News

The Golf Genius Of Ken Venturi

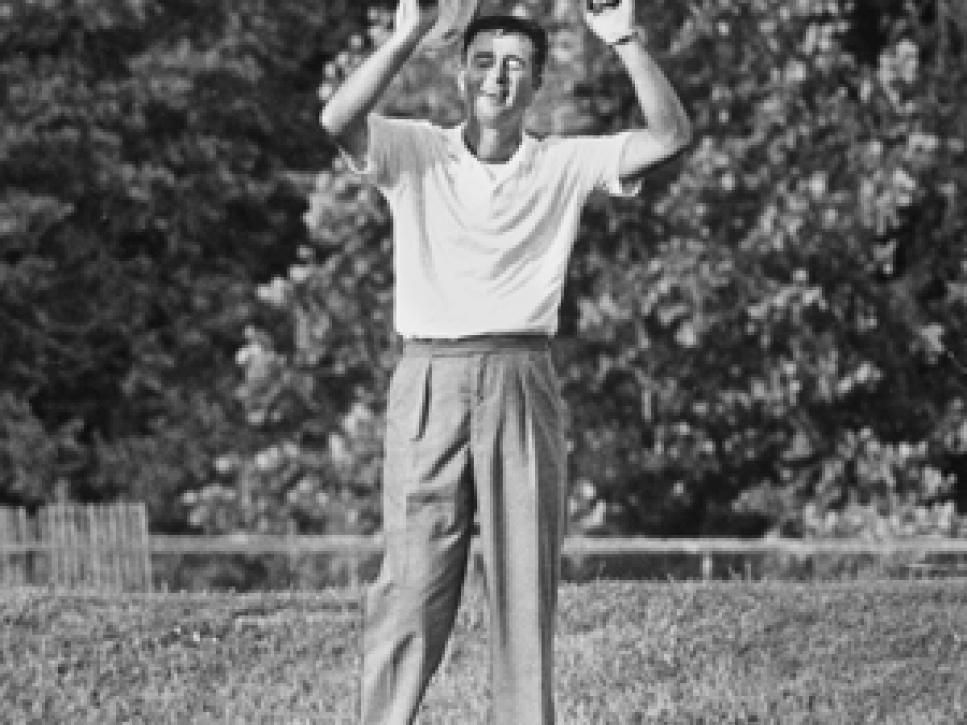

Venturi upon winning the 1964 U.S. Open at Congressoinal.

Monday night was a long-awaited moment for Ken Venturi. At age 81, he was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in the Lifetime Achievement category.

Still, the ceremony in St. Augustine was far from perfect. Because Venturi was recovering from a serious post-operative infection at a hospital near his home in Rancho Mirage, Calif., he couldn't attend to make an acceptance speech.

An emotional man who is even better behind a podium than in front of a camera, Venturi could have been counted on to produce the kind of eightysomething poignancy that -- especially after last year's induction of Peter Alliss and Dan Jenkins -- has become the best part of the Hall of Fame ceremony.

Few had better material than Venturi. Along with his dramatic victory at the 1964 U.S. Open, and coming excruciatingly close in three Masters, he led a golf life of immense dimension. He overcame a childhood stutter by sequestering himself amid the practice holes at San Francisco's Harding Park and slowly talking himself through anticipated glories. He had Byron Nelson as a tutor and Ben Hogan as a mentor, and joined Harvie Ward in playing "The Match" against the two icons at Cypress Point. Two years after being chosen as Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year, he was forced to retire from regular competition because of carpal tunnel syndrome in both hands. As a CBS analyst, most notably partnering with Pat Summerall and later Jim Nantz, he became a welcome weekend guest in living rooms.

But Venturi's most underrated contribution was sharing his understanding of the very highest levels of the game. Though he worked with John Cook from a young age, Venturi quietly helped many great players, including Tom Watson and Tom Weiskopf, whenever asked.

No one has soaked up more Venturi wisdom than instructor Jim McLean, who was an aspiring tour pro out of the University of Houston when the two met through a mutual friend at the 1975 Westchester Classic. "Maybe my curiosity about the swing appealed to him because when I got the nerve to ask him if he would work with me, he said yes," says McLean, who is known to have conferred with more of the game's wise heads than any other top teacher. "It was a life-changing experience."

McLean was soon visiting Venturi at his homes on Marco Island in Florida and Bermuda Dunes in California. Venturi's hands had regained some strength, and the two played countless nine-hole rounds speeding around in Venturi's souped-up cart, detouring to an open hole whenever there was a holdup and often retrieving balls on the green without holing out. It was during these sessions that McLean would see firsthand why Nelson considered Venturi the finest iron player he ever saw.

"Just from a performance perspective, I had never seen such control of the ball," says McLean. "Hitting 14 fairways and 18 greens was not unusual for Ken on those courses. I had studied Hogan, and Ken swung so much like him, with the same quick tempo and that special move where the lower body shifts laterally before the shoulder turn is finished. Like Hogan, he believed the driver off the tee was the easiest shot in the game, and he wanted you to hit that club almost without thinking, which is an advanced concept. With the short game, he was one of those super talented people who could do magic, like calling the number of bounces before the ball bites. Even past his prime, he showed me there was a different level of golf that could be played, and how truly great a player he must have been."

When their rounds decreased as McLean became a full-time teacher with golf schools, he continued to listen and hasn't stopped. "Ken has an incredible eye for the details that matter with the best players," says McLean. "His measure for any sort of swing technique is the test of time. What will stand up when the gun is to your head? It gives him the ability to shine a bright light on the real fundamentals."

McLean, now 62, uses the acquired knowledge to shape his students, including Keegan Bradley and Lexi Thompson. "At the highest level it's a bunch of little things that make the difference, and Ken knows more of those things than anybody," says McLean. "I hope that people will remember him for that."

Perhaps he will be, particularly if Venturi -- as the Hall of Fame hopes -- can deliver his acceptance speech in person at next year's induction. If so, though it won't be as long awaited as this year's moment, it will be an even better one.

.jpg)