Courses

Trump World

In April, I traveled to northeastern Scotland to visit Donald Trump's newest golf course, Trump International Golf Links, which was nearing completion. (It's scheduled to open a week before the Open Championship, on July 10.) The site is a 2½-hour drive north from the Old Course at St. Andrews and about 10 miles beyond the port city of Aberdeen. From the A90--a two-lane road that roughly parallels the North Sea coast between Carnoustie and Fraserburgh--I could see marram-grass-covered dunes in approximately the right location, just past the village of Balmedie, but I couldn't figure out how to get to them from the highway. In the end, I followed an enormous truck, which was carrying a load of crushed stone, down a muddy one-lane "works" road--the sort of road you wouldn't go near unless you were driving a stone-filled truck or a rental car. I spun my tires in axle-deep ruts, backed up near a long trench that was being excavated for water pipes, and, finally, spotted three other cars, which had been parked near a construction fence. On the far side of the fence, two workmen were carrying a ladder around the corner of an old stone building--which turned out to be the Scotland headquarters of the Trump Organization.

The project began in 2006, when Trump paid a little more than $11 million for most of the Menie Estate, a baronial property dating to the 14th century, and, with characteristic bravado, announced his intention to build "the greatest golf course anywhere in the world." The proposed site was in the middle of a mini-mountain range of coastal dunes, on linksland that was protected by a highly restrictive conservation designation. A local planning council turned down Trump's application, by one vote, but the Scottish government intervened, citing likely economic benefits, and Trump won permission to build two courses, a clubhouse, a 450-room hotel, 950 vacation houses and 500 residences, among other amenities. Construction of the (first) course began in 2010. At its peak, it involved more than 200 workers, some of whom labored through the night, under lights.

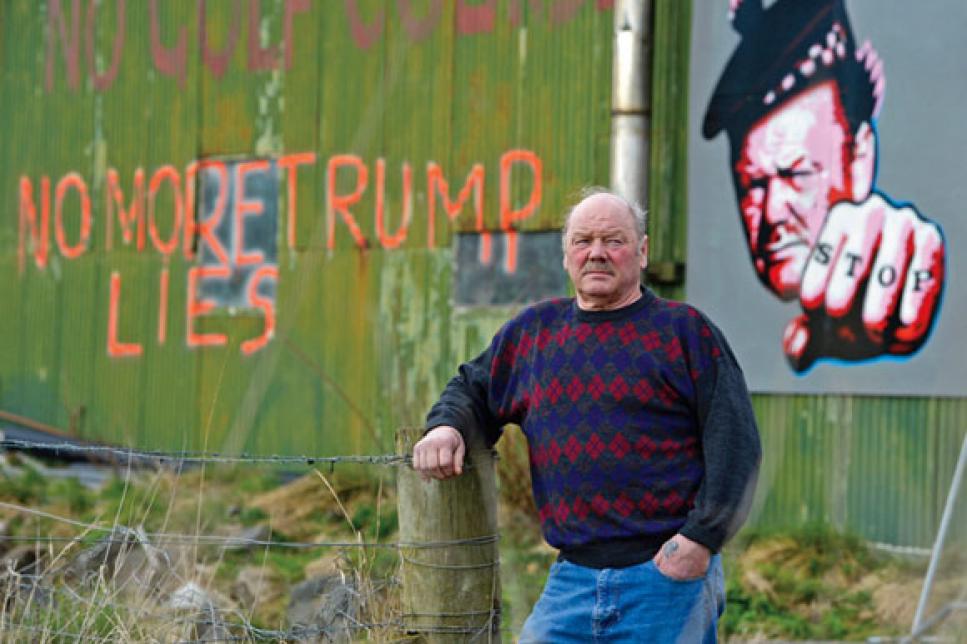

As has often been the case recently, Trump's name and picture were all over the news at the time of my visit. He had lashed out at Alex Salmond, the head of the Scottish government--a surprising target, because Salmond, whose title is First Minister, was largely responsible for the reversal of Trump's initial planning denial. Trump was furious at him now, however, because Salmond's government wanted to erect 11 offshore wind turbines in Aberdeen Bay, and in clear weather the turbines would be visible from parts of the Menie Estate. A Trump spokesman, the day before, had accused Salmond of "putting Scotland in dangerous territory by destroying some of its most pristine natural assets"--pretty much the same argument that Trump's antagonists had been making against him.

The parameters of Trump's outrage on almost any subject are impossible to measure precisely. He thinks renewable energy is left-wing baloney, of course, and he is sensitive, as a real-estate man, to the value of unimpeded water views. But he also clearly shares P.T. Barnum's conviction that any publicity is good publicity. During his project's early stages, he pursued a bitterly vituperative public battle with an adjacent property owner, and in 2011 that battle provided the narrative spine of a scathing Scottish documentary, titled "You've Been Trumped," which, if its subject had been you, might have turned your mother against you. Yet the confrontation, perversely, has probably helped him, by increasing awareness of his project among golfers all over the world: brand-building, Trump-style.

People who have had less long-term exposure to Trump than most Americans don't necessarily know what to make of him. His mother was born in Tong, on the northernmost island in the Outer Hebrides, but he strikes most Scots as purely American, and not in the good way. The ones I talked to--on golf courses, in pubs and elsewhere--seemed to think of him as a standard-issue greed-driven mega-mogul, rather than seeing him the way I think most of his countrymen do, as the only conceivable member of whatever category he actually belongs in. The Scots do, however, share our baffled fascination with his hair--a subject about which they might, by now, know more than we do, because Scottish coastal winds can make it do tricks we've never seen at home.

When it was time for Trump to choose an architect for his course, he followed the advice of Peter Dawson, the chief executive of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews, and hired the English links-course specialist Martin Hawtree. Hawtree is taciturn and professorial--qualities that have never been attributed, even by accident, to his client--yet by all accounts he and Trump get along extremely well. One of many Trumpian mysteries, to those who know him only from television and Scottish documentaries, is that people who work closely with him tend to like him, and often to like him a lot.

One such person is John Bambury, who is Trump's course superintendent. Bambury is Irish. He joined the project in April 2011 as its "grow-in" specialist, charged with establishing the fairways, greens and other turf areas. He told me that he'd assumed, before he began, that he'd do the job and move on, in the nature of his profession, but that he had been "blown away" by the Menie property. "I was here 20 minutes," he said, "and I told myself, This is it."

Bambury is in his mid-30s. He has piercing gray eyes, and I sometimes had to scramble to keep up with him as we walked the course, beginning on the first tee and ending on the 18th green. He said that Trump's principal instruction to him had been to make the fairways tee quality, the tees green quality, and the greens the best in Scotland. That was a huge challenge, he said, but also an appealing one, given that Trump had the money to make it feasible. The green surrounds were sodded with the same turf as the greens--more than 10½ acres' worth in all.

There are several methods for creating a links course. One is the way it was done in Old Tom Morris' day, when golf holes were more nearly discovered than designed, and turf preparation and maintenance were often performed by cattle and sheep. Twenty-first-century versions of the same approach are still possible. In late April, I played a round at Carne Golf Links, in Belmullet, Ireland--one of my favorite courses anywhere. That club, over the past few years, has been creating a (stunning) third nine, in large part by strategically mowing the beach grass in selected valleys among the dunes. Repeated mowing helps native fescues to displace coarser grasses--the same effect that grazing has--and if you keep at it long enough you end up with fairways. A vastly more interventionist approach is the one that was employed by the American architect Kyle Phillips at Kingsbarns Golf Club, just outside St. Andrews. There, Phillips created what is essentially a brilliant imitation of a links course, by carving dunes and mounds and plateaus and swales from a large parcel of topographically featureless farmland.

Hawtree, on the Menie property, has done some of both. He took advantage of links serendipity, by allowing the existing dunes to dictate much of the routing and many of the major elements of his design, but he also did some very serious earth-moving--something that's easy to do in sand. On the third hole, which can measure anywhere from 108 to 205 yards, depending on which of the five tee positions a player chooses, the contours in the green complex appear natural but are pure Hawtree, Bambury told me. In parts of the course, he said, workers lifted the covering vegetation and then replaced it after the underlying sand had been reconfigured to suit Hawtree's specifications.

Trump has high ambitions for the course: His dream is to someday host a British Open or, at any rate, a Ryder Cup. The course has several features that make it at least plausible as a modern major-tournament venue: a designer anointed by the R jaw-dropping length from the most extreme tees (more than 7,400 yards); and a full complement of big-event infrastructure, including a vast driving range, a 3,000-square-meter practice putting green, a network of service roads and pathways that are mostly concealed within the course, and ample room for spectators and their cars.

When Trump began, many critics took it for granted that he would build an American-style course--like, say, the Centenary Course at Gleneagles, in central Scotland, which was designed by Jack Nicklaus and is filigreed with paved cartpaths. (The Ryder Cup Matches will be played at Centenary in 2014, the latest example of Ryder Cup Ltd.'s apparent determination to ignore the golf history of the British Isles. The three best new courses in Scotland--Trump International, Kingsbarns and Castle Stuart, five miles east of Inverness--were developed by Americans.) "People assumed that he wouldn't understand links golf, but he does," Bambury told me, as we stood on the tee of the 13th hole, a tremendous par 3, which plays straight toward the sea and an Alps-like cluster of dunes. The course is fully worthy of its magnificent setting, and, unlike Centenary, is walking only: no golf carts allowed. And, despite its length from the farthest tees and the visual separation of most of the holes from one another, it's definitely walkable: The distances between greens and tees are almost all short, and players who choose tee markers appropriate to their handicaps (and to the day's average wind speed) should have no more trouble than they ought to.

FROM SCOTLAND TO PALM BEACH

When I pulled up in front of the clubhouse at Trump International Golf Club in West Palm Beach--Trump's courses, like his buildings, are easy to alphabetize--a parking valet, who was dressed in white trousers, a white shirt and a white cap, stepped briskly toward my rental car. I popped my trunk, opened the door and then--with a possibly audible gasp--realized that the valet wasn't a valet, but was Trump himself, who had come out to the curb to greet me. I (deftly concealed the folded five-dollar bill I'd slipped out of my wallet and) enthusiastically shook his hand.

Trump has a seemingly boundless ego, which he props up in the usual way. (The typeface on his Adopt-a-Highway sign on the West Side Highway, in Manhattan, is large enough to be read from Weehawken.) In person, though, he can be extremely kind and engaging--even if you assume, as you often should, that he has something up his sleeve. The night before our golf date in Florida, he called my wife, back home in Connecticut, to make sure I was still coming, and then chatted amiably with her and invited her to fly down, too. The call had a subtext, because he was undoubtedly hoping I'd write nice things about him; but my wife enjoyed talking to him, and he made the call himself.

Inside his clubhouse, he introduced me to various distinguished members and guests, including Raymond Floyd (who was leading an outing of business executives); the New England Patriots' head coach, Bill Belichick, and his girlfriend, Linda Holliday; the CEOs of AT&T, NASDAQ, Macy's and several other corporations; a man he referred to as "the richest guy in Germany"; and, in the locker room, the crooner Vic Damone. False modesty--much less actual modesty--is not among Trump's vices. "These guys run America," he said as we walked down a hallway. "We have the big people here, in terms of membership. Everybody who's anybody in Palm Beach is a member here. So, anyway. ..." (When I left, that afternoon, the parking spaces nearest the main entrance were occupied by Ferraris, Bentleys, Porsches, a Lamborghini, a Rolls-Royce and several of the really expensive kind of Mercedes--a decorative, non-random lot sampling requested by the boss, I assumed.)

One appealing thing about hanging around with Trump is that you don't have to worry about embarrassing yourself by doing something crass. You can wear your golf hat indoors, answer your cellphone if it rings and ask what anything costs--assuming he hasn't told you already. He's also fun to play golf with, and, despite occasional claims to the contrary, he's a player. He has won the club championship at Trump International three times--most recently, a caddie told me, after a final match against a technically superior golfer, who lost despite almost never missing a fairway or a green. Trump hits his driver very well, and he's a good ball-striker. His wedge game is poor (although he chipped in twice during our round), but he compensates by being an almost ridiculously good putter, especially on putts that matter.

That night, I stayed as Trump's guest at the Mar-a-Lago Club, a few minutes' drive from the golf course. The word "estate" doesn't begin to describe Mar-a-Lago. It was built in the 1920s by Marjorie Merriweather Post, the rich-beyond-reckoning breakfast-cereal heiress, whose second husband (of four) was E.F. Hutton. She used it for just a few weeks each year, as a winter retreat for herself and her friends, and when she died, in 1973, she left it to the United States as a potential sanctuary for presidents. Maintaining Mar-a-Lago turned out to be too costly for a mere country, and Trump bought it in a distress sale in 1985. The deal included a pre-negotiated agreement to tear the place down, and the first check Trump wrote after the closing, he told me, was to buy out the contract of the demolition company. Since then, he has made major additions, in keeping with the original structures, while preserving the extraordinary core of the main house. He now runs Mar-a-Lago as a private club. Michael Jackson and Lisa Marie Presley spent their honeymoon there, in 1994; the next occupant of my suite, the young woman at the front desk told me, was going to be Bill Clinton. (I told her I'd sleep on top of the bedspread.)

Over dinner that evening, Trump and I talked mainly about his golf properties. In 2004, he turned the former Bedminster, N.J., estate of John DeLorean (the disgraced automobile executive, who died in 2005) into Trump National Golf Club, and this spring the United States Golf Association selected the course, which was designed by Tom Fazio, as the site of the 2017 U.S. Women's Open.

In recent years, Trump has made a specialty of buying, renovating and profitably resuscitating bankrupt or struggling golf clubs--among them, most notably, Ocean Trails, in Rancho Palos Verdes, Calif. (now Trump National Golf Club Los Angeles); Pine Hill, in southwestern New Jersey (now Trump National Golf Club Philadelphia); and, most recently, the Doral Golf Resort & Spa, in Miami (still Doral, at least for now). He paid far less for all three properties than their previous owners had pumped into them--but, he told me, his investments weren't dictated by bargain prices alone.

"Palm Beach is the richest place anywhere on the planet, in terms of, you know, wealth," he explained. "And yet it takes me four minutes to get to my course from Mar-a-Lago. That's called location. The course was designed by Jim Fazio [Tom's brother], and it's considered the best one in Florida, but even if it were terrible it would be a big success, because of where it is. We have members who are also members of Seminole, and members of other clubs, but they come to my course because it's so close. People will hire Tom Fazio, or they'll hire Gil Hanse, and they'll build a good course--but if they build it in a lousy location it can't work."

As we were eating dessert, two giggling little girls approached our table from across the terrace, and, still giggling, introduced themselves to Trump. (They were part of a group from Bedminster.) Trump talked with them for a while, then asked them if they hoped to become supermodels when they grew up. They said that they did.

HOPING TO ENHANCE A CLUSTER OF GOLF

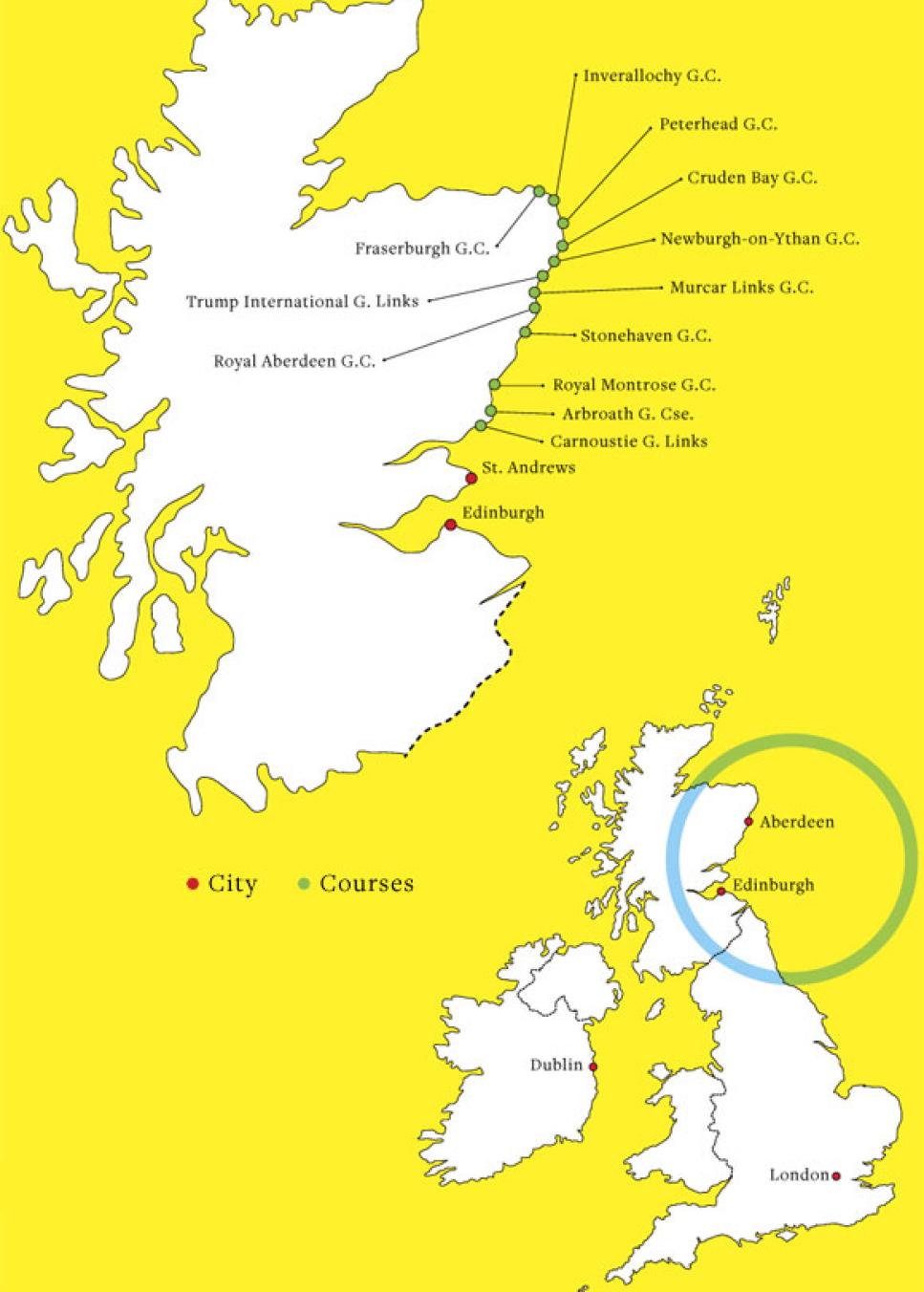

Location is a major issue for Trump in Scotland as well, but in more complicated ways. His course is ideally situated in one sense, because it sits on prime links-land in the country where golf began. Yet the location is also potentially problematic, because Balmedie is farther up the coast than American golfers and other visitors have generally been accustomed to travel. Royal Aberdeen (a few miles south of Trump's course) and Cruden Bay (a half-hour north) are among the best courses in the country, and they have many international fans, including me, but links-golf pilgrims who venture north from the Old Course often turn around after playing Carnoustie, a good hour and 20 minutes to the south.

Golf courses, hotels and other businesses throughout the country have suffered, in recent years, from a general decline in tourism and business travel, and many residents of Aberdeenshire and Angus (and the Scottish parliament) believe that a successful Trump venture could increase the appeal of the entire region as a destination. Among his most enthusiastic supporters has been Stewart Spence, the owner of The Marcliffe Hotel and Spa, in Aberdeen, who displays photographs of Trump's course in an album in the lobby. (The Marcliffe is terrific, by the way. It's a type of establishment that my traveling golf buddies and I are of two minds about: A Place You Could Take Your Wife.)

Golfers who do allow Trump to lure them north will be rewarded--and not just by his course, because the Scots have been playing golf among the dunes along that coast for centuries. The course at Royal Montrose, a half-hour north of Carnoustie, is celebrating its 450th anniversary this year. Five miles south of Trump's course is Murcar Links Golf Club, where the Scottish Boys Championship was played this spring. Murcar directly abuts Royal Aberdeen (host of the 2011 Walker Cup), and visitors to each course sometimes accidentally play onto the other, as I nearly did. And roughly the same distance north of Trump's course is Newburgh-on-Ythan, where I played with two other Daves, both of whom were retired employees of BP, which has been a bulwark of the regional economy for decades. Newburgh's 18th hole is an excellent par 5, which (before someone improved it by softening the radical curve of its original fairway) was said to be the longest hole in Scotland, at something more than 600 yards.

Forty-five minutes north of Trump's course--and a half-hour beyond Cruden Bay--is Peterhead Golf Club, on Craigewan Links. Its first three holes were created in 1969, when the threat of erosion led the club to abandon three holes closer to the sea. Less than 20 miles farther along is Fraserburgh Golf Club, which was established in 1777 and is probably my second favorite, after Cruden Bay, among the courses up the coast from Carnoustie. Fraserburgh's first and 18th holes are flat and forgettable, but nearly everything in between is brilliant.

Virtually next door to Fraserburgh is Inverallochy Golf Club, which is the home course of First Minister Alex Salmond, Trump's parliamentary benefactor-cum-nemesis. In 1905, Inverallochy's 10 best players, all fishermen, traveled to Sandwich, England, to play a 36-hole challenge match against Arthur Balfour, the British Prime Minister, and nine members of Parliament. The fishermen lost. After my round at Inverallochy, I drank a cup of coffee in the clubhouse with John R. Whyte, whose grandfather played on the defeated side. "My mother used to say that the fishermen lost because their jerseys were too tight," he told me. (An alternative explanation, offered on the the club's website, is that the fishermen themselves were too tight, owing to a largely liquid lunch.) In 2005, Salmond assembled a team of British and Scottish Parliament members for a rematch, at Inverallochy--which the local players, among them Whyte, won convincingly, thereby leaving the competition tied, after a century, at one-all.

Trump has sometimes threatened to abandon the rest of his development plan, including the hotel and the vacation houses, if wind turbines go up along what he now thinks of as his coast. His longing to host a big tournament might make it emotionally impossible for him to carry out that threat, although with Trump you never know. Perhaps he could settle his differences with Salmond on the Inverallochy model, over 36 holes on a neutral course--say, Royal Aberdeen. No matter what happens, though, golfers can rest easy, because his course is in, and there are lots of other places to stay.

HERE'S A TRIP TO CONSIDER AFTER A VISIT TO ST. ANDREWS

Donald Trump's new Trump International Golf Links will give golf travelers another reason to push farther north than Carnoustie after visiting the Old Course at St. Andrews. Royal Aberdeen and Cruden Bay have been known as top attractions, but a number of other courses in the area have been host to games among the dunes for hundreds of years--in Royal Montrose's case, 450 years.