News

Emotional Rescue

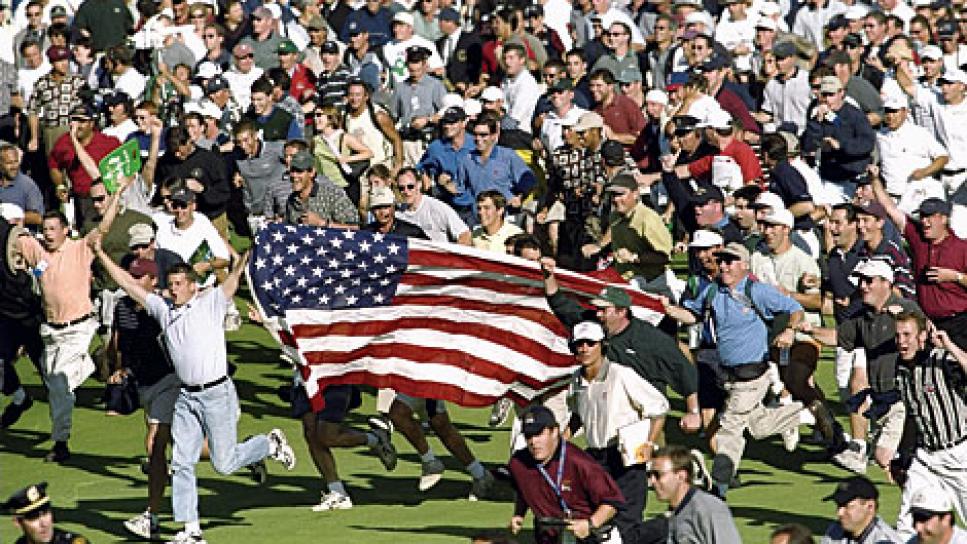

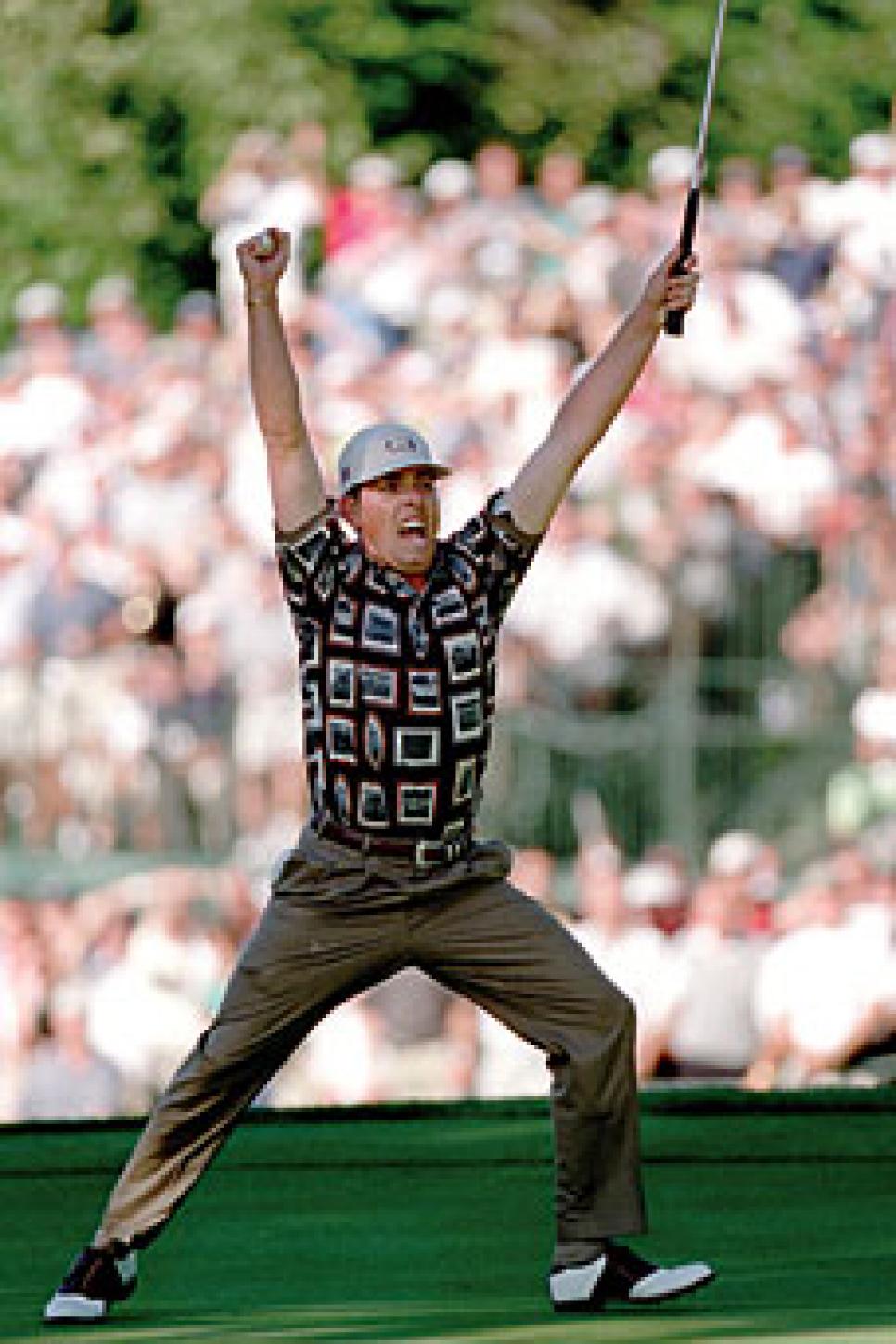

The Ryder Cup matches haven't had sustained high drama since 1999 when Leonard (bottom) led a wild American comeback.

It took the Ryder Cup 50 years to grow up, a full half-century before it matured into a competitively balanced contest worthy of considerable public interest. Now, at the sprightly age of 81, it is mired in a mid-life crisis. The last two gatherings have been frighteningly one-sided—we haven't seen a meaningful shot in the Sunday singles since Paul Azinger holed out from a greenside bunker to keep America's dim hopes alive in 2002.

In 2004 Europe routed the Yanks in such overwhelming fashion that losing skipper Hal Sutton was left shaken and disillusioned by the experience. Yes, he had thrown a couple of his players under the bus, but Ben Crenshaw had done the same thing in 1999 and his squad responded with the greatest final-day comeback in series history. Since that rally, the matches haven't sustained anything akin to high drama, and in back-to-back drubbings the Americans have been justly depicted as inferior and emotionally lackluster.

Don't think for a second that the two aren't connected. You would have to be a little weird to launch a fist pump when you're 4 down with seven to play.

Without the fervor factor, a Ryder Cup can take on silly-season insignificance. Its relevance grew exponentially from 1983 to 1995, when five of the seven outcomes remained a mystery deep into Sunday. The two that didn't became landmark victories for Europe, and on the back end of that 12-year stretch, a rapid boil of pride and passion precipitated prickly relations between the sides.

More often than not, current U.S. captain Azinger played the role of lead thorn. "It took America losing for this to become really popular," he says of the Ryder Cup's golden era. "By the War on the Shore [1991], people started freaking." Never did things get freakier than in '99, but after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks pushed the 2001 matches back a year, everyone made a conscious decision to trade in their firewood for an olive branch.

Things haven't been the same since. The housebroken version of the Ryder Cup isn't nearly as sexy. It has been neither compelling nor all that close, which makes next week's affair at Valhalla one of the more pivotal meetings in recent decades. A U.S. team without Tiger Woods will be asked to lead the revival, which, depending on one's mindset, is either an excellent excuse to lose or a great opportunity to pull off the home-soil upset.

Another European blowout, however, could greatly harm the event's mystique. It is hard to imagine the American sports fan renewing his tolerance for underachieving losers, and besides, nothing annoys the TV folks more than when a three-day duel held once every two years gets a verdict after six or seven hours. Because the Ryder Cup competes against the NFL for viewers, it rarely puts up good ratings. In a weak golf economy, this year's numbers are sure to be low.

When it comes to mainstream pull, however, the Clash For No Cash has enough value to earn the love of ESPN, which acquired coverage rights for Thursday's opening ceremonies and Friday's first round in a bizarre deal involving ABC, with whom it is a partner, and NBC, which will continue televising the weekend matches. Two years ago, ABC/ESPN was in the process of terminating its heavy commitment to the tour, ridding itself of all those lower-tier events at the end of the regular season, but the Ryder Cup is a special gathering with a unique format and substantial commercial potential.

Still, it has to live up to expectations as a product, and in the big-picture context, that requires intense suspense. It is difficult to conceive of a more powerful conclusion to any golf tournament than the gasp-for-breath finish in 1991, when Bernhard Langer stood over a six-footer for the entire shooting match and missed. Or 1995, when every singles bout seemed close and exceedingly important, when the breadth of emotions made the average Masters seem like a Merrill Lynch Shootout.

"The Ryder Cup has so much history and tradition, it's definitely a reach to say it could lose its prestige or luster," Azinger says. Maybe, maybe not. Most of that history is less than 20 years old, the stuff worth remembering, anyway. Tradition? The United States lost once between 1935 and 1983, which is why nobody gave a hoot about this series until the inclusion of continental Europe (1979). In short time, Spaniard Seve Ballesteros singlemandedly would wipe away the foreigners' inferiority complex, then do the same to the smile on Uncle Sam's face.

Enter the golden era. Better golfers than Ballesteros have walked this earth, but more influential ones? Try another planet.

The reclamation project belongs to Seve's primary antagonist. Azinger's homemade swing and fiery demeanor made him the cornerstone of several U.S. rosters, and though his 5-7-3 record hardly was spectacular, he never lost a singles match (2-0-2) or backed away from the leadership duties many of his colleagues considered a burden. More than any tour pro who teed it up for Old Glory, Azinger's career was defined by his Ryder Cup appearances. He wanted the toughest opponents, the most pressure, the biggest moment.

He's the perfect guy to lead this troop and invoke the overt intensity that has been missing on the American side, but the more you look at Azinger's team, the less you're likely to hear. Other than Phil Mickelson and perhaps Anthony Kim, this is a squad full of blend-into-the-woodwork types. A lot of nice guys, but six rookies and not a lampshade-wearer in the bunch, although Boo Weekley's down-home nature potentially could keep things loose.

At Oakland Hills four years ago, the Yanks fell so far behind so early that atmosphere was a non-factor. You can bet Azinger will send out native Kentuckians Kenny Perry and J.B. Holmes in Friday morning's first foursomes match to crank up the volume outside the ropes, and with a team with many long hitters who tend to spray their drives into galleries of any size, the U.S. skipper will make sure Valhalla's rough has little effect on one's ability to hit greens or hunt pins.

At the end of the day, however, a captain can only do so much. On paper this group of Americans is one of our weakest teams ever, then again more imposing squads have gotten hammered, and it has become fairly clear in recent years that intangibles such as chemistry and attitude mean a lot more than data and previous results. That's what made the Ryder Cup special, what made it so popular and so much fun to watch. For the health of the event itself, that's what will make this one close.