News

Survivor

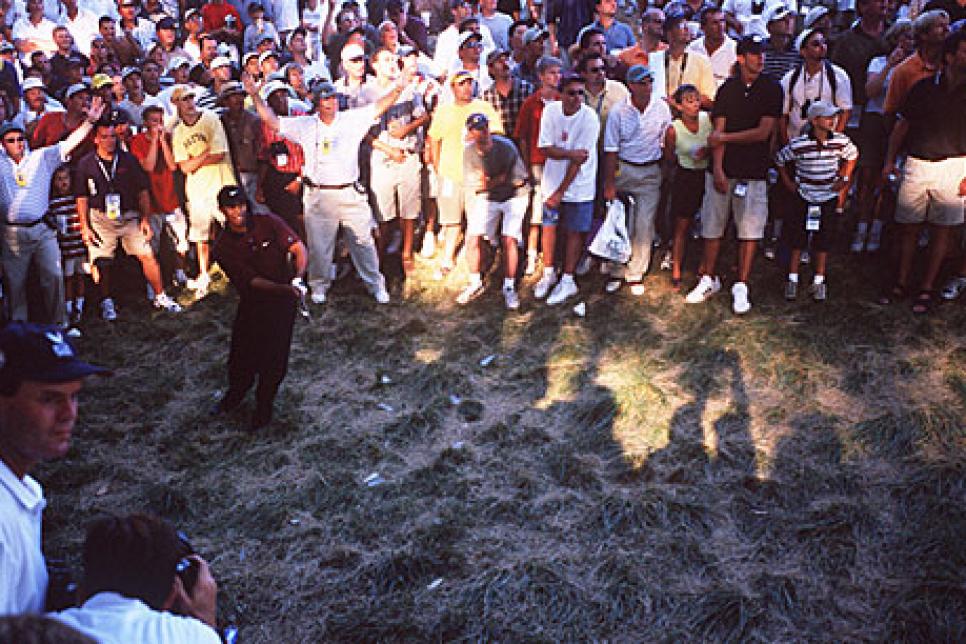

Woods' final-round recovery act included this escape on the second playoff hole.

Louisville, KY.—Back when ruling the universe was more of a goal than an occupation, Tiger Woods aspired to become the next Bob May, a 16-year-old junior golfer from Southern California whose supremacy in the region had made him something of a household name. Never mind that it was just one household. Some living rooms are a lot bigger than others.

By the age of nine, Woods had become familiar enough with May to announce that he would someday surpass all his local achievements, which turned out to be mere child's play for the kid who had already posted Jack Nicklaus' records on his bedroom wall. "He kept on saying it and doing it and saying it and doing it," May recalls of the pseudo-rivalry. "So I was hoping maybe I could get a chance to get back at him."

The opportunity presented itself last Sunday in the final round of the 82nd PGA Championship, a stage on which the roles had been diametrically altered without ever crossing. That May, a nine-year journeyman pro with a career best distinguished by four uneventful seasons in Europe, could even play his way into the final pairing with Woods seemed like (a) another indictment of Valhalla GC, the frequently maligned host venue; (b) more scathing evidence of the game's competitive vacuum; or (c) a press release from the Orange County Chamber of Commerce.

Bob May, but in all likelihood, Bob May Not. "When he [Woods] hit his tee ball off No. 1 over the trees," he said, "I knew it was going to be a different game."

A different game it was. In a duel Tiger himself called the toughest he has ever been a part of, May bent every conceivable law of logic, dumping a lifetime of grit into 21 holes before Woods claimed his third consecutive major title on a day when the gap between first and second place was as small as the last two margins were huge. "This was one memorable battle," Woods said. "It was a very special day, to have two guys competing at a level you don't see unless you have the concentration heightened to where it was."

Translation: Tiger was pushed. Pushed hard. Pushed over the edge a few times, but as was the case at the 1993 U.S. Junior Amateur and the 1996 U.S. Amateur, the 2000 Mercedes Championships and the ATT Pebble Beach National Pro-Am six weeks later, Popeye found the can of spinach right before he hit the floor. Woods played the last 15 holes in eight under. He birdied the final two holes of regulation and the first hole in the playoff, then got up and down from the Port-o-Let complex right of the 17th fairway, then won by scrambling for par after driving his ball into a spot reserved for 22-handicaps and higher.

We'll be right back after these commercial messages:

Woods becomes the first player since Ben Hogan (1953) to win three majors in one year. Not for nothing, but the Grand Slam has officially re-entered the English language as something other than a bases-loaded home run or a breakfast item at Denny's.

By finishing at 18-under 270, Woods now holds scoring records at all four major championships, setting new marks at the last three. In 2000, he played 291 holes of major championship golf in 53 under par. Twelve of his 16 rounds were in the 60s.

Woods is the youngest player to win five majors, doing it faster than Jack Nicklaus by 19 months. At the pace he has established since turning pro four years ago, Woods will break Nicklaus' record of 18 majors when he's 35, at which point he should have plenty of other things to put on his bedroom wall.

Woods is the first player to win back-to-back PGAs since 1937, when Denny Shute accomplished the feat, and the first player to do it since the PGA switched to stroke play in 1958.

Woods is the first player to beat Bob May in a playoff. Let us hope it won't be the last. "It has got to go down as one of the best duels in the game, in the major championships," said Mr. History. "Granted, there have been some great ones, but this one was up there. Both of us shoot 31 on the back nine with no bogeys. That's not too bad."

Despite growing up just 20 minutes from each other—Woods in Cypress, May in La Habra—the two had never played a competitive round together until last Sunday. And though he never won a national amateur title, May remains the youngest player ever to qualify for the Los Angeles Open—Woods also played in the tournament at the age of 16 but was given a sponsor's exemption. May went on to become a three-time All-American at Oklahoma State, including 1991 when the Cowboys won the NCAA team championship, and earned a spot on the 1991 U.S. Walker Cup squad.

In 1993, May finished fourth on the Nike Tour money list, earning his PGA Tour card for 1994. That's when he missed 24 of 31 cuts and made less than $32,000, beginning a slide that continued in Europe through 1998. But just when he appeared destined to a career in the Sam Randolph bin of tortured phenoms, May won the 1999 British Masters, finishing fifth on the European Tour in stroke average and 11th on the money list. At the age of 31, he had bought a second chance in America.

Now this. "When I was growing up in San Diego, Bob May dominated," said Phil Mickelson, who made two abbreviated runs over the weekend and finished tied for ninth. "He was a couple of years older than me, and he won every Southern California Junior Championship there was. It's just taken him a little while to get out on the PGA Tour and win, to everybody's surprise. He was one of the most difficult guys to beat head-to-head as a junior. It doesn't surprise me at all to see him going head-to-head with Tiger."

Woods' latest run at history began with another first—he and Nicklaus were paired together Thursday and Friday for the first time in competiton, a 36-hole lullaby designed to make the Golden Bear's exit from the major championship scene a memorable one. The death of Jack's mother, Helen, on Wednesday after a prolonged illness, obviously affected the occasion—Jack played terribly in the first round, took little time over his shots and looked every minute of his 60 years in the grueling Kentucky heat.

Of course, Woods performed like a man trying to win 18 majors in two days. Nicklaus' presence appeared to calm him and motivate him—there would be no club-slamming or poor decision-making with Nicklaus around. Despite missing a half-dozen birdie chances inside 15 feet, Woods roared to the top of the leader board with rounds of 66 and 67, his pursuit of a third straight major barely hindered by the collection of anonymity immediately behind him.

"He's better than I thought he was," Nicklaus said. "He doesn't have to extend himself at all to do what he is doing. I kept saying, 'I don't understand why we don't have anybody else playing that well.' Now I understand why they aren't. He is that much better."

Any advice? "I wouldn't offer any to him," Nicklaus admitted. "I'd ask him for a lesson."

Unlike the British Open, where nobody could compete with Woods, but the biggest names only the biggest names (Mickelson, Ernie Els, David Duval, Tom Lehman) did the best job of trying, last week's leader boards were a tighter bunch but frighteningly devoid of star power. Mickelson could never sustain a run. Davis Love III got to within three strokes of Woods on Saturday but quickly disappeared, finishing nine strokes back. Only José Maria Olazábal mounted any sort of threat, firing a 63 in the third round, a day that produced the lowest cumulative scoring average (71.0) in PGA Championship history.

Oakland Hills it isn't, but this version of Valhalla was considerably more worthy of a major championship than the 1996 cream puff. No less an authority than John Daly declared the Nicklaus layout "10 times better than four years ago," primarily because of design modifications and an additional 200 yards in length. The PGA's new Kentucky home could still use another set of tee boxes on several holes, particularly the par 5s, which were ridiculously easy before a Thursday night downpour softened the fairways.

"The reason scores are so low is there aren't enough driver, 4-iron holes," Lee Janzen said. "I don't think you're supposed to enjoy major championship courses, but I'd like to play here all the time. I don't know if I'd say that after a U.S. Open."

Despite a swing that appeared 10 m.p.h. faster than in the first two rounds, Woods cobbled together a 70 Saturday, taking a one-stroke lead over May and Scott Dunlap. J.P. Hayes was two back, Greg Chalmers three, meaning the four men closest to Woods after 54 holes had a combined 22 majors of experience—the same total as the 24-year-old Tiger. "It's like the pack of dogs chasing the fox," said Notah Begay III, neglecting to mention that the pack was full of chihuahuas.

For all he did to make this a terrific golf tournament, May needed to do a little more. He missed four birdie putts inside 15 feet on the front nine, then made four birdies in five holes to retain a one-stroke lead with four to play. That's when things got a little crazy. Woods missed long and left on his approach at 15; May carved a 7-iron out over the creek right of the green and stopped his ball six feet from the hole. Woods then produced his worst stroke of the day, a putt from a shaved swale that tumbled 15 feet below the hole. Tiger, you're still away.

"The one shot that meant the most to me, with everything going on, was the putt on 15," Woods would say. "If I miss and he makes, he's three up with three to go, and I'm not looking very good. To step up there and make a 15-footer with everything on the line—that's a big putt. Then he missed his on the high side and Stevie [caddie Williams] said, 'Ballgame is on now.' "

Ballgame was definitely on. May hooked his drive on 16 but roped an approach out of the rough, around a tree and onto the green, salvaging a par. Woods obliterated his drive on 17, pumped a lob wedge to four feet below the hole and converted to regain a share of the lead. Then, after both men hit the par-5 18th in two, May blasted a 70-foot putt that rumbled 15 feet past the hole. Woods responded by rolling his eagle attempt six feet long.

At this point, it appeared Bob May Not after all. "Actually, I was playing it outside-left, and it started breaking back across the hole," May said. "I don't know if it was coming back [left] or not, but as slow as it was going, I think it was just taking tracks of footprints or whatever. It just happened to catch the right side of the hole."

May's birdie forced Woods to make the six-footer to force extra holes, and Tiger did what he always does, sneaking it in the side left door and kicking off the first three-hole, British Open-style playoff in PGA history. At this point, it's safe to say Woods was a little juiced. After May duck-hooked his drive and slapped his approach 50 yards short of the 16th green, Tiger nuked a 7-iron from 196 yards, stopping it 20 feet right of the flag. May chopped his third from the hay, rolled it across the length of the green and almost holed out.

Woods tried not to laugh. Then he ran after his 20-footer as it tumbled into the cup, plucked it out of the hole and danced off to the 17th.

The final two holes offered classic examples of champion's luck. Woods' escape from the Port-o-Lets probably never would have made it to the swale behind the green had it not skimmed off the cart path. On 18, his drive could easily have sailed out of bounds or richocheted into a bush, which it appeared to do before mysteriously shooting back down the cart path and into an open space. As it turned out, Woods hit three poor shots on the final hole and still tapped in for par.

Bob May Not have his major championship, but he did have his day in the sun, restoring competitive law and order to a game that still appears endangered by the greatness of a single human being. Woods wins big, Woods wins small. Woods likes to win. Woods wins them all.

"That was a pretty good comeback," he said, comparing this victory to the amazing rally against Steve Scott in the 1996 U.S. Amateur, "but today was probably more special. Just because of the fact that we both played well at the same time. Steve Scott played well in the morning and all right in the afternoon. I played terrible in the morning and great in the afternoon. We never really timed it so that we were both playing at a high level at the same time.

"This was a different story."

Actually, it was a delightful new twist to an old one.