From the Magazine

The New DJ

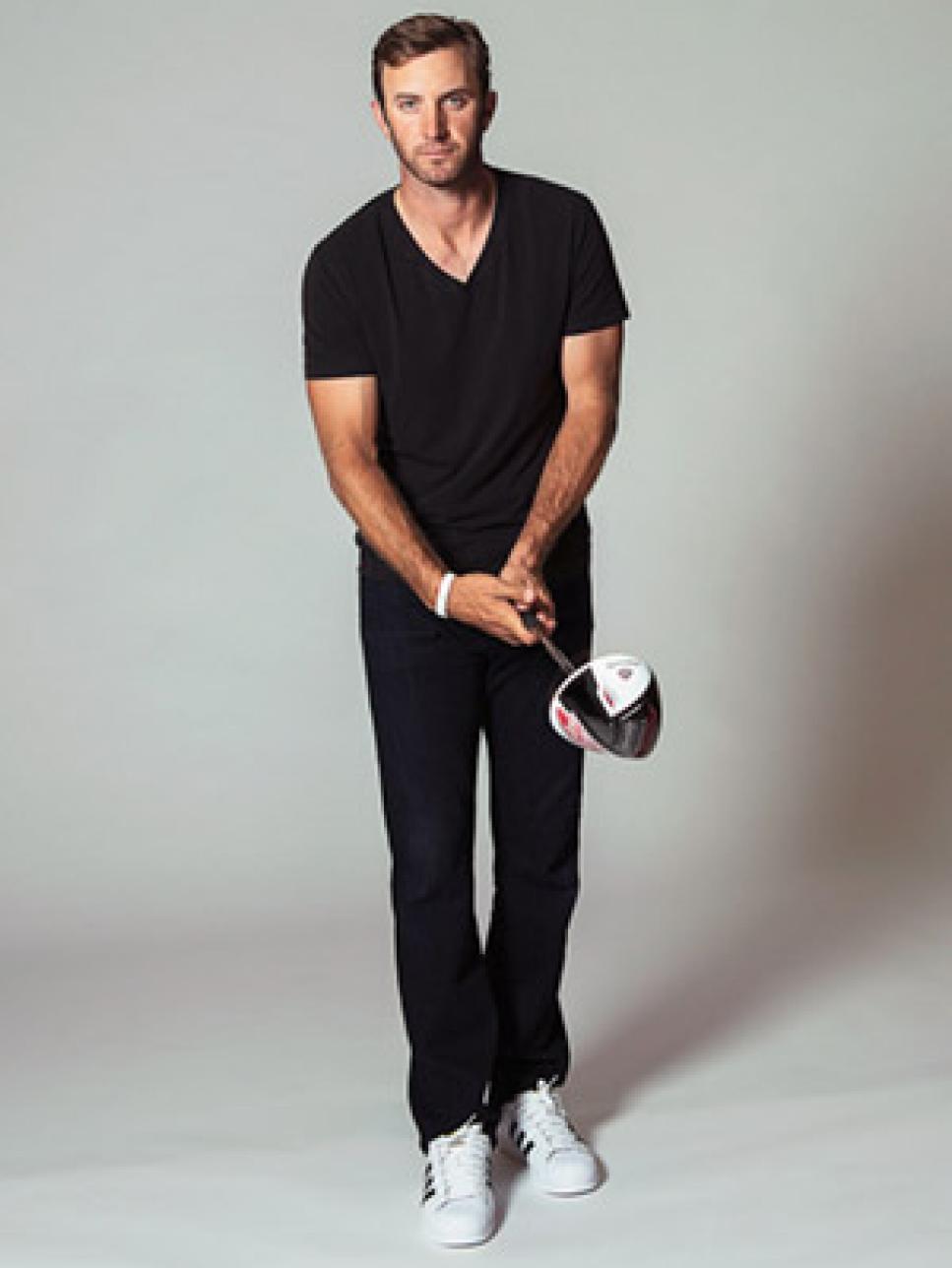

In different ways, Dustin Johnson is all about distance. Sheer physicality makes him a man apart.

He's a clear winner of the genetic sweepstakes: long and sinewy at 6-4 and 208 pounds, wide and narrow in the right places, with a loose-limbed walk that, like the boy from Ipanema, "swings so cool and sways so gentle." His trainer, Joey Diovisalvi, says, "Whatever he does, DJ is like a prototype.

When he's in the pool doing flip turns, he looks like Michael Phelps. Playing basketball, he's got a stroke like an NBA shooting guard. On a road bike, he could be wearing the yellow jersey. He'll perform a very technical Olympic lift with perfect form. He could do a triathlon tomorrow. As far as golf, his biomechanical efficiency makes him a human version of Iron Byron. I've never worked with a pro golfer who is such a gifted multi-sport athlete."

There's the sheer distance Johnson hits the ball. Though he led the PGA Tour in driving distance at 318.8 yards going into the Masters, many insiders consider him the big hitter who holds the most in reserve. The coil, extension and especially the position of his right elbow in the hitting area—past his right hip—are freakish power producers. "Why try to hit it 350 when you can hit it 330 with control?" asks Johnson's younger brother, Austin, his caddie since 2013. "He's got another 30 in there when he wants it."

Then there's the distance Johnson is striving to put between himself and the rest of the field. His victory at the WGC-Cadillac in March gave him nine career wins in 163 starts—only Tiger Woods, Rory McIlroy, Phil Mickelson and Vijay Singh among current players have a better win ratio. Johnson is also only the fourth golfer (Palmer, Nicklaus, Woods) to win in each of his first eight seasons, the longest current streak on tour. Quietly, he's intent on overtaking McIlroy at No. 1.

Johnson is normally reserved, but he was emotional after closing out the victory at Doral with what for him was a soliloquy: "I knew I was really good, [but] I knew there was something missing that could make me great," he said. "I'm working hard on that, and I think it's showing. I'm so excited right now, I can't hardly talk. This one definitely, by far, is the best one."

More complex, there's also the distance Johnson has kept between his past and present. It has been that way since his difficult early years in South Carolina. He was brought up by his paternal grandmother after his parents contentiously divorced, and there was a conviction at age 16 for second-degree burglary for being involved in the theft of a handgun that was later used in a murder. He was pardoned in 2009, but later that year he was arrested for DUI, which was dismissed when he pleaded guilty to reckless driving.

Lately, Johnson has tried to elude parts of the recent past. Last August, he announced he was taking a leave from the tour "to seek professional help for personal challenges." Later, golf.com cited unnamed sources who said the leave was because Johnson had been suspended for failing a third drug test, and his second for cocaine. Johnson, who turns 31 in June, denied he had ever failed a drug test, and the tour denied he had been suspended. He admitted he sometimes consumed vodka to excess but has denied he had a drug problem. "I have issues," he says, "but that's not the issue."

It has been a lot to deal with. Johnson took on a life coach during his absence and is showing more self-awareness. "I had a lot of stress, but I really didn't know," he says. "It had to do with everything—everything with life. You know, it helps to talk about it. It's been interesting. It helps that my life coach has a perspective that's outside my inner circle. He can see things more clearly."

More structure has also helped. In October, Johnson embarked on an ambitious seven-days-a-week workout regimen, and he has stuck with it under the direction of Diovisalvi.

"Getting in the gym helps your mental game more than anything," Johnson says. He also hired a nutritionist whose meals have carved off 12 pounds but added muscle. Most important, Johnson became a father on Jan. 19, when fiancee Paulina Gretzky gave birth to son Tatum Gretzky Johnson.

It has all had a visibly dramatic effect. Johnson looks livelier, his distinctive saunter featuring better posture, his stylish clothes fitting him even better. He shaved his full beard, though his ability to grow another one within a week is why his brother sometimes calls him "Chia Pet." Most noticeably, he's more responsive to others. "DJ's glassy-eyed avoidance look—that's gone," said one acquaintance. "He's way more present. It's like he's a different person."

And perhaps, not coincidentally, a different golfer. Since returning to competition, Johnson has been on one of the most consistent runs of his career. Most memorable was his final drive on the 18th at Doral, a bomb down the left side into a breeze, carrying the perilous inlet of water that narrows the fairway at 310 yards. With a one-stroke lead and bailouts to the right de rigueur, it was a statement shot.

"Dustin knows how good he is, and he's always had the desire to be better," says instructor Butch Harmon. "He hasn't known quite how to go about it. Taking responsibility in his life has made a huge difference. I see a guy who is calm, comfortable in his skin, happy. It's been nothing but good for his game."

The image hasn't quite caught up. Johnson's controversial absence acted as a reminder of his checkered history. He was portrayed in social media as a party animal, with racy Instagram shots with Gretzky as Exhibit A. It created a negative prism through which to evaluate his fourth-round 82 after leading the 2010 U.S. Open at Pebble Beach, the club-grounding penalty on the final hole of that year's PGA at Whistling Straits that cost him a spot in a playoff, and his flared out-of-bounds 2-iron that handed the 2011 British Open to Darren Clarke at Royal St. George's. Moreover, perennial stats that got worse the closer he got to the green reinforced a portrait of a challenged talent. A Taiwanese animation parody even called Johnson "so dense light bends around him."

CALIFORNIA COOL VERSUS CONFLICT AVOIDANCE

His peers perceive a different guy. Between the ropes, Johnson has always been well-liked. He's admired for his skill, fearlessness and athleticism. Blending Southern swagger with California cool, Johnson's trademark greeting is "Yo, bro." It's common on practice ranges to see players and caddies around him chuckling at his observations. "Everybody loves DJ," Geoff Ogilvy says.

Then again, conversations don't get particularly intimate among competitors. Which is a distance that suits Johnson. He has resisted the increasing media inquiries specific and general with vague and evasive answers. "That's Dustin's conflict-avoidance mechanism," says Allen Terrell, Johnson's coach at Coastal Carolina who now runs DJ's golf schools. "Sure, some things are nobody's business. And when you're a top-10-in-the-world superman, and someone wants to talk about your weaknesses, you develop a little chip. But he's starting to understand that how he portrays himself is how he is going to be perceived."

It's a process. For a recent interview on the patio of a hotel in San Antonio, Johnson approached in long strides as soft as those of a big cat, extended a large hand and then folded his frame into a too-small lounge chair in which the spillover somehow didn't seem uncomfortable. He kept popping up to spit out tobacco juice from dip.

Johnson was cooperative, making eye contact and contributing to light banter, but it's not his nature to look inward. When prodded to do so, his classic laconic-sports-star cadence becomes more halting. With a wingspan longer than his height, arms-length from Johnson is a ways.

Johnson's favorite escape is a pithy phrase that qualifies as a telling answer. At one point, when asked to react to a comment made about him, he thought for a moment before saying, "I don't know.... I do me."

There's half a lifetime in those last three words. Defiance for those who have been quick to judge him. Reluctance to become close to people who might let him down—or those he might let down. And determination to remain a lone wolf who has managed, against considerable odds, to find his way. "See, that's my deal," Johnson says of his mantra. "I do me. Always have."

Others noticed. "Dustin just has that ability to survive when he has to," says Art Whisnant, his maternal grandfather, who at 6-5 and as a former All-ACC basketball player at South Carolina sees much of himself in Johnson. "Whenever he's been in a tough place, he's found his way clear."

PICKING GOLF OVER TEAM SPORTS

Johnson's refuge was sports. He was bigger, faster and more coordinated than the other kids, but trust issues made him a frustrated teammate. "I was a pitcher and shortstop in Little League, but we didn't have a very good outfield, so when I wasn't pitching and our pitcher was getting hit, I'd go to center field and just take every ball I could reach. In basketball, I was a 'point center'—I'd bring the ball up and then play in the middle on defense. If I got a rebound or blocked a shot, I'd go coast to coast." (Johnson can still dunk easily, and in March he beat former NBA player Shane Battier in a three-point-shooting contest.)

Johnson gravitated to golf because of its self-sufficiency. His father, Scott, an excellent high school athlete who had become a club pro, took Dustin to the Weed Hill Driving Range in Columbia, S.C., when he was 6. "Little DJ had a swing with rhythm and tempo, and he could hit the fool out of the ball," says Jimmy Koosa, the longtime operator and teaching pro at the facility. When Dustin chose to concentrate on golf at 13, he did so as a fully developed athlete, with a massive turn, huge arc and speed. "It was an advantage for Dustin to play other sports when he was young," Terrell says. "Too many golf kids over-specialize and don't develop athleticism."

Johnson's teenage action featured the dramatically bowed left wrist that distinguishes his top-of-the-swing position. Koosa didn't change it. "The way I looked at it, it was basically just an early squaring of the club, because his wrist was going to be like that at impact," Koosa says. "Hogan called it 'supination,' and Trevino put it in a similar position at the top. I could see he could repeat it, and that being able to do that was a sign of real talent." Johnson's subsequent instructors, including Terrell and Harmon, have followed suit. "Dustin has a lot of swing awareness and ownership," Terrell says. "He's not super dependent on instructors and instruction."

Although Whisnant says, "I've never seen that boy mad, or want to fight, ever," Johnson has a fierce competitive drive, pouring his identity into his game.

"Dustin's not afraid to walk into the arena, because he has that thing where he never thinks he's going to lose," Koosa says. "But I call him huggy-kissy tough. He has a nice attitude, not ever a mean boy, never disrespectful." Harmon agrees with the core assessment. "DJ just knows how to compete. He's not afraid of anything—any shot at any time, any player at any time."

But unlike most athletes who burn to win, Johnson is able to forget disappointments quickly. "DJ is a roll-with-the-punches, bounce-back kind of person," Terrell says. "That comes from his perspective. He's gone through enough things in life that bogey isn't the end of the world. That quality can sometimes make it look like he doesn't care, but it gives him good balance. Because he's also a one-up-you, anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-better kind of guy. Win or lose, you really can't get him down. He never beats himself up. There is no negative self-talk in that kid."

Johnson's positive demeanor contributed to getting a golf scholarship to Coastal Carolina despite poor attendance in high school. "I saw it more as giving an opportunity to a person than to a golfer," Terrell says. But the coach treated the student as a project because "any structure at that point was going to be hard for Dustin."

"Coach Terrell was a hard-ass, he really was," Johnson says. "He was hardest on me of all the players, for sure. He saw I needed it, and I'm sure I did. But I would never let it bother me."

Johnson was a two-time first-team All-American at Coastal Carolina, where he is a few credits short of graduating, and played in the 2007 Walker Cup. He then turned pro, and got through three rounds of Q school. In danger of losing his card in his rookie season, he pulled out a late-season victory. A pattern of a super-gifted/marginally dedicated player had begun.

Hard partying is an accepted part of DJ lore. With more success came more toys. Over the years he has acquired an Aston Martin, boats and Jet Skis. He had a particular weakness for high-fashion suits, accumulating some 30 Prada and Dolce & Gabbana ensembles in 41 long, although he estimates half still have the tags on them. When Johnson started dating Gretzky in 2013, he gained an e-ticket to the jet set and its excess. "DJ had a hard time separating his professional life from his private life," Harmon says. "He lost some focus." Johnson was passed over as a captain's pick for the Presidents Cup team in 2013. Motivated, he won in China.

But by mid-2014, Johnson had suffered a drop in performance. And though skeptics will continue to suspect that Johnson was scared straight after being saved by the tour's confidentiality policy on the use of illegal recreational drugs, he insists the real wake-up call was discovering last year that Paulina was pregnant.

What Johnson has come to learn is that for all his outward cool, he was attracted to partying as relief from internal stress. And although he has never said so, the prospect of fatherhood undoubtedly was profound because it gave him the chance to avoid repeating the same cycle that had affected him.

Golf-wise, the takeaway was that Johnson had become a talented slacker. "I mean, I knew: I'm going to win tournaments; I'm going to be a top-20 player in the world without having to put in much effort. I don't know why, but I have that," he says. "I just got tired of being, you know, just good. I want to be the best player in the world. To do that, I needed to change something."

According to Johnson, the best course was to take a leave. For a few months, he and Paulina lived in a residence near her parents' home in Thousand Oaks, Calif. Along with being adopted by the outgoing family of seven, Johnson played golf with Wayne, the NHL's Great One, nearly every day at Sherwood Country Club. "He's a very cool guy," Johnson says. "I just enjoyed observing him. Just the way he handles himself and deals with people. We talk some, but mostly just hang out together. He can be funny. Like if he makes a long putt, he'll say, 'Hey, you've got to earn your nickname.' "

"Dustin's much more at ease in his life and more calm on the course," Gretzky says. "As far as his ability, I know I'm biased, but he's special. What [wife] Janet and I constantly remind him is that he's so God-gifted, and that with a strong work ethic, there is no reason he can't be the best.

"I tell athletes to never take the privilege of playing for granted, and to play as long as you can," Gretzky says. "I'm 54 years old, and I have a great life and a great family, but when people ask me if I miss hockey, I say, 'Of course I do.' There's nothing I've done outside of it that replaced playing or being a professional athlete. And I think Dustin understands."

Johnson has backed it up in the gym. He shares his workouts with Austin, 27, a former Division I shooting guard with tenacious drive. "We've competed in everything all our lives, and he never likes to get outdone by little brother," Austin says. "Joey D uses that, but DJ's been so focused this year, I don't think he has to." Says Diovisalvi: "Since we started in October, DJ's had that gear where he always gives an exceptional performance, and even beyond." With what Diovisalvi calls off-the-charts strength and flexibility for his body type, Johnson performs such high-challenge power moves as dead lifts with 275 pounds, sets of 15 pull-ups and single-leg squats. Since returning to his Jupiter, Fla., home in March, Johnson has also begun going on long bike rides in a group that includes neighbors Camilo Villegas and Keegan Bradley.

"That's a small sign but a great sign, because it's hard for Dustin to trust enough to commit to a group," Diovisalvi says. "I understand, because I had a difficult upbringing myself. When you trust someone, it's not just about them treating you right. It's also about being accountable to them. In the past, Dustin avoided that commitment. Now he's making strides. I see a guy who doesn't want to let anyone down. And he's not going to let that baby down."

Indeed, Johnson's suits have stayed in the closet. "I wish I'd never bought them," he says. "Now I hang around with the little man in basketball shorts and a T-shirt." He says parenthood has brought him closer to Paulina. "She's a great mother, and she does understand my life. She grew up seeing how Janet helped Wayne. She never gives me any trouble about practicing or training. That helps me do the work."

Although he's still wary of revealing details, at least Johnson is showing pride in the results. "I don't know, I learned a lot of stuff," he told a gathering of reporters recently. "The golf game is good. The family is good. My son is good. Everything is really good."

He's still doing DJ, but better than ever.

.jpg)