News

Real Secrets of Golf Course Architects

With all due respect to Michael Patrick Shiels and the members of the American Society of Golf Course Architects, their new, colorful, hefty coffee table book, Secrets of the Great Golf Course Architects (Skyhorse Publishing, 2008), is entertaining but not revealing. There are no genuine secrets within its pages, unless it's that golf architects routinely encounter wild animals during site visits.

True secrets are messy, embarrassing, sometimes even shameful. That's why golf architects, who often swap inside stories among themselves, won't discuss them publicly.

But we will.

Animal House

Long Cove Club on Hilton Head Island is a cherished Pete Dye design, No. 78 on Golf Digest's America's 100 Greatest Golf Courses. If its well-heeled membership knew what went on behind the scenes during the course's creation, they'd fall out of their carts.

One eyewitness described the process as "Animal House-builds-a-golf-course." The 1980-81 crew was mostly young turf students, good golfers who knew nothing about operating equipment. That's how Pete wanted it. He didn't want experienced workers who would build him a conventional course. Pete hired Bobby Weed, assistant superintendent at Amelia Island, to serve as project supervisor. Weed recruited interns from his alma mater, Lake City (Fla.) Community College, including Ron Farris, Scott Pool and David Savic. Pete assigned his younger son, P.B., to work as a bulldozer operator and told Weed to hire another young kid who had been penciling him to death for a job. "Put him to work picking up sticks all summer," Pete said.

That kid was Tom Doak, a Cornell University student "so skinny he could barely pick up a rake." Doak kept wanting to show everyone his slides of golf holes. The gang finally consented one evening during a beer bash; his slides of Cypress Point, Pine Valley, Merion and others quieted the crowd. "After that, we gave him some slack," says Farris.

The crew worked -- and played -- hard. Beer and other delights flowed freely most evenings, and sometimes during the day.

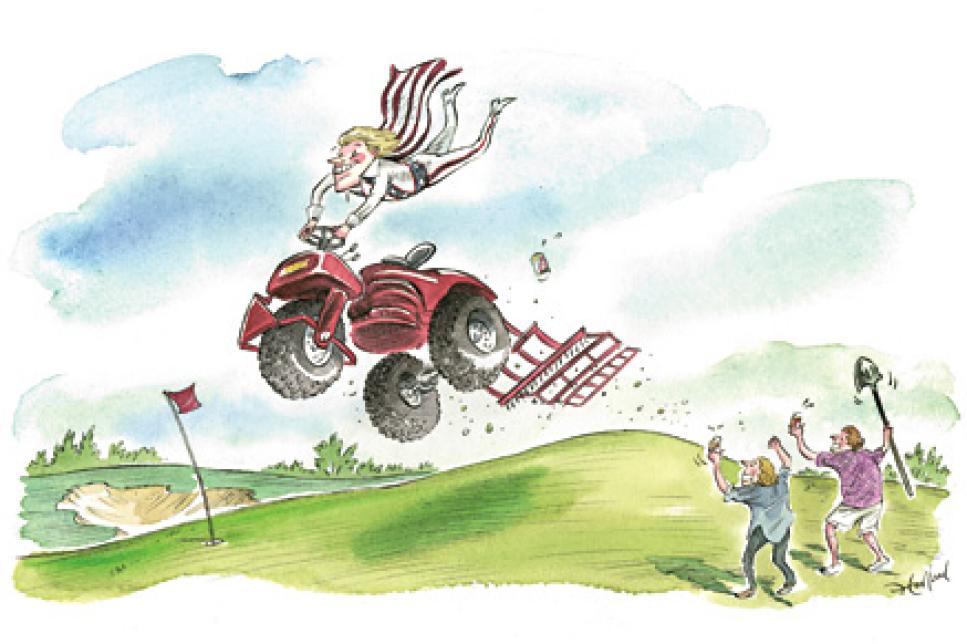

P.B. was the Belushi character, a wild man who cleared several fairways by chasing kids through the forest with his bulldozer, bursting out of tree lines at full throttle. Others had "dune buggy races" on "sand pros," the small but powerful three-wheeled motorized tractor-rakes used to float out green contours. One "Evel Knievel" contest to see who could sail a sand pro the farthest through the air led to the final shape of Long Cove's notorious eighth green, with its back shelf (the launch) nine feet higher than its lower level.

From those antics emerged a great golf course -- and a new generation of golf architects. Weed has since designed TPC River Highlands in Connecticut, Spanish Oaks in Texas and Olde Farm in Virginia among others. P.B. Dye has done a bunch, too, including Black Bear in Florida and Ruffled Feathers in Illinois. Farris did The GC at Red Rock in South Dakota, Pool did Mountain Air in North Carolina and Waterfall in Georgia, and Savic designed College Fields in Michigan and NorthStar in Ohio (with John Cook). Doak is the most famous of all, with Pacific Dunes in Oregon, Ballyneal in Colorado, Cape Kidnappers in New Zealand and Barnbougle Dunes in Australia.

Of all their achievements, Scott Pool stands out, because he is the only golf architect ever to win an Emmy, in 2008. You know that "AimPoint" putting line they use on Golf Channel broadcasts to indicate the correct line to the hole? Pool helped invent and develop it.

Crime Beat

At least two golf architects have ended up in the slammer.

After he emigrated from England in 1890, Albert Rolls became one of America's pioneering course designers. He staked out courses in Chevy Chase and Annapolis, Md., then moved to the Midwest where he laid out the original Omaha CC and St. Joseph (Mo.) CC.

He retired in the late 1920s to a home in St. Joseph, sharing it with a son who had been severely injured during World War I. One evening in July 1939, Rolls, then 70, inexplicably shot his son's nurse with a shotgun, then turned the gun on himself. Both the nurse and Rolls survived their wounds, and Rolls was charged with assault with intent to kill. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to two years in prison. When he died in 1950, his obituary said he spent his last years as a master mechanic in a machine shop. It's unclear whether that was simply a euphemism for stamping out license plates.

Ted McAnlis, a one-time NASA civil engineer, learned golf design by working for architects George and Tom Fazio in Florida in the early 1970s. He then spent nearly 30 years designing courses on his own, doing some of the most beautiful, playable tracks in Florida, including St. Andrews in Boca Raton, Sherman Hills in Brooksville, Waterlefe in Bradenton, River Wilderness in Parrish and Venice G&CC.

He was good and made a lot of money, all of which he apparently wanted to keep. In 2002 McAnlis was indicted for not filing a federal income-tax return since 1977. In a 2003 trial, prosecutors produced evidence that he had willfully evaded taxes of more than $1.3 million (including penalties and interest) by establishing a sham church, using false social-security numbers and placing assets in a Bahamas bank. He was convicted by a jury of tax evasion and is now serving 10 years in federal prison.

[Ljava.lang.String;@d6c51c7

Grand Old Competitors

We tend to view the Golden Age architects as genteel, civil gentlemen who were in it for the love of the game. Turns out, those guys were just as petty and competitive as modern-day architects.

Consider this portion of a 1923 letter written by Donald Ross, explaining to a friend why he wouldn't take a job redesigning Dedham (Mass.) Polo & CC:

"The story is this. The first nine holes they had was laid out by myself on very restricted land and a shortage of money, but it worked out very well indeed. When Herbert Fowler, the would-be architect, came over to America, the club was better able to build a real course, and instead of giving me a chance they hired him and it was published in all the Boston papers that Fowler was the world's greatest expert. His work proved to be an absolute failure, not only at Dedham but also on every other job where he worked. Now they want me to take up where he left off and if I succeed in doing anything with it, Fowler, and not I, will get the credit. I have had this experience before … [If] I did the Dedham work it would mean a sacrifice on my part which I am not willing to make."

Or A.W. Tillinghast's 1935 review of Durand Eastman GC in Rochester, N.Y., a new municipal layout by then-young, unknown Robert Trent Jones: "Several of the greens are so grotesque in their conception that already the authorities recognize the necessity for complete reconstruction, notably the 5th and 6th greens, and I gave them considerable advice concerning new plans and construction methods. My investigation of this course was particularly thorough, for their problems are many."

Designer Labels

Every club wants to believe it has a Rembrandt.

Mayfair CC in Sanford, Fla., insists its course was designed by Donald Ross. It wasn't. The course was designed in the early 1920s by Cuthbert Butchart, a longtime club pro from Westchester CC in Rye, N.Y.

We think the confusion occurred back in the 1950s, when the course was renamed Seminole and sold to the owner of the New York Giants baseball team. When the Giants left for San Francisco, the course was sold again, and the new owner started advertising that he had a Donald Ross design. Ross did design a Seminole, but it's farther south in Juno Beach. We've played that Seminole. We've played Mayfair. Mayfair is no Seminole.

We were all fooled about Hyde Park GC in Jacksonville, figuring it was a Ross creation because PGA Tour pros Chris Blocker and Billy Maxwell said it was when they bought the course in the 1970s. The Donald Ross Society even had an outing there in late 1994 and praised the design.

But if you check the Jacksonville Journal for Dec. 2, 1926, the day the course opened, you'll find Hyde Park was designed by "famous Canadian architect Stanley Thompson." The American Golfer magazine of same month confirms that. A 1948 Saturday Evening Post feature on Thompson also lists Hyde Park as among his designs.

Why the confusion? Well, there are blueprints for a Hyde Park among the Ross papers in the Tufts Archives in Pinehurst, N.C., but those plans are for Hyde Park G&CC in Cincinnati. And Ross once advertised Jacksonville Municipal among his designs, and for a time, Hyde Park was one of Jacksonville's municipal layouts. But Ross' Jacksonville Municipal was Brentwood GC, which closed in the 1970s.

Past President To Present Phenom

Here's our Six-Degrees-of-Kevin-Bacon way to link former President Richard M. Nixon to Tiger Woods:

As we know from the current film, Nixon was interviewed after his resignation by British TV commentator David Frost … Frost's first TV show in America was a prime-time weekly called "That Was The Week That Was" … Another regular on TW3 was singer Nancy Ames … Ames was once married to golf architect Jay Riviere … Riviere previously had been an assistant pro to Claude Harmon at Winged Foot GC … Claude's oldest son is a premier golf instructor Butch Harmon … Butch helped Woods retool his game a few years after Tiger turned professional.

Fish Story

Every architect has at least one tale about the big one that got away. For the team of Mike Hurdzan and Dana Fry, it was White Tail near Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. Situated on a graceful, pine-dotted plateau, their routing featured lots of panoramic views of Lake Coeur d'Alene 350 feet below.

But years of delays caused by environmental permitting and legal actions took their toll on the developer. Discovery Land Co. acquired the property, and its chairman, Michael Meldman, brought in his favorite architect, Tom Fazio.

Fazio's West Coast associates, Dennis Wise and Scott Hoffman, ignored most of the Hurdzan-Fry routing, reversed one stretch of holes and went off in another direction at another point. They provided Discovery with a winner, Gozzer Ranch, Golf Digest's Best New Private Course of 2008.

Hurdzan and Fry were disappointed they didn't get to build the course they had envisioned, but couldn't complain much, because Discovery Land paid them the full design fee of their original contract.

[Ljava.lang.String;@79f0e800

The most disappointed guy has to be golf writer Jonathan Cummings, who had followed the project from the beginning. Hurdzan had promised Cummings he would get to design and build one hole at White Tail entirely on his own.

Not Universally Loved

Furman Bisher's The Masters: Augusta Revisited, An Intimate View (1976) reveals a particularly candid take on a legendary architect by 1935 champion Gene Sarazen: "I wasn't too impressed with Augusta National. Of course, I was never a great admirer of Dr. Alister MacKenzie's architecture. I'd seen several of his courses in Europe. He had more freakish greens than anybody I'd ever seen. Even Colonel Jones, Bob's father, used to complain about it."

Eavesdropping

Ever wonder what really went on between Jack Nicklaus and Tom Doak during their collaborative design at Sebonack GC on Long Island?

Here's a bit of their discussion, overheard as they walked the par-5 13th, the last hole to be constructed because it served as the staging area for piles of sand and pipe. They started at the back tee, and Jack was annoyed by a prominent mound some 40 yards in front of it.

Jack: "Why leave that knob? The only criticism it'll get will be from good players who can't see the fairway."

Tom: "My thing is visual. All you see is green grass. The knob makes it visual. It pulls the green toward us. It plants the idea of going for it."

Jack: "In the mind of a scratch player or an 11-handicapper? You've said a bunch of stuff that a scratch player would never think."

Tom: "Well, a low-handicapper. If the green looks close to him, he'll overswing and get into trouble."

Jack: "All this stuff over one little pile of dirt. Look, it's my tee back here and if I want to get rid of it, I'll get rid of it."

They move down the fairway, where a plastic-lined, environmentally dictated retention pond was installed at the base of a hill below the proposed green. Both agree the pond looks too artificial.

Jack: "What if you built a waste bunker along the edge of the lake, break up that linear look?"

Tom: "I don't want to put a waste bunker against water. That looks like a hundred other modern golf courses. That's what I really don't want to do."

Jack: "You really don't like it?"

Tom: "I like to let human nature work against golfers sometimes. Why bunker right up to the water and dictate their shot? If they're silly enough to hug the lake on their second shot, then it's their fault if they go in."

Jack: "But we have to take up the elevation somehow. There had been a cliff between the pond and the fairway. Another option is to put that cliff back."

Tom thinks about it for a minute, then shakes his head.

Jack: "OK, let me throw out another idea for you to reject."

After another visit, the two reached a compromise, and the hole was finally completed, 550 yards from the tips, with only a slight rise in front of the back tee and a couple of rugged bunkers recessed into a slope edging the water hazard.

Their brainstorming was worth it. Golf Digest named Sebonack, which will host the 2013 U.S. Women's Open, the best new private course in 2007.

Look But Don't Touch

Clubs intending to host a U.S. Open remodel their courses three, five, even nine years before the event. But it wasn't always that way.

Colonial CC in Fort Worth was only four years old in May 1940 when the USGA announced it would host the U.S. Open the very next year. Although proud of his course, owner Marvin Leonard wanted it tougher, so he rushed in architect Perry Maxwell to create three new holes and rebunker the rest. Maxwell's associate (and former brother-in-law) Dean Woods took charge in June and spent the remainder of the year carving out new fourth and fifth holes from a 10-acre walnut thicket, building a new par-3 13th over a bend of the Trinity River and adding 56 bunkers to other holes.

Word spread in the spring of 1941 about the revamped course, particularly the "Valley of Sin" 469-yard par-4 fifth, with a fairway "skinny as a dachshund" squeezed between a gulley and the river. But when players arrived June 2 to begin practice rounds, they were told the fifth hole was off limits. Heavy rains in late April had washed away most of its fairway. Although it had been resodded, the hole was still roped off and hadn't been mowed. Players had to skip the hole on Monday, and finally got to play it for the first time on Tuesday, two days before the Open began.

The fifth proved to be both ragged and rugged. Winner Craig Wood bogeyed it all four rounds, posted four-over 284 and won by three.

Two postscripts: The big headline on the eve of the 1941 Open (besides the death of Lou Gehrig) was the announcement that the USGA was placing a limit on the distance a golf ball could be driven. Those were the days, critics would say, when the USGA still controlled equipment.

And Colonial, now the oldest continuous host of a PGA Tour event, was totally remodeled (again) last summer by architect Keith Foster, a rare breed who downsized years ago by dismissing most of his staff, moving his office into his home and accepting only a few select remodeling projects each year, such as Baltimore CC, Omaha CC and Colonial. This winter, while many of his competitors are spanning the globe in search of work, Foster is in Africa, achieving a personal goal. He's climbing Mount Kilimanjaro.

Teamwork

Back in the late 1960s, the USGA seriously considered building its own tournament course in New Jersey, jointly designed by the three most prominent names of the day: Robert Trent Jones, George Fazio and Pete Dye.

Sadly, the project fizzled, so we will never know if those three would have produced a camel or a thoroughbred. But the land the USGA targeted for its project is today a golf course, done independently of the governing body. It's New Jersey National in Basking Ridge, just a few miles from Golf House. The course designer was Roy Case, a transplanted Englishman.

In the early-1990s, Robert Trent Jones Jr. proposed a one-of-a-kind design by himself, his father and his brother in Orlando. But brother Rees, who already was working on a design just three miles away, declined, saying he would not participate in anything that would compete against his own client. His course is Falcon Fire. Just to the south of it is the senior-junior design, Celebration GC.