The Best Of Golf DIgest

A Final Visit with Seve Ballesteros

This is a new series on the 70th anniversary of Golf Digest commemorating the best literature we’ve ever published. Each entry includes an introduction that celebrates the author or puts in context the story. Catch up on earlier installments.

Jaime Diaz is one of the sport’s deep thinkers, whether writing features for Golf Digest, which he has done since 1989, or doing commentary on Golf Channel, his full-time gig now. He has a knack for observation and historical perspective that’s simply better than any of his contemporaries’. Jaime can dissect the mechanics of a tour pro’s swing as easily as he analyzes the closing holes of a tournament or explains the parental relationship that forged the character of a major champion. And he does it all with the empathy of a poet engaged in his own human struggle for golf’s tough love.

There was no better writer for explaining Seve Ballesteros, especially at the end of Seve’s life, when genius faced reality. I asked Jaime recently what he remembered about this piece that appeared in July 2010, and he replied: “For all of Seve’s triumphs, it seemed I wrote about him most during times of loss: his crushing defeat at the 1986 Masters, the free fall of his game in the ’90s, the poignancy of his last Open Championship, at Hoylake in 2006. Occasions when he was exposed and fragile. But contrary to his reputation for combativeness, he had handled such moments with honesty that struck me as noble.

“When photographer Erin Patrice O’Brien and I visited Seve in April 2010, he was fragile in life—physically and emotionally. Yet on a day when his nephew Ivan would warn us that his uncle’s energy was particularly low, Seve’s effort—fierce but discreet—was touching. During our interview, though it caused him tears more than once, he went to deep places and got the words right. The brain operations had left him a bit unsteady on his feet, but he insisted on guiding us through several rooms in his elegant home, lingering on a nautical motif that was a tribute to his late father, Baldomero, a local rowing champion. When his face inevitably began to betray a heavy fatigue, he stood with a determined smile to complete a rushed but successful photo session.

“Throughout, while Seve spoke positively about his recovery, it was impossible to ignore the specter of ultimate loss. Two months later, he would follow the recommendations of his doctors and cancel his trip to participate in the four-hole Champions Challenge before the Open at St. Andrews, a decision I learned he came to regret until his death at 54 in May 2011. My lasting memory is that on the last day I ever saw him, more than ever, Seve was noble.”

At the end of this article, there’s a link to a final tribute column that Jaime wrote after Seve’s passing. It’s also worth the trip. —Jerry Tarde

Seve Ballesteros' home in Pedrena, Spain, is built on a promontory above the beach where as a boy he hit pebbles with a wood-shafted 3-iron, and it's only a few hundred yards from the converted farmhouse where he was born. It's a three-story medley of tasteful masonry, earth-toned stucco and dark wood, understated in every way. Except one.

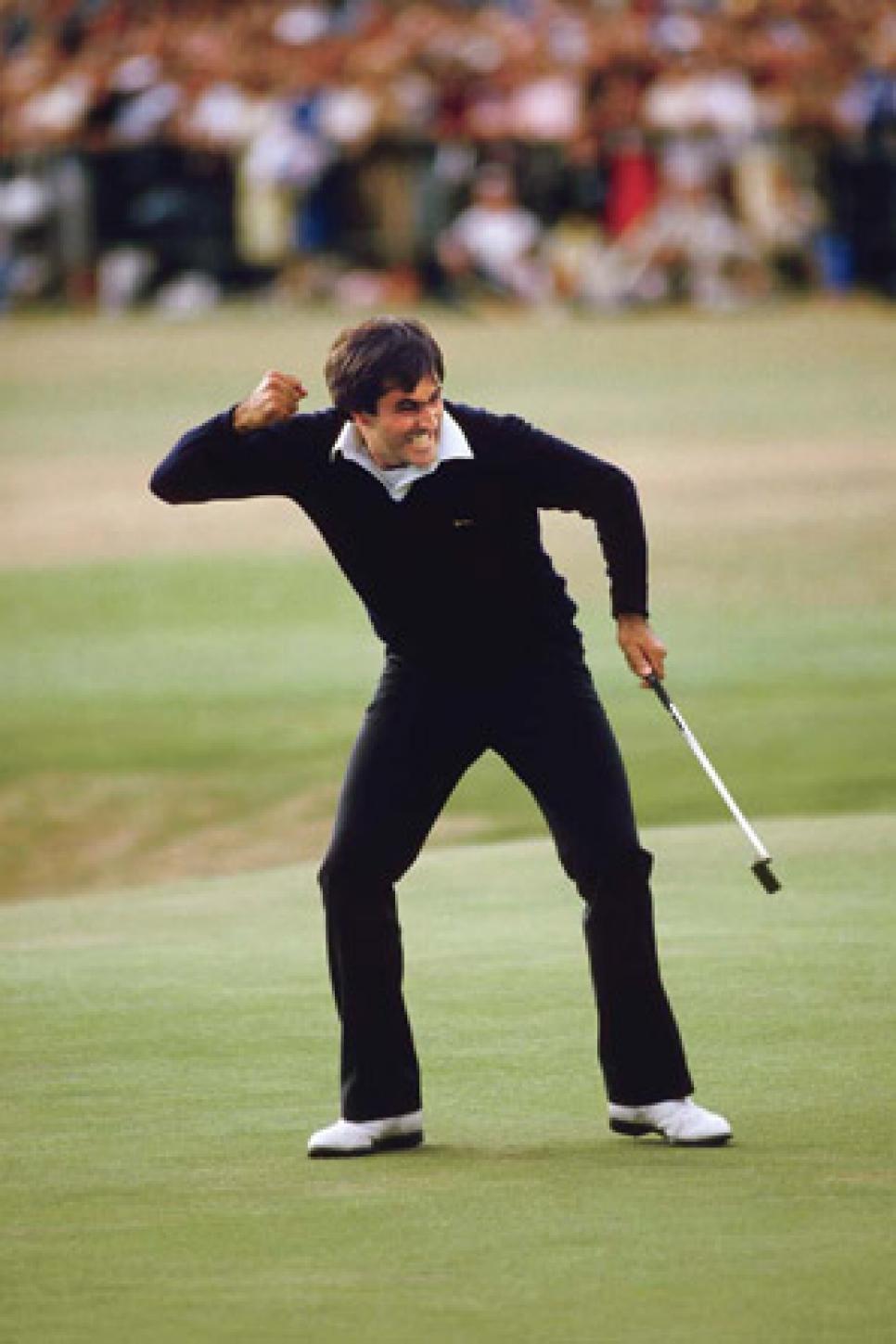

A silhouette in weathered bronze of the golfer reacting to his winning putt at the 1984 British Open at St. Andrews is mounted on the front door.

The depiction is often referred to by Ballesteros' inner circle as El Momento, and he calls it "the greatest moment of my career." It serves as his business logo, appearing on all manner of products, and Ballesteros even has it tattooed on his left forearm. But after the cruel blows he has endured the past several years, it has become a haunting symbol of a pinnacle too brief and too long past.

The combination of magic and misfortune is why Ballesteros' anticipated return to the Old Course at this year's British Open will prompt the warmest display of mass public affection any golfer has ever received. Engaged in a battle with brain cancer, Ballesteros says he will play in the four-hole Open Champions' Challenge the day before the tournament starts. Given his illness, his standing as the most beloved European golfer ever among British fans and that the first tee at the Old Course is the game's most iconic stage, the announcement of his name and his opening tee shot will be golf's version of Muhammad Ali lighting the Olympic torch at the 1996 Summer Games.

Like Ali, Ballesteros, 53, has been physically diminished. Doctors discovered a malignant tumor the size of two golf balls above his right temple after he fainted at the Madrid airport on Oct. 5, 2008. Over 11 days, he would undergo three complicated surgeries totaling more than 20 hours to remove as much of the tumor as possible. After 22 days in intensive care and 72 days in the hospital, Ballesteros emerged with an unsettling diagonal scar where the main incision had been made. Once back home, he embarked on 12 treatments of chemotherapy, followed by two months of radiation late last year.

Although still too fatigued in late April from the after effects of the radiation to play golf, Ballesteros agreed to allow Golf Digest to come to Spain to discuss his recovery and his life. We met in the foyer of his home, and although his torso has lost some of its sturdiness and his features some of their expressiveness, his innate charisma still allows him to cut a noble figure.

"Hola," he says, his voice unchanged. "Many years since you've been here."

It was a reference to a visit I made in 1990, when after initially annoying Ballesteros by appearing unannounced at the Royal Golf Club of Pedrena, he graciously agreed to an impromptu interview. "This house wasn't built yet. A lot of things are different."

It was indeed a whole other time. When Ballesteros won at St. Andrews he was 27 years old, and it was his fourth major championship, putting him on an early trajectory no player other than Tiger Woods has equaled since.

In Ballesteros' victory at the Old Course, he had taken the top spot in the game from Tom Watson, who had succeeded Jack Nicklaus. Ballesteros seemed well on his way to establishing his own era.

He had wondrous tools, combining the physical talents of power, shotmaking ability and a genius short game with the mental strengths of ultra-fierce competitiveness and a keen "golfing mind."

But what made Ballesteros truly special was an ability to connect with spectators. Part of it was his gift for improvising some of the most improbable recovery shots in the history of the game. "He was to the short game what Hogan was to ball-striking," says Hank Haney. Another element was the pure passion with which Seve performed. That was never more evident than in his ultimate "moment" on the final green in 1984. When the 15-foot birdie putt barely crawled into the high side of the hole, Ballesteros began a series of right-hand thrusts into the sky that also served as salutes to the cheering multitudes packed in the grandstands and straining to watch from the balconies of the Auld Grey Toon.

"I loved the expressive way he played, like Arnold Palmer," says Ben Crenshaw. "When he did well, he showed it in a beautiful, proud way. When he failed, he did it with so much heart that people would feel for him. When he won at St. Andrews, that's one of the great reactions in the history of the game."

Somehow, the moment didn't prove to be a springboard. Ballesteros won only one more major, the 1988 British Open, finishing with three Opens and two Masters. At first gradually, and then very quickly as the condition of his lower back deteriorated, he lost the length and especially accuracy in his long game. Even as his wedge play and putting remained in the all-time category, he didn't have enough game to get in contention with any regularity, and he won his final official tournament in 1995. He played on for another mostly desultory dozen years, and although he ended up with more than 90 professional victories around the world, a record 50 on the European tour and almost single-handedly elevated the Ryder Cup into one of golf's premier events, his career leaves the feeling of loss.

It's a sensation that pervades his current life on a few levels and is palpable in his large house, where he lives alone. Ballesteros and Carmen, his wife of 16 years, divorced in 2004. Their three children -- Javier, 19; Miguel, 17; and Carmen, 15 -- live in Madrid with their mother and visit Ballesteros regularly, but he admits the place he once called "my paradise" contains too many echoes for a sole occupant.

PARTIAL PARALYSIS

After our greeting, he leads me into his spacious living room, with large windows opening to views of the Bay of Santander. His gait has lost its smoothness, and he explains that because of damage from the tumor, he has suffered partial paralysis on his left side. "I don't have very good balance because my left leg has lost some feeling," he says. "My left hand is worse. When I have something in the hand, the keys or a glass of water, I don't know if I have it or not. Some of it might come back a little bit, but not like before." During our conversation, several times his left arm slides off its resting place on his knee, causing him to reflexively pick it up with his right hand and put it back in position.

Ballesteros has also lost about 75 percent of the vision in his left eye. Because I unthinkingly sit on his left, he has to fully turn to look at me, which he does. His eyes seem to open wider than I remember, and he holds eye contact longer.

Ballesteros says that for the moment he has lost some of the energy he exhibited after being inspired by Watson's Open performance last year at Turnberry. Along with the radiation, the cold and rainy winter and spring in northern Spain have kept him from wanting to spend a lot of time outside. "But I'm getting stronger again," he says. "The doctors who saved me, they say that in my treatment I am on the 15th hole. I'm looking forward to finishing this round."

His metaphor leads into questions about the kind of golf he can play after his surgery. Ballesteros still enjoys playing and practicing, and he contends he can still hit some good shots, though he's perhaps 50 yards shorter off the tee, and because of his balance problems on his left side he often finishes in the Gary Player "walk-through" style. Beginning in May 2009, Ballesteros began hitting balls on the range nearly every day, as well as playing occasional nine-hole rounds at Royal Pedrena, where he caddied and which lies in the valley below his house.

"It felt different, very weird," he says of the sensation of first hitting the ball again. "But as soon as I practice a few, the rhythm comes back. And I played last summer, very well. I can hit the ball. I can hit long shots, long irons, medium irons. My short game is pretty good, and I can putt. But aiming and judging distance is a handicap now. Of course, I miss that I lost a little bit of skill, you know. But golf is very good therapy."

He gestures out the window to the nine-hole pitch-and-putt course he installed on his 17-acre property after the surgery. Though no hole is longer than 75 yards, he designed it with wickedly tiny greens that cozy up to streams and ponds and drop off to punish the smallest error. "It's very difficult, yes," he says. "Well, if you make it easy, it's no challenge. I make it for me, and for my friends. If they shoot three or four under, there is nothing to talk about after. The record is one under par. By me."

This last remark is delivered with a familiar jauntiness, but it is not accompanied by the smile or laughter that used to come so naturally. I realize that Ballesteros is now less expressive, a condition not unusual for people who are recovering from major brain surgery. At the same time, overflowing emotion is also a normal aftermath, and when I ask Ballesteros specifically about returning to St. Andrews, his voice thickens and he averts his gaze.

"Yes, I think, well..." As he grimaces and tears come, he covers his eyes with his right hand and waits through soft sobs. "It's all right," he says. "It will go away."

He wipes his eyes and gathers himself before continuing. "My goal was to compete in the championship, but I cannot," he says. "But I think I have the obligation to go and play the four holes. Because of what St. Andrews means. To me and to people. Because of all the British people have done in the past for me. They want to see me, and I have to go out there for them."

His presenting the situation as a burden makes me think of his close friend Vicente Fernandez telling me that toward the end of Ballesteros' career, Seve had confided to him, "I cannot handle the pressure from the people, from the players, from the press. I don't want to act rude to the people, but that's my feeling. I get to the first tee, I'm shaking."

But when I ask Ballesteros if he will feel nervous about his game in the four-hole exhibition, he says, "No, there is nothing left to prove." Asked if he is looking forward to being personally fulfilled by the experience, he again breaks into tears, finally saying, "Emotionally it will be...very strong. As you can see. Sorry."

But even as he excuses himself for breaking down, Ballesteros seems almost relieved to be able to offer a less-guarded version of himself. He knows that since his illness his life has become more of an open book than it ever was as a player, when he fiercely guarded his privacy and was often cryptic in his interviews. He also realizes that he has become an inspiration to many. "It's good to let go, because I have so much emotions," he says. "Because it is so much inside, for a long time, it's good to let it out. I am a very sensitive person. A lot of people think I'm very hard, you know. But you see the sensitive part now. Very sensitive. Very human."

'I DON'T WANT THIS ANYMORE'

That he kept his emotions under wraps for so long makes his later years more painful to consider. For a time, it seemed he was holding on to stay in shape for a successful run on the Champions Tour when he turned 50. But after playing only one event, in Alabama in May 2007, and shooting 78-81-73 to finish tied for last, he abruptly went back to Spain.

"Part of it was I felt homesick in America, similar to how I felt in the early '80s," he explains. "I thought, If I couldn't do it then, why do it now? That was part of it. But something inside just told me, I don't want this anymore. It was time."

Two months later, at the Open at Carnoustie, he announced his retirement from competition. But though he often seemed disconsolate in the last years of his playing career, the medical crisis that engulfed Ballesteros 15 months later snapped him back into fighting mode. Ivan Ballesteros, who assists his uncle in his public life, says that Seve's first words after emerging from the first marathon surgery, spoken in a dream state, were "Yo siempre gano." ("I always win.")

That spirit no doubt rubs hard against some of the significant compromises Ballesteros has had to make in his daily life. Because of his vision problems, he can no longer drive a car. In March, the golf cart he was driving went off a small embankment to his left, causing him to fall out of the cart and hit his head on the ground. He stayed under hospital observation for four days before doctors released him. Nor can Ballesteros ride a bicycle, which as a fan of competitive cycling he enjoyed as his primary source of strenuous exercise. Other than golf, his recreation is limited to walking on the beach, gardening and mild calisthenics.

Ballesteros can depend on his three older brothers. Manuel and Vicente live nearby in Pedrena, and the oldest brother, Baldomero, lives 10 miles away in Santander. Again, tears flow when Ballesteros is asked how his family has reacted to his illness.

"My brothers, my children, I see how much they care about me," he says. "They all respond very good, very good."

He mentions the champions and greats who have called him. "Palmer, Nicklaus, Gary Player -- I don't want to count, because I will forget many. Whenever someone calls, it helps. Arnold Palmer sent me a dog," he says, almost chuckling. "In a picture. His dog, called Mulligan. Because the doctors saved my life, they say now I use my mulligan. So Palmer's picture says, 'Here's a Mulligan for you.' "

And to ease his loneliness a bit, Ballesteros recently acquired a Labrador puppy. After watching Phil Mickelson's victory at Augusta in April, Seve named the newcomer Phil.

Since retirement, Ballesteros has become more interested in his legacy. He says his proudest achievement is making golf more popular in Spain. He is also committed financially and conceptually to two Ryder Cup-style professional events. The former Seve Trophy -- now called the Vivendi Trophy with Seve Ballesteros -- matches teams from Great Britain & Ireland and Europe. Ballesteros says the matches provide valuable preparation for Europe's best in the next year's Ryder Cup. Ballesteros sees the Royal Trophy -- a competition between pros from the Asian and Japan tours against a European team -- as an engine to expand and strengthen Asian golf, much as the Ryder Cup did for Europe. Last year he started the Seve Ballesteros Foundation, dedicated to brain-tumor research. Its blue wristbands emulate Lance Armstrong's "Livestrong" yellow bands. "I admire Lance," says Ballesteros, a close friend of five-time Tour de France winner Miguel Indurain. "It would be wonderful if I could motivate people as he has."

It's when Ballesteros talks about his illness that he is least emotional.

"Through all this, I've never been afraid of dying," he says. "I was more afraid of how I was to face the future. Because maybe I couldn't manage myself. But I feel much better about that now. I don't feel sorry for myself, no. You've got to be strong in life, because it is not fair. You just have to think, This is what I have. I have no other choice. Take it or leave it. So I take it."

The unfairness has also struck his compatriot, Jose Maria Olazabal, who at 44 is in a battle for his career against a mysterious recurrence of rheumatism. Olazabal, who lives near San Sebastian, visited Ballesteros in the hospital and continues to do so in Pedrena. Asked about his friend, Ballesteros' voice grows husky again.

"I call him three days ago, to see how he's doing, and I tell him to be strong, to be patient, that the bonus will come," Ballesteros says. Asked for Olazabal's reply, Seve struggles. "Well...he says he and I were both tough competitors. And that we never give up. And he says that we are going... to win."

Ballesteros shakes his head after the tears stop. "I have more feeling for other people now," he says. "Because a lot of people help me. Not only my family and friends, but a lot of people from all over the world. They don't have anything with me. But they send me notes. And give me calls. And bring me things. That was like, Hey, wake up, you know. If people love you and they hug you, now is your time to do the same. Something like that."

He asks about Ken Green, who once angered Ballesteros over a crucial ruling on the final nine of the 1989 Masters, and he wants to know how Green is recovering from a terrible RV accident: "I hope he is better." And Ballesteros expresses empathy for Tiger Woods: "You know, when you win special tournaments and you become a superstar, the first thing you lose is your freedom. That's big. That's hard. It's hard for others to understand. But, you know, you have to pardon people. Otherwise, you will never be free."

The anger that for so long fueled him seems to have dissipated. As recently as his 2007 autobiography, Seve (translated to English by Peter Bush), Ballesteros took shots at just about every institution of authority in his life -- including Royal Pedrena, the Royal Spanish Golf Federation and the European and PGA tours -- all for various slights. He also defended himself against accusations of gamesmanship and called rumors that infidelity broke up his marriage "vicious," writing, "neither Carmen nor myself had any affairs while our marriage lasted." But now he emphasizes gratitude more than grudges. "I've had a tremendous life," he says. "Tremendous things happen to me over the years. When you win the Masters or the British Open or the World Match Play, the following week, you know, the feeling inside is so good. So I've had that kind of peace. The peace I am finding now, it's not about competition. It's different."

The questions that seemed so unanswerable during most of Ballesteros' playing career he now solves with quick answers. He attempts to put an end to all the speculation about how he helped derail his prime by experimenting with too many swing theories and teachers, asserting that all the problems he had with his swing can be traced to a lower-back injury he suffered while boxing with a friend at 14.

"The back was the only reason my game and my golf swing would deteriorate progressively," he says. "The only reason. To change the swing is not that hard if you have talent, but you have to be very good physically. I wasn't. I couldn't do it. With the driver especially, the back was more involved, and there was more pain." Sounding more like Hogan, he adds, "There is no secret in golf that a teacher can give you. You have your own way, your own vision and your own feeling. If you practice constantly, that's the secret."

BIGGEST REGRET: 1986 MASTERS

Asked about his regrets, he deadpans, "Second shot on 15 at Augusta -- I make 6." In that fateful last round in 1986, Ballesteros was leading before dunking a fat 4-iron shot into the pond and ultimately losing to Nicklaus, and Seve doesn't disagree with those who have opined that it was there where his career lost momentum. "I lose the finishing punch," he says.

Ballesteros says the reason the disappointment and diminished confidence lingered was because he had failed to win for the memory of his father, who had died of lung cancer the month before at 67.

Baldomero Ballesteros Sr. was a local champion oarsman, with the same long arms and strong will as his youngest son. Seve felt a kinship with the man who had most helped him feel special, and he took great joy in showing his appreciation.

"My father was a fighter, and he would never give up," Ballesteros says. "We were pretty close. He always encouraged me. I loved to take him with me in jets or limousines and let him drink whiskey and share my success. He would say, 'Oh, Seve, this is the life!' After he died, the hardest thing was when I was winning tournaments I used to call home and he...wasn't there."

Now, Ballesteros has a date with the Old Course. After his initial bout with emotion, he is expansive.

"The first time I played it, I didn't like it," he says. "I thought it was ugly. But the first time I played it with a little bit of breeze, I loved it. It's an incredible place, and an incredible course. But there must be a little bit of wind. That's when you have the challenge. Then you play all the clubs and all the shots you have in the bag."

He played well in 1978, leading by two strokes until he hit into the hotel and took a double-bogey 6 on the 17th in the second round, finishing the tournament T-17. In 1984, during practice rounds, his friend Fernandez encouraged Ballesteros to take the club a bit more on the inside to counteract a tendency to let his right elbow wander too far from his body. "Chino give me a little tip on my swing," he says, "and I stick to that and each day played better and better."

He started the final round two shots behind Watson and Ian Baker-Finch, who were paired in the last group.

"Watson was the best player in the world at that moment," Ballesteros says, "and he was trying to tie the record of Harry Vardon: six British Opens. He was under a lot of pressure also. We were not close, but champions in the same category never are close. You never see both go outside for dinner. Never. That's not because it is personal. The competition carries on, not just on the golf course, but off the golf course also. It was that way for me and Watson."

In the last round, "I played very steady," Ballesteros recalls. "I didn't do anything spectacular, but I played very steady and very solid, especially on the back nine. I birdied 14, then a fantastic par on 17, where I put my 6-iron on the middle of the green from the rough on the left side. That second shot was like a tunnel, you know."

On the 18th, Ballesteros hit a conservative 3-wood off the tee and then a wedge into the green.

"The putt, breaking six inches, I hit it well," he says. "As the ball was approaching the hole, I was more and more hoping, and it dropped in. I think with my interior energy, I put it inside myself. I think so. That was the greatest moment of my career."

He has been back to the hallowed ground to play three British Opens since then, but never with so much anticipation. When Bobby Jones returned to St. Andrews for the last time in 1958, he was suffering from a crippling disease of the spinal cord. After Jones was honored during the Freedom of the City and Royal Burgh of St. Andrew ceremony, a filled auditorium began singing an old Scottish song, "Will Ye No' Come Back Again?"

"It had all the strange, wild, emotional force of the skirl of a bagpipe," wrote Herbert Warren Wind. "Hardly a word was said as the people filed from the hall, and for many minutes afterward it was impossible for anyone to speak."

When asked what he will feel when he is announced on the first tee, it is Ballesteros -- his face scrunching but his gaze steady -- who cannot speak.

He doesn't have to. It will definitely be a moment.

Editor’s note: Jaime’s Diaz’s column after Seve’s death on May 7, 2011: