News

U.S. Open 2020: In trying to match Francis Ouimet's feat, Matthew Wolff is chasing a true legend

Francis Ouimet (center) poses with Ted Ray and Harry Vardon at the 1913 U.S. Open. (Associated Press file photo)

It was exactly 107 years ago today—Sept. 20, 1913. Francis Ouimet, a 20-year-old amateur golfer and former caddie at Brookline Country Club in Massachusetts, shocked the sporting world with his playoff victory in the 19th U.S. Open—the first national championship Ouimet had played. Over the extra 18 holes on a Saturday, Ouimet whipped by five strokes a pair of renowned Britons, Ted Ray and Harry Vardon.

Today, at another historic venue, Winged Foot Golf Club in Mamaroneck, N.Y., 21-year-old Matthew Wolff—the 54-hole leader—has a chance to match Ouimet’s feat. In the 110 editions of the U.S. Open since Ouimet’s triumph, no first-timer has ever prevailed.

With that history in the balance on Sunday, we offer this examination of Ouimet and his triumph, as told in fine detail by former Golf Digest staff writer Bill Fields in 2013, on the feat’s 100th anniversary.

- • •

He had been a caddie and a student, but by 1913 Francis Ouimet was something other than a sporting-goods salesman at Wright & Ditson in Boston. See for yourself, in the pages of the Brookline (Mass.) directory. Among the town’s residents—teachers and carpenters, widows and blacksmiths, dentists and horsemen—was a listing for a family at 246 Clyde Street, across the road from The Country Club.

Ouimet Arthur gardener Clyde Country Club

Francis golfer Clyde Country Club

That September, when the U.S. Open was held at The Country Club, British stars Ted Ray and Harry Vardon and the rest of the world would find out just what kind of golfer the 20-year-old son of Arthur Ouimet really was.

John G. Anderson, a Boston golfer and golf writer already knew. Several years earlier he had witnessed Ouimet’s golf skills in a match between Brookline High and the Fessenden School, where Anderson taught. En route to winning the 1913 Massachusetts Amateur, Ouimet went 2-3-3-3-3 to beat Anderson, 3 and 1, in the semifinals. “If there ever was a born golfer,” Anderson wrote during Open week, “it is this boy.”

No matter that Ouimet’s first golf was played on makeshift holes in the pasture behind the family home with older brother Wilfred, that his first golf balls were ones members at The Country Club had misfired, that his father discouraged his pursuit of the game or that his early forays to play a real golf course, Boston’s public Franklin Park, were four-hour round trips on foot and by streetcar.

“Sometimes,” Ouimet said years later, “I believe the real satisfaction comes from the struggle, not the reward.”

That was a template for his striving, for every underdog who would follow, for an America that, in 1913, was still trying to prove it had the chops for this new game from the old country. But what occurred that monumental week would shape a century as the United States ascended into a golf power, eventually usurping the land that exported it across the Atlantic. Dreamers beget dreamers—from Ouimet to Gene Sarazen, Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones to Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson and Sam Snead, on to Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Tom Watson and Tiger Woods.

First, though, there had to be a spark to ignite the flame.

“The result is impressive almost beyond belief,” The (Brookline) Townsman wrote of a silent motion picture, “Les Misérables,” playing at the Tremont Temple, in its Sept. 20, 1913 edition.

An outdoor performance that day would merit the same review.

The man who invented golf writing, Bernard Darwin, who would chronicle the U.S. Open for The Times of London, wondered before a shot was struck “whether Americans have a national genius for doing things young.” Certainly the U.S. Open champion of 1911 and 1912, professional Johnny McDermott, the first American-born winner of the national championship, had been a testament to the prowess of youth and how golf was catching on in America having won both his titles before his 21st birthday.

“If this country is to maintain her position at golf,” Darwin, an Englishman, wrote, “her leading players, both amateur and professional, will certainly be ill-advised to think that there is nothing to be learned from the players in the United States.”

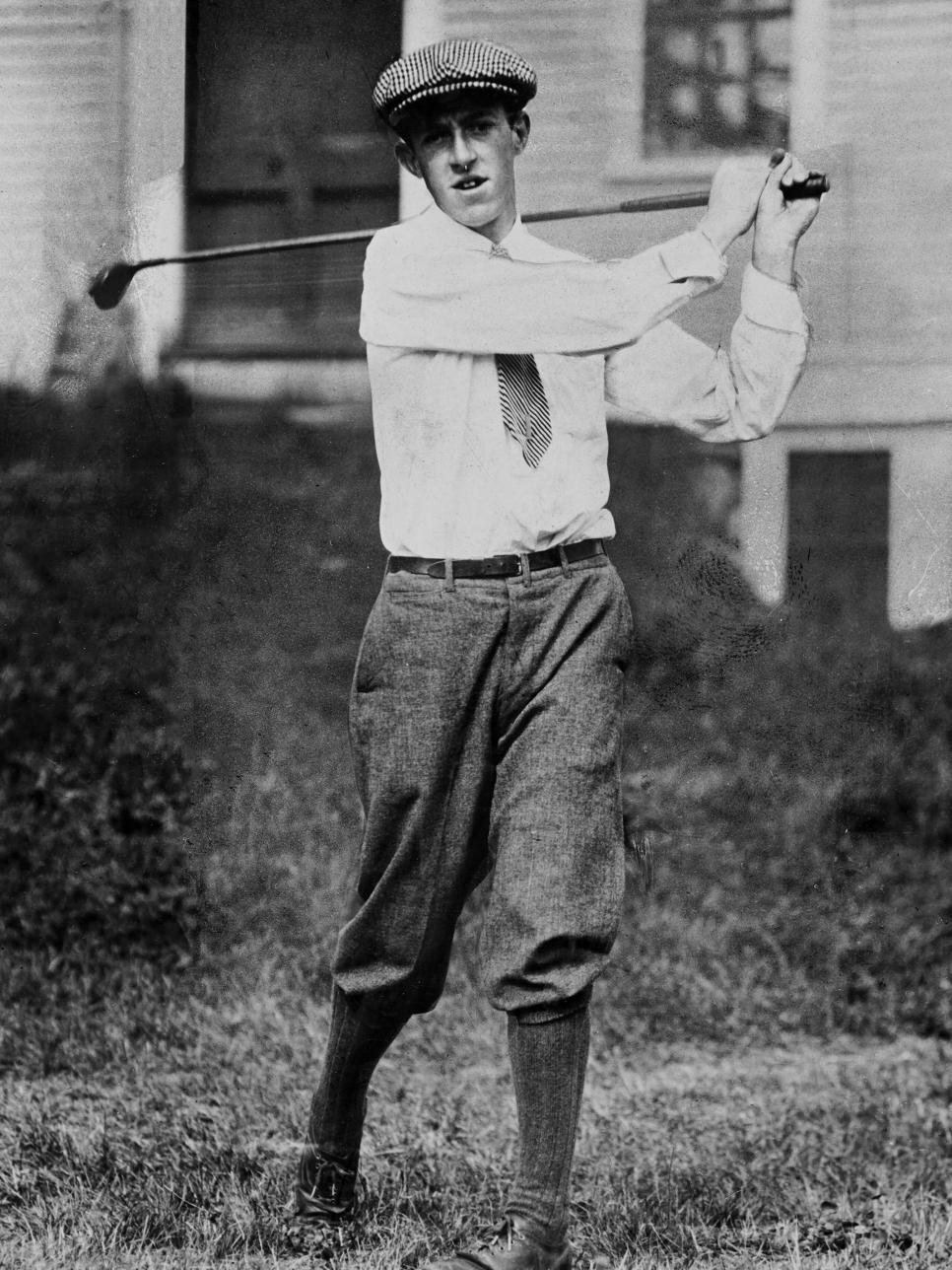

Francis Ouimet was observed to have a dynamic and powerful swing. (Photo by PGA of America via Getty Images)

PGA of America

Yet McDermott’s national titles had come without having to defeat Vardon, by now a five-time British Open champion and the finest stylist golf had seen, or Ray, a burly, long-hitting talent who won the 1912 British Open prior to his 1913 sojourn with Vardon to the U.S. There the two titans would play many exhibition matches before and after the Open—which had been shifted to the fall to accommodate their barnstorming.

Despite his respect for American golfers, Darwin, filing a story from Brookline two days before the first round of the U.S. Open, figured McDermott as the lone threat to deny the two British stars. “I confess that I cannot in my mind’s eye see any man in this field, save only McDermott, beating Ray or Vardon over four rounds,” he wrote. “McDermott is, of course, a really fine player and is perfectly capable of winning. I may be wrong as to the others, but at present I shall stick to my opinion.”

Even though he struggled to a pair of 88s practicing at Wellesley C.C. Sept. 14, Ouimet, one of a record 162 entrants, qualified easily for the 66-man field with a 36-hole score of 152. Ouimet had a dynamic and powerful full swing—at least once he outdrove (Long) Jim Barnes during qualifying—and owned valuable local knowledge of The Country Club from his many caddieing loops and surreptitious shots that sometimes led him to being shooed away from where he didn’t belong.

The Open was Sept. 18-19, 36 holes a day over the 6,245-yard course. Far from playing as if he were out of his element in the first round, Ouimet—with pint-sized 10-year-old Eddie Lowery as his caddie—shot a 77, T-17 and six behind the 71s of Macdonald Smith and Alex Ross but safely sandwiched between favorites Vardon (75) and Ray (79). In the second round the American amateur and the British pros all improved, Vardon assuming a second-round tie with Wilfrid Reid at 147. Ray’s 70 took him to T-3 at 149. Ouimet’s 74 had him within striking distance at 151.

Reid and Ray got into a fight that night at dinner about the British taxation system, Ray drawing blood when he punched his smaller countryman twice in the face. Reid disappeared from contention the next day with rounds of 85-86. In dreadfully wet conditions, Vardon and Ray, in different groups finishing more than 90 minutes ahead of Ouimet, shot 78-79 and 76-79 to finish 72 holes at 304.

Ouimet’s 74 was the second-best score of the third round, allowing him to share the 54-hole lead with Vardon and Ray. After dubbing his tee shot on the 140-yard 10th hole during the fourth round and making a double bogey, however, Ouimet faced a steep climb and needed to play the last six holes in two under to get into a playoff.

He chipped in for a birdie 3 from a difficult position on the 13th. Pars on the next three holes meant he still needed to birdie one of the last two to tie. After using his jigger (a 4-iron equivalent) to hit his second shot on the par-4 17th to 15 feet, Ouimet’s bold putt, traveling on turf he knew from dawn and dusk sneak-ons, rattled the back of the cup for a vital 3. A chip-and-putt par at 18 gave him a closing 79 and an appointment with destiny.

“Whoever wins,” Darwin wrote, concluding his dispatch after Ouimet’s fourth-round rally to tie Vardon and Ray, “there is only one hero of this Championship, and that one is Mr. Ouimet.”

Ouimet wouldn’t let Lowery (whose name was widely misreported as “Laurie” in the newspapers) be bullied off his bag by more seasoned hands prior to the start of the playoff. The little fellow urged on Ouimet with a patriotic message before the extra 18 began. “You’ve just got to beat those fellows, Francis,” Lowery told him. “They never can take the championship across the water with them.”

During the U.S. Open, Francis Ouimet walks with his 10-year-old caddie Eddie Lowery. (Associated Press file photo)

The day again started gloomy and damp, a mist hovering over the The Country Club’s topography, which Darwin described as “rolling meadow land, thickly and prettily wooded, with every now and then a formidable rock that adds a touch of wildness and romance.”

There would be more than moisture in the air. “Golf is an uncertain game in which breaks can and often do play a large part,” Ouimet later observed. He got two really good ones—beyond having the puckishly encouraging Lowery for a sideman—in the playoff.

On the 420-yard, par-4 fifth hole, Ouimet’s hands slipped off the rain-slickened grip of his brassie on his second shot. His ball flew sharply to the right and out of bounds, then a distance-only penalty. “Ouimet was lucky; if the ball had remained in play among the trees and underbrush, he might have made any score,” wrote Robert Sommers in The U.S. Open: Golf’s Ultimate Challenge, describing the moment. “Still calm, he dropped another ball, played a wonderful shot onto the edge of the green, and made his 5, matching Vardon and Ray.”

Five holes later, at the short 10th that had been so costly to him in the fourth round, still tied with Vardon and Ray, he hit the green and two-putted for par. The Brits, though, fell behind Ouimet after they were left in a predicament after their tee shots. “This green was so soggy,” Ouimet wrote in A Game of Golf, “that both Vardon and Ray, after pitching on, had to chip over the holes made by their balls as they bit into the soft turf and hopped back.”

The bogeys by the Brits gave Ouimet a lead he did not relinquish. Heeding the advice McDermott had offered him as he warmed up before the playoff, Ouimet wasn’t worrying what his highly favored opponents were doing. “… I did not wish to be unduly influenced by anything they did,” was Ouimet’s description of his mindset. “I was simply carrying out McDermott’s instructions and playing my own game.” As a modern sport psychologist would term it, Ouimet was into the process, staying in the present. Had there been scoreboards, he likely would have resisted sneaking a peek.

“I was fearful at the beginning that I should blow up,” Ouimet would write, “and I fought against this for all I was worth. The thought of winning never entered my head, and for that reason I was immune to emotions of any sort.”

Ray’s form presently left him, and he trailed Ouimet by five after 16 holes. Vardon, however, was still a threat, only one behind as the threesome got to the 17th, which treated Ouimet so sweetly in the fourth round. But the best golfer the world had known—so accurate it was said in afternoon rounds his tee shots would find fairway divots he had taken that morning—succumbed to the moment as well.

“The pressure on them and myself was entirely different,” Ouimet told Life magazine in 1963. “Their prestige was at stake. It had finally dawned on them how terrible it would be if I beat them.”

Vardon took a bold line up the left so he would have a shorter approach, but his tee shot didn’t carry far enough, finishing in a bunker near the lip, a lie that forced him to play safely to the fairway. A Vardon bogey to Ouimet’s second birdie in a row on the hole adjacent to the young man’s home meant breathing room for the finale. It was all over but more shouting from the damp, deliriously happy gallery. Ouimet’s routine par 4 gave him an even-par 72 to Vardon’s 77 and Ray’s 78.

Darwin’s pre-championship prognostication had been wrong, but he heaped praise upon the surprise winner, who had only played better as the pressure increased. “I think today’s achievement was finer still,” Darwin reported after the playoff. “He had had a night to sleep on the situation in which he suddenly found himself. He had to play against Vardon and Ray actually in the flesh, not merely against their scores on paper. He had to see their shots and follow them. He was one David against two Goliaths, and moreover, it was not that Ray and Vardon played badly.”

Fifty years later in USGA’s Golf Journal, Reid appraised the unlikely but popular champion. “Here were poise and grace,” Reid remembered. “He had charm and flexibility seldom seen. What he lacked in knowledge of golf strokes was overcome by his ability to control and command himself.”

At the triumphant conclusion of the Open, no one could control the scene. The crowd, thousands strong, which stewards had attempted to contain with ropes, flags and orders shouted through megaphones, stormed the 18th green after the upset was complete.

“A roar went up which shook the air and rumbled away for miles,” the New York Tribune reported. “Thousands of dripping, rubber-coated spectators massed about Ouimet, who quickly was hoisted to the shoulder of those nearest him while cheer after cheer rang out. Excited women tore bunches of flowers from their bodices and hurled them at the youthful winner, hundreds of men strove to reach him in order to pat him on the back or shake his hand.”

Amid the throng was Ouimet’s mother, Mary, who after managing to get a word of congratulations to her son, made the short but muddy walk home. Ouimet, Vardon and Ray changed into dry clothes before the trophy ceremony. A hat was passed for Lowery, into which a reported $150 was collected. Ouimet celebrated with a “Horse’s Neck,” a blend of ginger ale and lemon juice and went out to eat and see a show with a friend that evening.

The vanquished were gracious in defeat. “Mr. Ray and I didn’t have a chance to win the championship,” Vardon said. “Mr. Ouimet played the most wonderful golf I ever witnessed, and not once did he leave an opening for me to gain in and I was simply trailing along the links with your hero. I do not think I will live long enough to see better golf.”

Ray: “I have no hesitation in saying that he played better golf the whole [three] days than any of us.”

In a lengthy bylined story in the Sept. 21 Boston Sunday Globe, Ouimet’s inherent modesty briefly left him. “[On] the whole I fail to see where our English cousins have very much to teach us, if I may be pardoned in making the statement,” he said. “Today, for instance, Ray did not outdrive me to any great extent, and I think I held my own with Vardon in this department. Their midiron and mashie shots are well executed, but what they gained on these they lost on the greens.”

Ouimet’s achievement, as writer Herbert Warren Wind described it in his 1948 book The Story of American Golf, was a “wholesale therapeutic for American golf,” something whose ingredients stirred the country’s imagination for the sport, creating more courses and more golfers (nearly a six-fold increase in the latter, to two million, by 1923).

In its Sept. 27 edition, The Chronicle of Brookline wrote: “While we admire his skill in the game, we think the town in particular to be proud of the sand and nerve he showed in his contest with the two great English players. Not merely as a golfer, but as a man, Ouimet has qualities that promise to be the making of an unusual career.”

Francis Ouimet holds the U.S. Amateur Championship trophy after winning the title in 1931 in Chicago.

Bettmann

As a man, years later, Ouimet gave the boys who caddied for him a dollar when custom was a third of that. He used a simple, lightweight canvas golf bag, on which he collected autographs of the thousand or so lads who looped for him. He died in 1967 at 74. Upon his death, Arthur Daley of The New York Times wrote: “If he had been old or rich or a British pro, his victory would have supplied no impact.” But that wasn’t who Ouimet had been. He had been young, of modest means, an American underdog rising to the occasion, the first of only five amateurs to win the U.S. Open.

USGA president Robert Watson hadn’t been in Brookline for the playoff. He found out what happened in a phone call. “It’s the most wonderful thing that ever happened in the history of golf,” Watson said.

A century later, still impressive almost beyond belief, it arguably remains so.

• • •

MORE U.S. OPEN 2020 PREVIEW CONTENT FROM GOLF DIGEST: Every Hole at Winged Foot: Exclusive drone footage | 13 best bets for the 2020 U.S. Open | Ranking the top 100 players in the field at the 2020 U.S. Open | 8 interesting revelations about the epic 2006 Open at Winged Foot | The ‘other’ miscues that cost Phil Mickelson the 2006 U.S. Open | Interactive guide to New York’s great golf courses | A super-scientific ranking of Winged Foot’s 11 previous major championships | 7 shots that can make or break any round at Winged Foot | At Winged Foot, a pandemic stirs memories of the last time the world stopped | The Winged Foot mystique | The 15 best U.S. Opens, ranked