News

Troubled Genius

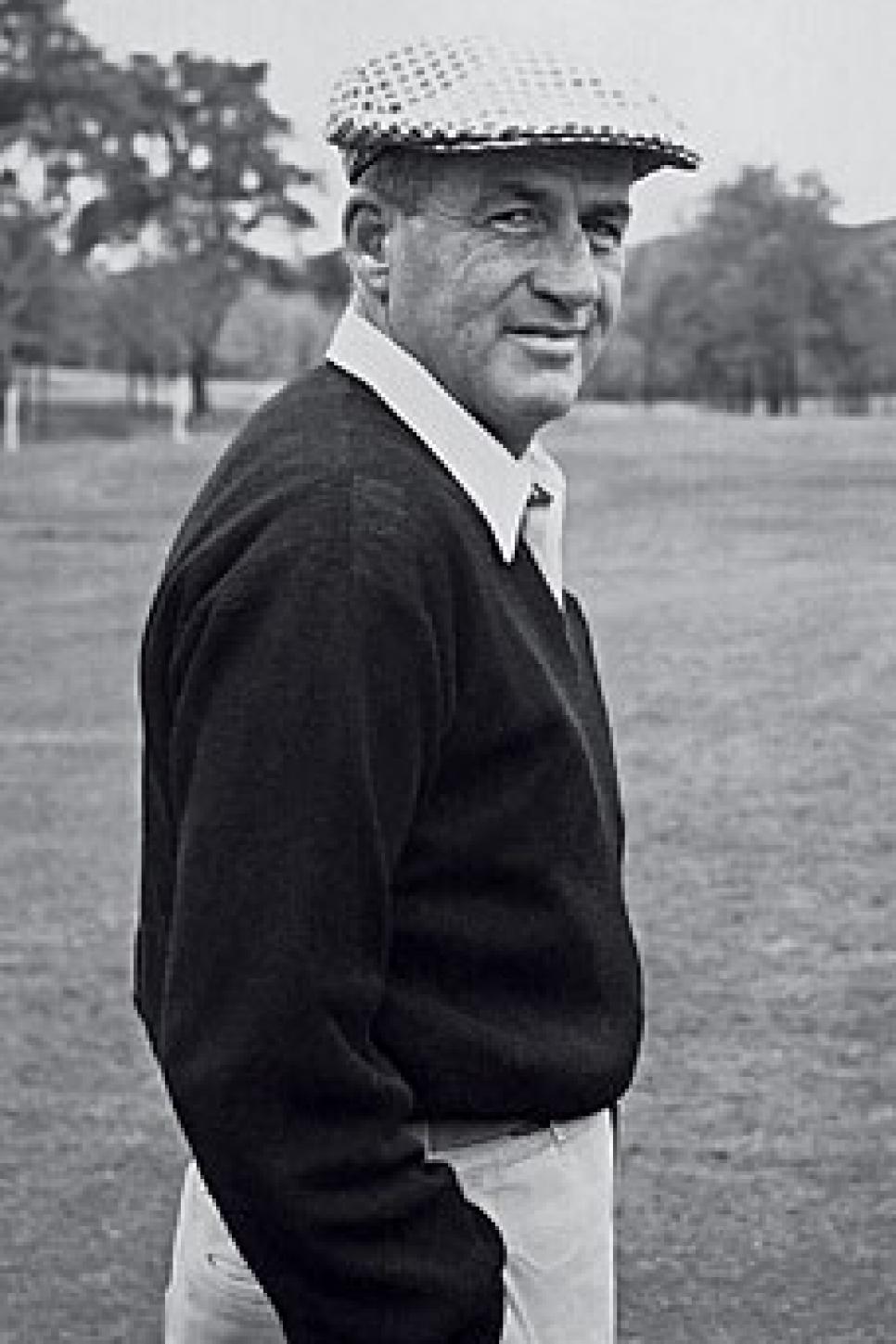

Public Favorite: Wilson designed 74 golf courses, including Cog Hill No. 4, which was recently updated by Rees Jones.

When Joe Jemsek hired Dick Wilson to design a championship-caliber course at his Cog Hill facility in Lemont, Ill., in the early 1960s, Wilson rivaled Robert Trent Jones as the best architect in golf. Oddly, though, Wilson didn't have the run of the place when he made site visits to create Jemsek's vision of a public layout to stand up to nearby Medinah No. 3.

"Dick told [design partner] Joe Lee, 'That's the most exclusive damned clubhouse I've ever seen in my life,' " Jemsek's son Frank recalls. "Dick complained, 'They won't ever let me in the clubhouse.' "

Joe Jemsek was a man of the people if there ever was one, his doors open to all. He also knew, however, Wilson was in the midst of a losing battle with alcoholism. "My father didn't want him to have any alcohol," Frank Jemsek says. "My father knew he would start drinking if he went in the clubhouse and the day would be over by noon. They bought him lunch out on the golf course."

Brawny and beautiful Cog Hill No. 4, also known as "Dubsdread," is a testament to Wilson's skill as an architect, but Jemsek's clubhouse ban typifies how dramatically Wilson's drinking affected him, particularly near the end of his career. "It was a love-hate relationship with Dick, with intensity of both feelings," says architect Robert von Hagge, a long-time associate who worked on 40 courses with Wilson. "He was a true Jekyll and Hyde."

More than four decades after his death at age 61 in 1965, Wilson is back in the spotlight. Cog Hill No. 4 will re-open this spring after a renovation by Rees Jones, one of Robert Trent Jones' two sons. Regarded by many as an everyman's gem—it was No. 29 on Golf Digest's 2007-08 ranking of America's 100 Greatest Public Golf Courses—the longtime home of the Western Open will host the BMW Championship as part of the FedEx Cup Playoffs this September. Joe Jemsek had a life-long dream of having a U.S. Open on Dubs, and Jones believes his update of Wilson's layout, where Tiger Woods has won four times, could make it Open worthy.

If Cog Hill—lengthened to more than 7,600 yards and boasting Jones-revamped greens, which now feature a SubAir drainage system—lands the national championship, it will be a fitting tribute to Wilson, whose 74 designs include some of the game's best-known courses. He did Doral's Blue Monster, Royal Montreal, Pine Tree, Laurel Valley, PGA National and Moon Valley in Phoenix, site of Annika Sorenstam's memorable LPGA record 59 in 2001.

The son of a contractor, Wilson grew up in Philadelphia and got an early taste for the business as a water boy during the construction of Merion GC. A fine athlete who attended the University of Vermont on a football scholarship, he joined the design team of Bill Flynn and Howard Toomey after college. Wilson became a construction superintendent with Toomey and Flynn, and oversaw the implementation of Flynn's design at Shinnecock Hills in 1931. The Depression impacted the design business and Wilson was forced to take a job as a pro/greenkeeper at Delray Beach (Fla.) CC.

After serving in World War II, where he constructed and camouflaged airfields, Wilson formed a design company and added Lee as his partner in the 1950s. The pair collaborated on many projects—Lee was the safe and conservative voice, Wilson innovative and daring, according to von Hagge. "He always preached to stay within the history and tradition of the game, but push it out as far as you can," von Hagge says. "He was doing stuff that hadn't been seen before. He loved bold expression. If you turned the hole right to left, it was like a speedway; you were high on the right, low on the left."

Wilson put a premium on requiring players to work the ball and control their trajectory. He liked doglegs as well as strategic, artful bunkering. Pine Valley and Merion were favorites. "A golf course should appear more vicious to the player than it actually is," Wilson told Sports Illustrated. "It should inspire you, keep you alert. If you're playing a sleepy-looking golf course, you're naturally going to fall asleep."

A third of Wilson's courses were built on the flat terrain of Florida, where he was known for building up his greens four to eight feet so golfers would have a defined target. Pine Tree, in Boynton Beach, Fla., generally regarded as Wilson's finest work, is built over a 168-acre stretch of sand and scrub pines. The layout features several doglegs and is known for its exceptional bunkering. Ben Hogan once called it, "The best course I have ever seen."

The Blue Monster's par-4 18th is Wilson's most famous hole. The closer requires two perfect shots: a tee shot that avoids water on the left and a bunker complex and trees on the right and then an approach over water into a narrow green that slopes toward the hazard. It has played as the PGA Tour's toughest hole two of the last five years.

Pete Dye has an appreciation of Wilson's work. His father, "Pinky," spent quite a bit of time playing golf with Wilson at Delray Beach in the 1930s. "After the war, there was a need for golf courses," Dye says. "Mr. Jones figured out how to get them built quickly. Dick was different. He came in wiggling with all his bunkers. It was flat in South Florida, and he would come in and build up the greens and put bunkers in front of them. Dick was a good player, and he made a strong golf course."

Rees Jones has become a student of Wilson's design elements. Along with Cog Hill, he also supervised renovations of Wilson courses at Royal Montreal and Lyford Cay Club in the Bahamas. Like Wilson, Jones also desires to have a lot of definition in his designs. The revised par-5 ninth at Cog Hill is an example, sporting a new green Jones elevated by three feet, creating a dramatic look.

Jones admires Wilson's use of tongues in the design of the greens, which provide for more strategic hole locations. He points to the par-4 seventh at Cog Hill, which has four tongues. "I don't think people could really understand his nuances," Jones says. "His bunkering doesn't look as intricate as it really is. He was very subtle. The golfer didn't even recognize why he was being challenged that way. Wilson always made sure it was a golf course you wanted to play over and over again."

As the preeminent architects of the post-World War II period, Robert Trent Jones and Wilson were fierce competitors, often up for the same jobs. A 1962 story in Sports Illustrated was headlined, "Golf's Battling Architects." Critiquing Trent Jones' work, Wilson said: "I think he gives an impression of too many straight lines. Straight lines are something you want to get away from."

"His bunkering doesn't look as intricate as it really is. He was very subtle." Rees Jones

Von Hagge recalls Wilson once was told that a prerequisite for landing a job was joining the American Society of Golf Course Architects, which Trent Jones had formed in 1946. The request had Wilson fuming. "Dick was such a competitor," von Hagge says. "He used a lot of profanity and said, 'We're not joining that bleeping union.' The real underlying tiger there was Jones was asked to put it together, and Dick wasn't. He never joined."

Architect Rocky Roquemore got to know Wilson growing up as a teenager in Georgia. His family was in the golf course business, and Wilson often was an overnight house guest. "Dick was one of the smartest people I ever knew," Roquemore says. "He was a wizard with statistics and numbers. If he told you somebody hit .308 in 1944, you could bank on it. There was hardly a subject Dick couldn't talk about intelligently. He had a good grasp of what was going on."

Von Hagge joined Wilson and Lee as a young architect in 1955. Wilson was drinking, but for three years, von Hagge says, he had a good learning experience. Then Wilson really began to drink heavily in 1958. "After that, it was hopeless," von Hagge says.

Dye has fond memories of Wilson from his time visiting Delray Beach in the 1930s. However, he had a different experience when as a young architect he spent some time with Wilson in the early '60s. "He was very volatile and unpredictable," Dye says. "One day he would give you the shirt off his back, and the next day he would throw a can of gas at you with a lighted match."

As Wilson aged and his alcohol abuse worsened, his talent often was obscured by surly or outrageous behavior. "He was so brilliant, but at the end of his life, he wasn't well," says Betty Peter, who went to work for Wilson and Lee as an artist in 1961.

Wilson was notorious for insulting and alienating contractors and their staff, especially if he had been drinking. Von Hagge remembers a violent exchange during the construction of Royal Montreal. Von Hagge was working with an excellent shaper, the person who actually molds the course with a machine. He spoke only French.

"Shapers will make and break you," von Hagge says. "Dick showed up, and he was in his cups. Dick wanted to meet the shaper. He walked over to him and said, 'You could make it or bleep it up for us. If you do, you'll never work again.'

"The kid had a smile on his face. Dick said to me, 'Tell him exactly what I said.' You could see the smile disappear. He hit Dick so hard he lost a [dental] bridge. I stopped everything, took Dick back to the hotel and got him on the next plane."

Another time, von Hagge escorted Wilson to Columbus, Ohio, for a ceremony to mark the renovation of Scioto CC. While checking in at a hotel, he noticed the crowded lobby become silent. Von Hagge turned and saw Wilson urinating in a flower pot. The breaking point for von Hagge finally occurred in December 1962. Wilson insulted von Hagge's wife, and von Hagge responded by shoving him against a wall.

"He said, 'You hit me, you hit me,' " von Hagge recalls. "He got up and swung and fell down. It was terrible."

Von Hagge quit and opened his own firm. Wilson sent messages to him, apologizing and claiming he wouldn't drink again. But von Hagge had had enough.

Despite the drinking, Wilson continued to maintain a busy schedule during his later years. Cog Hill's No. 4 course opened in 1964. There always has been question about how much of the design Wilson had done, many believing Lee did the bulk of the work. Von Hagge says Wilson was responsible for half of the design, with Lee and him accounting for the rest.

Wilson suffered a fall in a carport near Pine Tree in the summer of 1965 and died three weeks later of a pulmonary embolism. It is generally agreed by those who knew him that the years of heavy drinking finally caught up with Wilson. "Dick pretty much drank himself to death," Roquemore says.

In the subsequent years Wilson's place in history has not truly emerged like the other great architects. "He's never really gotten the credit he's due," says Rees Jones. Instead, the notoriety has been heaped on Robert Trent Jones, who was a better marketer during his much longer career.

Still, von Hagge is among those who wonder what Wilson could have accomplished if he hadn't been an alcoholic.

Could his legacy have been greater than Jones?

"I think it would have in my opinion," von Hagge says. "He would have passed Jones in reputation. Easily. Dick was innovative and bolder. Dick really would have been something."