News

Five With A Flourish

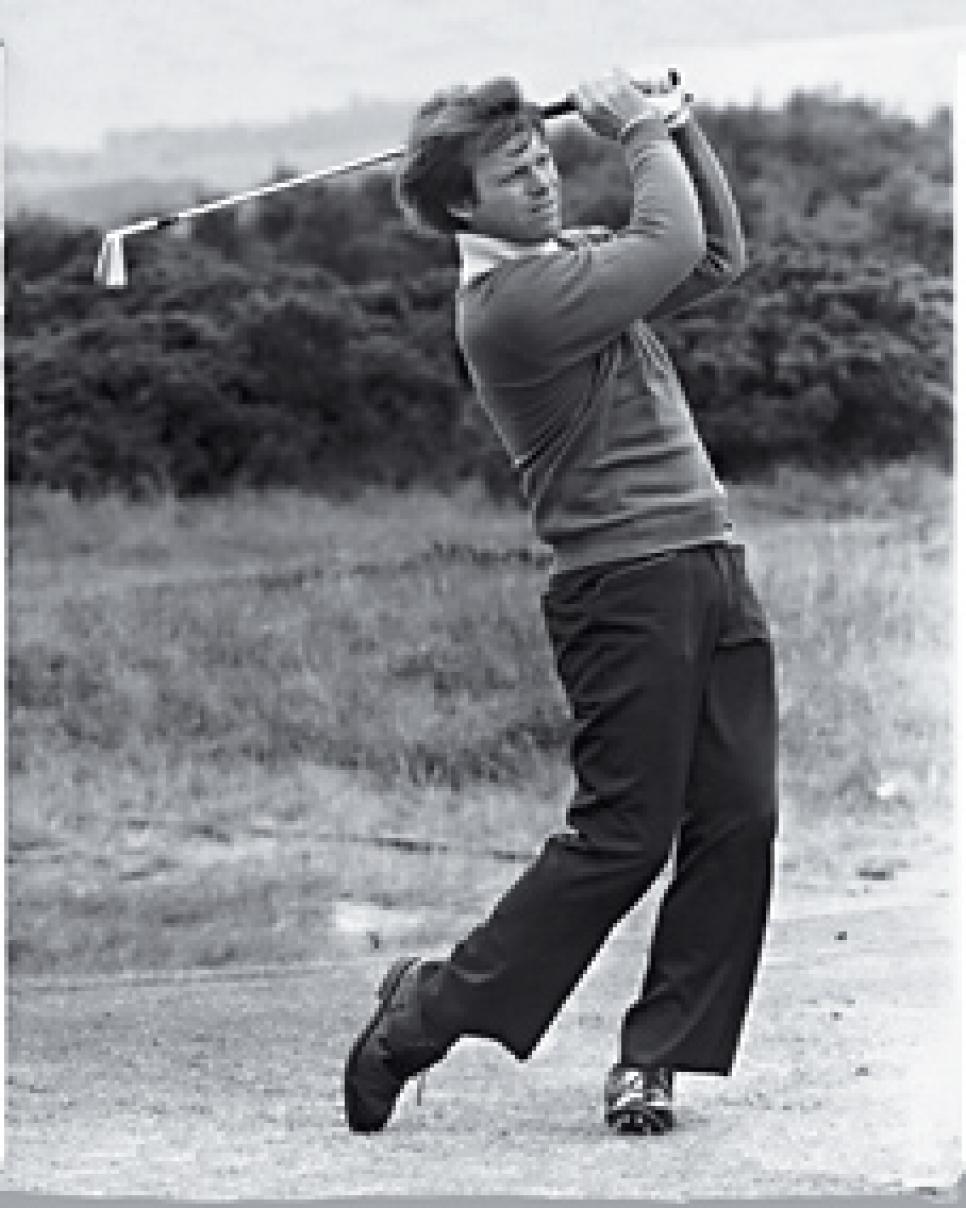

Young Tom Watson en route to Open glory in 1975

On the silver anniversary of its conclusion, Tom Watson's run of success at the British Open -- five victories between 1975 and 1983 -- remains one of the most dominant stretches in golf. Only J.H. Taylor, James Braid and Peter Thomson have claimed the claret jug as many times, and only Harry Vardon, a six-time champion, won more. Watson, though, prevailed when the fields were deeper, and he is the only man to win the event on five different courses. The passage of time makes it easier to appreciate Watson's accomplishment, and perhaps even to understand it.

Watson grew up landlocked, in the middle of America, in Kansas City, Mo., a long way from any links courses. He wasn't a noted manufacturer of shots, not a fan of the knockdown that cheats the breeze. Watson hit the ball high, which normally is no friend in the wind, but there was attitude to go with the altitude.

"I always hit it solid," he says in the matter-of-fact manner that is as much a part of his countenance as his gap-toothed smile. "I rarely mis-hit the ball." Look for other omens to explain Watson's British reign and you can find them. One of the first clubs Watson's father, Ray, put in his son's hands was a cutdown Stewart spade mashie made in St. Andrews. The Watson surname first appeared in records in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1392. The clan's motto is Imperata flourit. Translated, the motto means, "It has flourished beyond expectation."

Gritty and serious, his pace of play as brisk as his swing, Watson appeared, in his heyday and beyond, to be a self-sufficient man playing under self-induced pressure for his self-satisfaction. He owns just one replica of the claret jug, a piece of silver about half as large as the real thing. "It would be kind of neat to have five of the 90-percenters," he says. "I'm thinking about it, but they're expensive. They cost about 10 or 11 grand."

Early on, when he was just another golfer with a reverse-C swing wearing polyester slacks, Watson was concerned more with legacy than currency. "I remember one specific instance," says 1978 PGA champion John Mahaffey, who set out on tour the same time as Watson. "I won my second year in Las Vegas, at the Sahara Invitational in 1973. And Tom hadn't won yet. We were sitting in an airport in San Antonio. He just kind of looked at me and said, 'You've done something I've always wanted to do.' I said, 'What's that?' Tom said, 'You've won a PGA Tour event. You'll never be forgotten.' "

The First

WATSON WAS 25 and in Europe for the first time when he arrived at Carnoustie on the Sunday before the 1975 British Open, intent on a practice round. (The championship was played from Wednesday to Saturday at that time.) An official told him the course was open only to those who had qualified that week, so he headed to nearby Monifieth GL, not far from his rental house, to play with Mahaffey and Hubert Green.

His introduction to links golf was inauspicious, to say the least. He hit a drive off the first on the exact line his club caddie told him to take. "He said, 'Hit it right there,' and I hit it right where he told me," Watson recalls. "Couldn't find my ball. Looked for it and looked for it. I finally saw this little pot bunker, 40 yards off line from where I hit. Sure enough, it was in there. My very first shot at links golf. I said, 'This isn't golf. This is luck, or bad luck.' "

When he was able to get on Carnoustie the next day, he enjoyed the services of caddie Alfie Fyles. "It was through IMG," Watson says. "I had asked [former agent] Hughes Norton to hook me up with a caddie over there." Fyles was well known among British caddies, hailing from a large family in Southport, England, whose father had caddied at Royal Birkdale before World War I. Alfie and his brothers followed suit. Alfie's brother Albert caddied for Tom Weiskopf for many years in the British Open, including his 1973 victory at Royal Troon. Alfie worked for Gary Player at Carnoustie in 1968 when the South African won his second Open title.

"He was a hard-drinking, heavy-smoking Englishman who loved to caddie, who loved his job," Watson says of Alfie. "You don't play as much by yardage there as by feel -- what the wind is doing and what you think the ball is going to do when it bounces. I relied on him some, sure."

Watson had relied on him enough in his maiden British Open -- which he won in an 18-hole playoff over a fellow 25-year-old, Australian Jack Newton -- Fyles told Sports Illustrated's Frank Deford in 1986, that Fyles thought his pay insufficient. He said to Watson, "You must need this more than me." "Maybe there was a dispute," Watson says now. "I didn't pay very much back then, but nobody paid very much back then. I don't recall a dispute over the check. Bruce [Edwards] just wanted to caddie for me."

Without Fyles in 1976 at Birkdale, Watson missed the 54-hole cut. Fyles and Watson reunited in 1977 at Turnberry and were together for the rest of Watson's British Open triumphs. Fyles smoked the Pall Malls Watson brought him from the States; Watson listened more often than not when Fyles surmised a shot. "All you've got is your bag carriers now," Fyles told Deford. "All they can do is give the golfer a weather report -- not the right club. Once it was all eyeball." One Friday morning during their years together, Fyles reported to work with a black eye. "I joked, 'Hey, Alf, what'd you do, get in a fight last night?' " Watson says. "He said, 'Yeah, over your honor.' I said, 'Did you win the fight?' He said, 'What do you think, sir?' "

Newton and South African Bobby Cole appeared to have the tournament in hand during the final round when they got to 12 under, three clear of their closest challengers, who included Johnny Miller, Jack Nicklaus and Watson. But Watson, who was coming off demoralizing collapses in the 1974 and 1975 U.S. Opens, played solidly, making a 20-footer for birdie at the 18th to shoot 72 and finish at nine-under 279. Some Americans had trouble adjusting to slower greens in the U.K., but not Watson.

"He was so bold, it was easier for him to get locked in on the speed than a lot of other guys," says close friend Andy North. "He hit his putts so solidly and was so aggressive, [those greens] fit his putting stroke beautifully." The playoff was held on a rainy day in front of a sparse gallery as workmen disassembled the grandstands. "There were very few people following us because we were no-names," Watson says. The golf was nip-and-tuck, the outcome uncertain until No. 18 when Newton bogeyed from a greenside bunker to shoot 72 to Watson's 71.

"Sir John Carmichael, who was captain of the R&A, presented me the trophy," Watson says. "He said, 'I'd like to present the winner of the 104th Open championship, Tom … Kite.' I just smiled and took the trophy from him, and people were yelling, 'It's Tom Watson.' "

The Best

BY THE SUMMER of 1977 Watson was at the pinnacle of the sport. He topped the PGA Tour money list that season for the first of four straight years. The earlier meltdowns seemed like ancient history, especially after Watson defeated Nicklaus in a tight battle at the '77 Masters.

"It's kind of like making the second end of a one-and-one free throw when you really have to," Watson says of prevailing at Turnberry after defeating Nicklaus that spring at Augusta. "You make the first one, then you make the second one. The Masters did increase my confidence."

Watson and Nicklaus trailed Roger Maltbie by one stroke through 36 holes but, paired together for the last two rounds and each refusing to yield, turned the championship into a duel for all-time. The raucous galleries, reveling not only in the play but the unusually sunny weather, erupted in explosive roars for first one man, then the other. "It was wild," says Maltbie, who played directly behind them in the third round. "The people were running. There was a drought, and it was like we were playing into a cloud of dust all day. The cheers were remarkable."

The once and future kings matched third-round 65s. The golf was just as good in the final round. Nicklaus -- who would hit 61 greens for the week despite spraying his tee shots, compared to 51 for Watson -- built an early advantage, but Watson clawed back twice from three-stroke deficits. Trailing by two with six holes to play, Watson showed nothing but resolve. "After [winning at] Carnoustie, he had no fear of Jack whatsoever," says Maltbie. "Every era has its putter, the fellow who seems to hole the putts at all the right times, and he was certainly the guy in our era."

Watson birdied four of the last six holes, the killer a 60-footer from the fringe on the 15th. He took the lead on a two-putt birdie on the par-5 17th when Nicklaus missed a four-footer to match him. Nicklaus made a miraculous birdie from 40 feet after hitting a Herculean 9-iron from a heavy lie, but Watson answered him, easy as that, with a 7-iron to two feet to shoot a 65 to Nicklaus' 66.

"I gave you my best shot," Nicklaus said at the prize-giving, "and it just wasn't good enough. You were better. It was well played." Watson savored his best day on a golf course with the backdrop of a bagpiper playing on the lawn of the Turnberry hotel. "It was a spiritual time," he says, his voice lowering and his intense eyes softening with the memory. "When I won that Open, it solidified [my belief] that I could play with the big boys, play with the best of them. That was a dream from when I was a kid, and I worked my butt off to get there, practiced as hard as anybody. And I had some talent to go with it."

The Third

Despite winning two of the first three British Opens he entered, Watson still wasn't comfortable with links golf -- its pinball bounces, the limited value of a yardage book, even the way the shorter-than-U.S. standard flagsticks messed with his depth perception. "In particular, I didn't like St. Andrews," says Watson, who finished T-14 there in 1978. "I didn't care for all the blind shots and the bumps and such." Watson fared worse in 1979 at Royal Lytham & St. Annes, but within his T-26 finish came a revelation -- as sure as taking to warm beer and overcooked vegetables.

"I just gave myself a talking-to," Watson says. "I was really fighting myself mentally with this stuff. One particular hole at Lytham, a par 5, illuminated what had to be done on a links course. Play the bounce. The first day it played into a strong wind and I hit driver, 3-wood, 5-iron. Next day, downwind, I hit driver and then had 210 yards to the flagstick. It was an 8- or a 9-iron, and I hit the 9. Today, that's nothing. But in those days, you just didn't think about that [club] from that far away. But I hit the shot and judged it right."

His attitude suitably soothed, Watson arrived at Muirfield in 1980 having won five tournaments in the United States and overflowing with confidence. "I was putting the best I ever putted," he says. "I knew if I could stay out of the bunkers -- if I could get my ball on the greens -- I was going to make putts. And I did. I putted the absolute eyes out of the hole and made everything."

Watson, who found the sand only once all week, got off to a strong start by opening with 68 in wind and rain and secured the outcome with a third-round 64. "I played with him that round, and when we got in I couldn't believe he had beaten me by 10 shots," says Jerry Pate. "I never saw anyone hole putts like that. Tiger's putts, and Ben Crenshaw's, they go in like a rat sneaking in a hole at a carnival. They hit softer putts, and the hole just kind of swallows the ball. Tom's would be going 900 miles an hour. Often they would hit the back of the cup and pop up in the air a little and then go in."

In a final-round 69 most of Watson's putts went only one place -- to the bottom of the cup. He birdied Nos. 7, 8 and 9 to maintain control. He beat Trevino by four, with Crenshaw two strokes further back in third place. "You cannot love golf any more than you do when you come down the 18th fairway of this golf course a champion," Watson said that afternoon.

The Gift

Watson's first wife, Linda, occasionally would slip some heather into his golf bag for good luck. At Royal Troon in 1982, Bobby Clampett and Nick Price could have used a steamer trunk full of it. Watson loitered around the leader board until the two surprise contenders played themselves out and he was conveniently available to collect the claret jug for the fourth time.

Clampett, a 22-year-old devotee of the gears and levers of Homer Kelley's The Golfing Machine, who was trying to become the youngest Open champion since Willie Auchterlonie in 1893, assumed a five-stroke lead with his 67-66 start but reality settled in with a 78-77 weekend. Price, a mustachioed 25-year-old from Zimbabwe who was trying to earn his chops on the European tour, was in command deep into the final round until experiencing the kind of collapse Watson had known all too well in his first few times contending in major championships.

Coming off his dramatic conquest over Nicklaus a month earlier in the U.S. Open at Pebble Beach, Watson put up a one-under 70 in the final round playing three groups ahead of Price. The highlight was a textbook eagle 3 on the par-5 11th, the Railway Hole, where he striped a drive and then hit a 203-yard 3-iron to three feet. Watson was momentarily tied with Price, but with six holes to play on Troon's windblown, testy incoming nine, the young challenger led Watson by three.

"It was Nick's tournament," says Watson. "It was his to lose, and he lost it. But Troon has a murderous finish." Price bogeyed the 13th, carded an inelegant double bogey at the 15th and made bogey at No. 17. He tied for second place with Peter Oosterhuis one stroke behind Watson, who became just the fifth golfer (joining Bobby Jones, Gene Sarazen, Ben Hogan and Trevino) to win the U.S. and British Opens in the same year. (Tiger Woods, in 2000, would become the sixth).

The distinction of joining such elite company didn't cause much a stir within Watson. "Just winning the tournament at the present time was the only thing that mattered to me," says Watson, whose 39 wins tie him with Sarazen for 10th on the all-time PGA Tour list. "I was never one to greatly celebrate a victory. Many times, it wasn't 100 percent satisfaction. [Victories were] tainted by the fact that I didn't hit a shot I wanted to hit when I had to. I understand there is no such thing as perfect, but there is no sense in not trying to do things that way."

The Last

WATSON CAUGHT A lot of unseasonably hot weather in his British Open prime, and Royal Birkdale in 1983 was another broiling week. The players were roasting in the Prince of Wales Hotel until Linda Watson went out and purchased every electric fan she could find in Southport. The leader board sizzled, too, with names such as Trevino, Raymond Floyd, Craig Stadler, a young Nick Faldo and Hale Irwin, who was running hotter than the weather thanks to his absent-minded backhand whiff of a two-inch putt on the 14th hole of the third round.

Eight different players had a piece of the lead during the final round, which was as much a free-for-all as Turnberry had been mano a mano. In a sense Watson had turned into a vintage Nicklaus, waiting in crunch time for others to crumble and delivering the right shot at the right time to help his own cause. "I was just going along, not making any birdies or bogeys," Watson says. "It was a tough day. We had some wind. The door opened when I made a 20-footer at 16 for a birdie. I looked up at the scoreboard, and I had a one-shot lead."

Standing in the 18th fairway, still holding his slim advantage, Watson rehearsed his swing many times while waiting for the green to clear. It would be a 2-iron from 213 yards. "The ball came off hooking a little bit," Watson says, "but there was a good left-to-right crosswind. Alfie said, 'Stay there,' And I told him, 'Don't worry Alf, it'll come back.' The wind brought it back and it dropped right at the flag."

The surging spectators, allowed to scamper up the home hole, formed a curtain of intrigue for Watson. Despite the purity of the strike, he wasn't sure how long a putt he was left with until he broke through the crowd minutes later. His ball was just 15 feet from the cup, and Watson two-putting from that distance, in those days, was as sure as Secretariat down the stretch.

WATSON WAS ONLY 33 when he won at Royal Birkdale, his eighth major title, the same age Woods will be next season when he is expected to return to competition from major knee surgery. It was easy to assume there would be more British Open titles or other major glory in Watson's future. But in a scenario strikingly similar to that which plagued Arnold Palmer -- the best and boldest putter of his time, who won his final major when he was 34, and Hogan, who would freeze over putts in middle age -- Watson's putting deteriorated quickly, applying more pressure to a long game that itself was slipping as he moved into his late 30s. "He missed two of those three-footers every round," says North. "If you're giving two shots away every day, it's hard to beat anybody. I don't care how good you are, eventually it drives you nuts, or bothers you enough that you make mistakes in other ways."

Everyone is quick to put yellow police tape around the poor 2-iron approach Watson hit on the par-4 17th hole at St. Andrews in the final round of the 1984 British Open, when he narrowly lost to Seve Ballesteros. Watson also laments that moment -- "I tried to hit a heroic shot and didn't pull it off, and shoved the ball out to the right," he says -- but he was feeling the effects of what he hadn't accomplished on the greens throughout the day. "The key was how many putts I missed in the final round for birdies," Watson says. "I got the ball close a bunch of times that day and came up with nothing."

Watson's next threatened at the 1989 Open at Troon, where he shot 277 to finish two strokes out of the Mark Calcavecchia-Wayne Grady-Greg Norman playoff. "That was just smoke and mirrors," Watson says. "I had started hitting the ball crappy. Putting and ball-striking, things had just gotten away from me." In 1994, 17 years after his triumphant week at Turnberry and a few months after Fyles' death at age 66, Watson returned there hitting the ball superbly, having altered his swing at 44 for a more level shoulder turn through the ball with less tilt to his spine and the club on a more repeatable downswing plane. Despite having fought the yips, Watson, utilizing a tip from Trevino to keep his hands ahead of the ball throughout the putting stroke, shot 68-65 to take a one-shot lead into the weekend. But some doubt crept into his putting in the third round, even though a 69 left him just one back. Sunday he birdied the seventh to tie for the lead, but three-putted the eighth and ninth holes for double bogeys. He had 38 putts en route to a 74 that dropped him eight strokes behind Price, who got the Open he had fumbled away a dozen years earlier.

"I couldn't do anything with the putter the last couple of rounds in 1994," Watson says. "I could commiserate with all the people who had been out-putted by me. [It was] my most disappointing tournament ever."

WATSON HAS MISSED only three British Opens since his first one (1996, 2004 and 2007, the last for the wedding of his daughter, Meg) and, if his health permits, he plans to play in the championship through 2010 at St. Andrews, when at 60 he will be eligible for a past-champion's exemption for the last time. Being paired with Nicklaus in the Golden Bear's 2005 farewell at the Home of Golf gave Watson, who cried as Nicklaus' final round came to a close, a taste of how emotional his goodbye might be.

Still trim and athletic at 58, Watson looks a lot less like the Huck Finn character he often was compared to in his youth than a mature farmer, his deeply furrowed brow the crop of a lifetime working outdoors. A private person never eager to let too many people too close, Watson has been bothered for years by an arthritic left hip that eventually will need to be replaced, a problem he doesn't talk much about but sometimes shows in his gait late in rounds in his limited Champions Tour appearances.

"It's bone on bone," Watson says. "It doesn't hurt me walking, and I restrict the motion in my swing that can make it hurt. It just hurts me sleeping. Laying motionless, it creates pain. It's nothing I can't handle right now. When I can't deal with it, I'll have it replaced. I've been told to put it off as long as possible, and I think that's good advice."

Watson marvels at how Woods won the recent U.S. Open despite a severe leg injury. "He's tougher than I am, tougher than I was," says Watson. "He's the best who has ever played, and I've been saying it for a long time. More than anything, his attitude. One thing you can't overlook is his power. It's second to none. His ability to get the ball up and down is second to none. His skills with the putter are higher than anybody out there. If you have power and a putter -- and a great short game and imagination -- you'll find a way to get it done."

A few weeks ago in the Watson Challenge, a 54-hole stroke-play event he started in 2007 to give competitive golf in the Kansas City area a boost, Watson laughed off a cold shank on the 35th hole en route to winning. "My son, who was caddieing for me, wasn't laughing too much," Watson says, "but there was nothing I could do after I hit it except try to get the ball up and down, and I did. The thing you learn in life is, what has gone over the cliff you can't get back. You can't do anything about the luck of the bounce. You never give up. Jack was the best at it. So was Gary Player."

Never give up, never be forgotten. That, too, was a Watson motto, composed on a quintet of courses far from home, indelible for the ages.