University event. Coach J.T. Higgins insisted that no threesome had ever toured the difficult University Course in less than five hours. This past year with the checkpoint system, threesomes averaged four hours, 40 minutes.