Instruction

The Feel of a Good Shot

During one of my regular games at Latrobe Country Club this past summer, I suddenly started putting better than I have in 25 years. My touch on the greens, which I thought had disappeared forever, came back in an almost magical way. Now I'm making them from everywhere with that wristy old stroke of mine, and I love that I'm shooting some pretty good scores and winning a lot of bets. But a part of me also wonders, *Why couldn't I have putted like this during my career on the Champions Tour? *All I can do is smile and shake my head.

Feel is the most perplexing part of golf, and probably the most important. Beginning in the mid-1960s, my touch would mysteriously leave me, especially with my putter, and I'd be left wondering when it would return. It always did come back, but in the meantime I tried all kinds of experiments to help things along. Somebody told me drinking hard liquor was bad, so during tournaments I stopped having a cocktail with dinner and switched to having a beer. That only made my touch worse, because the extra calories made my hands feel puffy. Next came a tip I'd heard from Ben Hogan: Drink ginger ale every day. That one actually seemed to work, probably because ginger ale has a diuretic property that drains you of excess fluid and can make your hands feel wiry. Another thing that helped me was lots of sleep. I rarely had good feel the day after I'd gotten to bed late, or tossed and turned all night.

At one point I decided to read up on what others had to say about feel. The results weren't helpful. Instructors don't seem to understand it very well. In fact, great touch is often written off simply as "talent," which is crucial, because a good swing can take a golfer only so far. I've seen thousands of fantastic swings in my day, but that doesn't guarantee anything. What sets outstanding players apart is the ability to vary the speed of the clubhead a couple of miles an hour, to time the release and adjust the swing path and clubface a degree or two to hit little draws and fades and alter the trajectory. To me, that's feel. But how do you teach that?

Then there's the short game, where feel comes into play even more. I realize that greens are faster and firmer these days, and greenside rough is denser, which places a great emphasis on touch. But course conditions in the 1950s and '60s were problematic in their own way. Bunkers and the grass around the greens were inconsistent, and you needed great feel to judge how the ball would behave on chips and pitches. Raymond Floyd was the best I ever saw at that. The greens we played on tour were often slow and inconsistent, and you really had to whack the ball to get it to the hole. That's why I, along with many other players, developed a wristy stroke. When my touch was good, that handsy method worked great. But as greens got faster, it just didn't work as well.

My search for ways to improve my touch has never ended. We players tried a lot of different things and compared notes. Little fads would set in. For a while, a number of fellows tried soaking their hands in hot water before they went out to play. That helped some, especially in cold weather, but of course our hands would get cold after a couple of holes. That led to the next fad: those primitive hand warmers that worked by igniting a stick of fuel inside a steel case. But they were cumbersome and tended to overheat. Next came emery boards, borrowed from our wives and used to sand down our calluses and make our hands more sensitive.

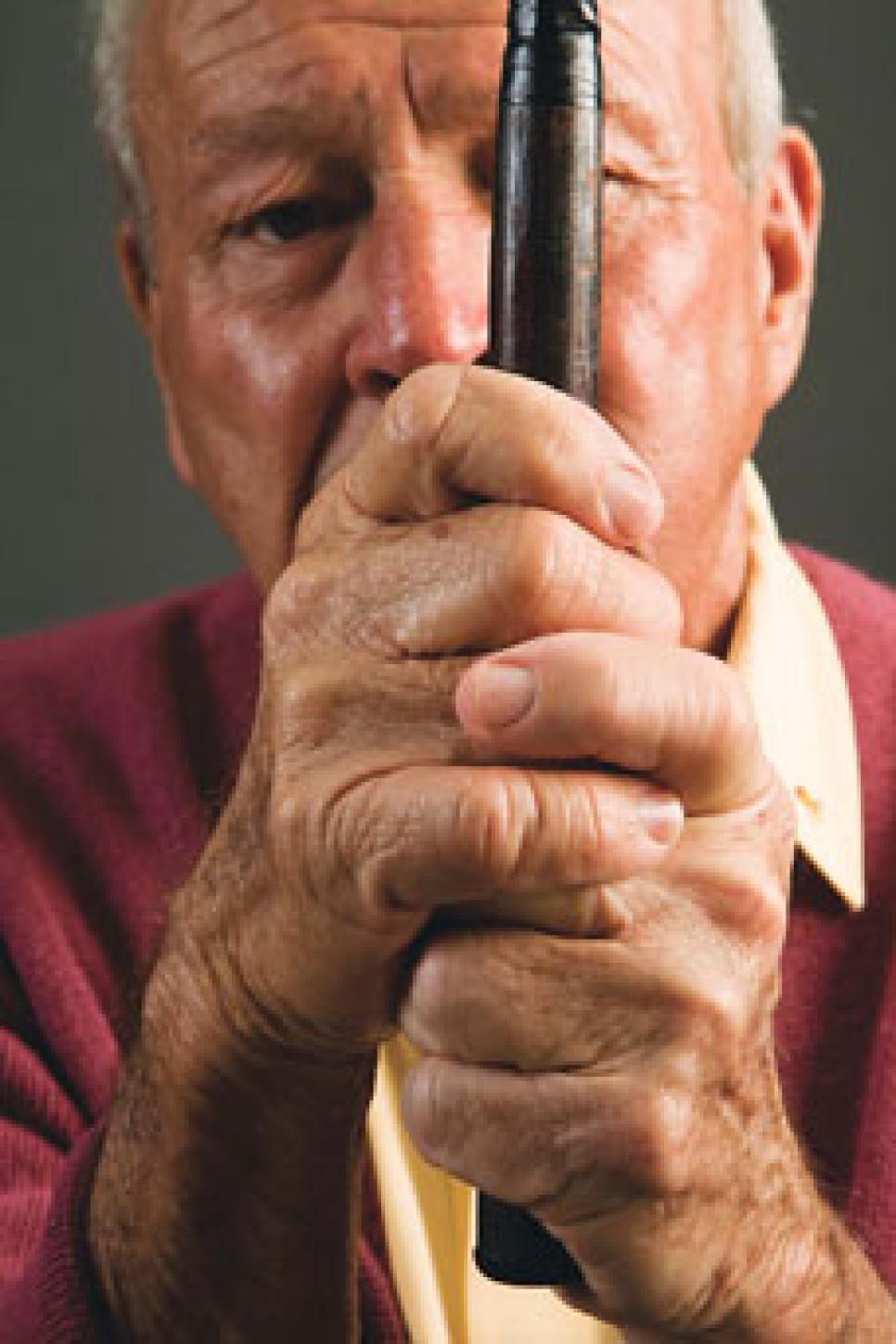

We really fooled with our putters a lot, too, moving lead tape or solder around, shortening and lengthening, tinkering with grips and so on. The putting grip I'm demonstrating in these photos is known today as the double-reverse overlap. I'm proud of that grip, because as far as I know, I invented it for putting. From the time I started using it, in the mid-1950s, it has always seemed to knit my hands together just right. As for the skinny putter with the slip-on leather grip I'm holding, I built that myself around 1955. With that putter and subsequent models, I did all kinds of things to promote feel, including running the wire from a coat hanger under the grip to serve as a reminder where my thumbs should go. The thumbs, incidentally, are a bigger source of feel than the fingers. I also used hacksaw blades under my putter grips for a while. They were nice and flat, and just the right width. This goes to show how hard players will look for the secret that'll lock in their feel.

Photo By Walter Iooss Jr.

My sense of feel came a bit by accident. When my father handed me my first club, when I was 3, he showed me the proper grip and said, "Don't you ever change that!" I'm sure Pap wanted me to have a grip that worked from a mechanical standpoint, but the way he set my hands on that club also gave me great sensitivity. I never tried to grip the club lightly. Sam Snead told me on more than one occasion I should hold it like I was holding a baby bird, but I never went along with that. I think a firm grip helps you control the club and prevents it from turning in your hands. Another thing about feel is, if you make a change in your grip, it takes time for your brain to adapt. My left-hand position got too strong when I was a teenager at Wake Forest, which some-times caused a hook, so I weakened it and vowed to play through the change. I still have that weak left-hand grip today, though my right hand is what you'd call neutral. It helps that I have very large hands, although my hands aren't as large as Byron Nelson's -- he had the biggest hands for a great player I ever saw. I'm not tall, but my glove size is extra large.

The material used for the grip itself is important, too. I always liked leather grips and still do, because I don't like the vibration that comes up the shaft at impact to be dampened too much. Jack Nicklaus feels the same way. But I'm trying rubber more often, and I suppose I'm getting used to it.

So, the search goes on. Right now I'm feeling, at age 79, like I'm one of those rare guys who discovers more feel the older he gets. But I wouldn't be surprised if it suddenly left me. As my friend Gary Player says, "Golf is a puzzle without an answer."